A hernia is the abnormal exit of tissue or an organ, such as the bowel, through the wall of the cavity in which it normally resides. The term is also used for the normal development of the intestinal tract, referring to the retraction of the intestine from the extra-embryonal navel coelom into the abdomen in the healthy embryo at about 7½ weeks. Various types of hernias can occur, most commonly involving the abdomen, and specifically the groin. Groin hernias are most commonly inguinal hernias but may also be femoral hernias. Other types of hernias include hiatus, incisional, and umbilical hernias. Symptoms are present in about 66% of people with groin hernias. This may include pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen, especially with coughing, exercise, or urinating or defecating. Often, it gets worse throughout the day and improves when lying down. A bulge may appear at the site of hernia, that becomes larger when bending down. Groin hernias occur more often on the right than left side. The main concern is bowel strangulation, where the blood supply to part of the bowel is blocked. This usually produces severe pain and tenderness in the area. Hiatus, or hiatal hernias often result in heartburn but may also cause chest pain or pain while eating.

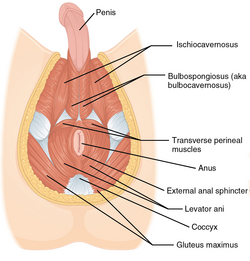

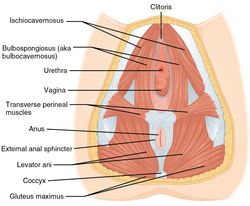

The perineum in humans is the space between the anus and scrotum in the male, or between the anus and the vulva in the female. The perineum is the region of the body between the pubic symphysis and the coccyx, including the perineal body and surrounding structures. The perineal raphe is visible and pronounced to varying degrees. The perineum is an erogenous zone. This area is also known as the taint or chode in American slang.

The levator ani is a broad, thin muscle group, situated on either side of the pelvis. It is formed from three muscle components: the pubococcygeus, the iliococcygeus, and the puborectalis.

The coccyx, commonly referred to as the tailbone, is the final segment of the vertebral column in all apes, and analogous structures in certain other mammals such as horses. In tailless primates since Nacholapithecus, the coccyx is the remnant of a vestigial tail. In animals with bony tails, it is known as tailhead or dock, in bird anatomy as tailfan. It comprises three to five separate or fused coccygeal vertebrae below the sacrum, attached to the sacrum by a fibrocartilaginous joint, the sacrococcygeal symphysis, which permits limited movement between the sacrum and the coccyx.

A rectal prolapse occurs when walls of the rectum have prolapsed to such a degree that they protrude out of the anus and are visible outside the body. However, most researchers agree that there are 3 to 5 different types of rectal prolapse, depending on whether the prolapsed section is visible externally, and whether the full or only partial thickness of the rectal wall is involved.

The pelvic floor or pelvic diaphragm is an anatomical location in the human body, which has an important role in urinary and anal continence, sexual function and support of the pelvic organs. The pelvic floor includes muscles, both skeletal and smooth, ligaments and fascia. and separates between the pelvic cavity from above, and the perineum from below. It is formed by the levator ani muscle and coccygeus muscle, and associated connective tissue.

In gynecology, a rectocele or posterior vaginal wall prolapse results when the rectum bulges (herniates) into the vagina. Two common causes of this defect are childbirth and hysterectomy. Rectocele also tends to occur with other forms of pelvic organ prolapse, such as enterocele, sigmoidocele and cystocele.

An abdomino perineal resection, formally known as abdominoperineal resection of the rectum and abdominoperineal excision of the rectum is a surgery for rectal cancer or anal cancer. It is frequently abbreviated as AP resection, APR and APER.

Pelvic exenteration is a radical surgical treatment that removes all organs from a person's pelvic cavity. It is used to treat certain advanced or recurrent cancers. The urinary bladder, urethra, rectum, and anus are removed. In women, the vagina, cervix, uterus, Fallopian tubes, ovaries and, in some cases, the vulva are removed. In men, the prostate is removed. The procedure leaves the person with a permanent colostomy and urinary diversion.

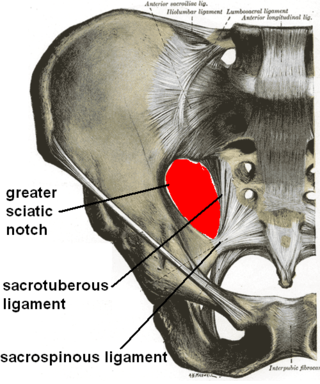

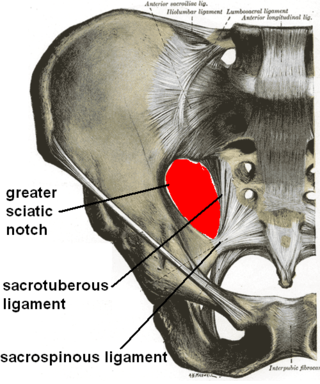

The sacrotuberous ligament is situated at the lower and back part of the pelvis. It is flat, and triangular in form; narrower in the middle than at the ends.

The anal triangle is the posterior part of the perineum. It contains the anal canal.

Coccygectomy is a surgical procedure in which the coccyx or tailbone is removed. It is considered a required treatment for sacrococcygeal teratoma and other germ cell tumors arising from the coccyx. Coccygectomy is the treatment of last resort for coccydynia which has failed to respond to nonsurgical treatment. Non surgical treatments include use of seat cushions, external or internal manipulation and massage of the coccyx and the attached muscles, medications given by local injections under fluoroscopic guidance, and medications by mouth.

Defecography is a type of medical radiological imaging in which the mechanics of a patient's defecation are visualized in real time using a fluoroscope. The anatomy and function of the anorectum and pelvic floor can be dynamically studied at various stages during defecation.

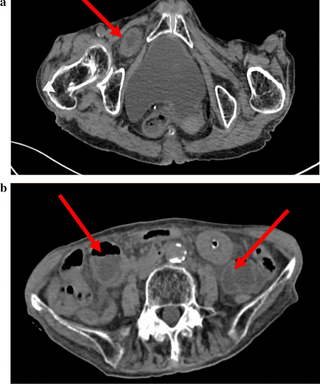

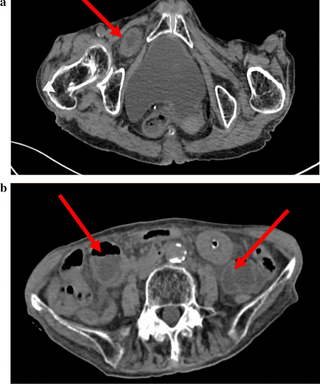

An obturator hernia is a rare type of hernia, encompassing 0.07-1% of all hernias, of the pelvic floor in which pelvic or abdominal contents protrudes through the obturator foramen. The obturator foramen is formed by a branch of the ischial as well as the pubic bone. The canal is typically 2-3 centimeters long and 1 centimeters wide, creating a space for pouches of pre-peritoneal fat.

William Ernest Miles was an English surgeon known for the Miles' operation: an abdomino-perineal excision for rectal cancer.

Acellular dermis is a type of biomaterial derived from processing human or animal tissues to remove cells and retain portions of the extracellular matrix (ECM). These materials are typically cell-free, distinguishing them from classical allografts and xenografts, can be integrated or incorporated into the body, and have been FDA approved for human use for more than 10 years in a wide range of clinical indications.

A perineal tear is a laceration of the skin and other soft tissue structures which, in women, separate the vagina from the anus. Perineal tears mainly occur in women as a result of vaginal childbirth, which strains the perineum. It is the most common form of obstetric injury. Tears vary widely in severity. The majority are superficial and may require no treatment, but severe tears can cause significant bleeding, long-term pain or dysfunction. A perineal tear is distinct from an episiotomy, in which the perineum is intentionally incised to facilitate delivery. Episiotomy, a very rapid birth, or large fetal size can lead to more severe tears which may require surgical intervention.

Obstructed defecation syndrome is a major cause of functional constipation, of which it is considered a subtype. It is characterized by difficult and/or incomplete emptying of the rectum with or without an actual reduction in the number of bowel movements per week. Normal definitions of functional constipation include infrequent bowel movements and hard stools. In contrast, ODS may occur with frequent bowel movements and even with soft stools, and the colonic transit time may be normal, but delayed in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

Descending perineum syndrome refers to a condition where the perineum "balloons" several centimeters below the bony outlet of the pelvis during strain, although this descent may happen without straining. The syndrome was first described in 1966 by Parks et al.

The vaginal support structures are those muscles, bones, ligaments, tendons, membranes and fascia, of the pelvic floor that maintain the position of the vagina within the pelvic cavity and allow the normal functioning of the vagina and other reproductive structures in the female. Defects or injuries to these support structures in the pelvic floor leads to pelvic organ prolapse. Anatomical and congenital variations of vaginal support structures can predispose a woman to further dysfunction and prolapse later in life. The urethra is part of the anterior wall of the vagina and damage to the support structures there can lead to incontinence and urinary retention.