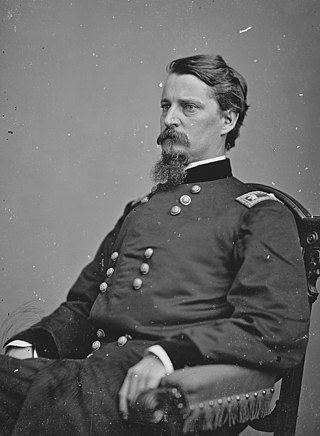

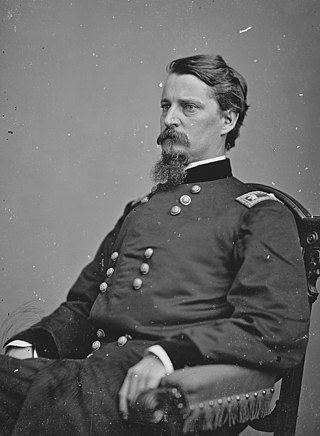

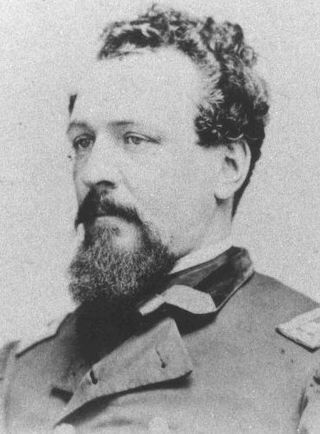

Winfield Scott Hancock was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service in the Mexican–American War and as a Union general in the American Civil War. Known to his Army colleagues as "Hancock the Superb," he was noted in particular for his personal leadership at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. His military service continued after the Civil War, as Hancock participated in the military Reconstruction of the South and the U.S.' western expansion and war with the Native Americans at the Western frontier. This concluded with the Medicine Lodge Treaty. From 1881 to 1885 he was president of the Aztec Club of 1847 for veteran officers of the Mexican-American War.

The 20th Maine Infantry Regiment was a volunteer regiment of the United States Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), most famous for its defense of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, July 1–3, 1863. The 133rd Engineer Battalion of the Maine Army National Guard and the United States Army today carries on the lineage and traditions of the 20th Maine.

John Mansfield was an American lawyer and Republican politician. He was the 15th lieutenant governor of California. During the American Civil War, he was a Union Army officer serving in the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry Regiment in the famous Iron Brigade of the Army of the Potomac. He took command of the regiment during the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg and remained in command until the regiment was disbanded in the fall of 1864. After the war, he received an honorary brevet to brigadier general.

The 69th Pennsylvania Infantry was an infantry regiment in the Union army during the American Civil War.

During the American Civil War, the State of Ohio played a key role in providing troops, military officers, and supplies to the Union army. Due to its central location in the Northern United States and burgeoning population, Ohio was both politically and logistically important to the war effort. Despite the state's boasting a number of very powerful Republican politicians, it was divided politically. Portions of Southern Ohio followed the Peace Democrats and openly opposed President Abraham Lincoln's policies. Ohio played an important part in the Underground Railroad prior to the war, and remained a haven for escaped and runaway slaves during the war years.

During the American Civil War, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania played a critical role in the Union, providing a substantial supply of military personnel, equipment, and leadership to the Federal government. The state raised over 360,000 soldiers for the Federal armies. It served as a significant source of artillery guns, small arms, ammunition, armor for the new revolutionary style of ironclad types of gunboats for the rapidly expanding United States Navy, and food supplies. The Phoenixville Iron Company by itself produced well over 1,000 cannons, and the Frankford Arsenal was a major supply depot.

New York City during the American Civil War (1861–1865) was a bustling American city that provided a major source of troops, supplies, equipment and financing for the Union Army. Powerful New York politicians and newspaper editors helped shape public opinion toward the war effort and the policies of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. The port of New York, a major entry point for immigrants, served as recruiting grounds for the Army. Irish-Americans and German-Americans participated in the war at a high rate.

The 118th Pennsylvania Regiment was a volunteer infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War. They participated in several major conflicts during the war including the Battle of Gettysburg, Siege of Petersburg, and escorted the truce flag of Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Five Forks. The regiment was led by Colonel Charles Prevost until he was seriously injured at the Battle of Shepherdstown in which Lieutenant-Colonel James Gwyn assumed command until the end of the war.

The 74th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was an infantry regiment which served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was one of many all-German regiments in the army, most notably in the XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Its combat record was marred by the perceived poor performance of the entire corps at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, when parts of the corps routed during Confederate attacks.

The York U.S. Army Hospital was one of Pennsylvania's largest military hospitals during the American Civil War. It was established in York, Pennsylvania to treat wounded and sick soldiers of the Union army.

Indiana, a state in the Midwest, played an important role in supporting the Union during the American Civil War. Despite anti-war activity within the state, and southern Indiana's ancestral ties to the South, Indiana was a strong supporter of the Union. Indiana contributed approximately 210,000 Union soldiers, sailors, and marines. Indiana's soldiers served in 308 military engagements during the war; the majority of them in the western theater, between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains. Indiana's war-related deaths reached 25,028. Its state government provided funds to purchase equipment, food, and supplies for troops in the field. Indiana, an agriculturally rich state containing the fifth-highest population in the Union, was critical to the North's success due to its geographical location, large population, and agricultural production. Indiana residents, also known as Hoosiers, supplied the Union with manpower for the war effort, a railroad network and access to the Ohio River and the Great Lakes, and agricultural products such as grain and livestock. The state experienced two minor raids by Confederate forces, and one major raid in 1863, which caused a brief panic in southern portions of the state and its capital city, Indianapolis.

During the American Civil War, Indianapolis, the state capital of Indiana, was a major base of supplies for the Union. Governor Oliver P. Morton, a major supporter of President Abraham Lincoln, quickly made Indianapolis a gathering place to organize and train troops for the Union army. The city became a major railroad hub for troop transport to Confederate lands, and therefore had military importance. Twenty-four military camps were established in the vicinity of Indianapolis. Camp Morton, the initial mustering ground to organize and train the state's Union volunteers in 1861, was designated as a major prisoner-of-war camp for captured Confederate soldiers in 1862. In addition to military camps, a state-owned arsenal was established in the city in 1861, and a federal arsenal in 1862. A Soldiers' Home and a Ladies' Home were established in Indianapolis to house and feed Union soldiers and their families as they passed through the city. Indianapolis residents also supported the Union cause by providing soldiers with food, clothing, equipment, and supplies, despite rising prices and wartime hardships, such as food and clothing shortages. Local doctors aided the sick, some area women provided nursing care, and Indianapolis City Hospital tended to wounded soldiers. Indianapolis sent an estimated 4,000 men into military service; an estimated 700 died during the war. Indianapolis's Crown Hill National Cemetery was established as one of two national military cemeteries established in Indiana in 1866.

The New England state of Connecticut played an important role in the American Civil War, providing arms, equipment, technology, funds, supplies, and soldiers for the Union Army and the Union Navy. Several Connecticut politicians played significant roles in the Federal government and helped shape its policies during the war and the Reconstruction.

The state of New York during the American Civil War was a major influence in national politics, the Union war effort, and the media coverage of the war. New York was the most populous state in the Union during the Civil War, and provided more troops to the U.S. army than any other state, as well as several significant military commanders and leaders. New York sent 400,000 men to the armed forces during the war. 22,000 soldiers died from combat wounds; 30,000 died from disease or accidents; 36 were executed. The state government spent $38 million on the war effort; counties, cities and towns spent another $111 million, especially for recruiting bonuses.

Alexander Henry was an American politician who served three terms as mayor of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from 1858 to 1865. He was elected as a member of the People's Party but served his second and third terms as a member of the Republican Party. He implemented major increases and improvements to the Philadelphia Police Department. During the American Civil War, he was a staunch supporter of the Union but worked to suppress violence against Confederate sympathizers in the city and helped organize civilians to assist in constructing earthworks to defend the city during the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign.

During the American Civil War, the state of Illinois was a major source of troops for the Union Army, and of military supplies, food, and clothing. Situated near major rivers and railroads, Illinois became a major jumping off place early in the war for Ulysses S. Grant's efforts to seize control of the Mississippi and Tennessee rivers. Statewide, public support for the Union was high despite Copperhead sentiment.

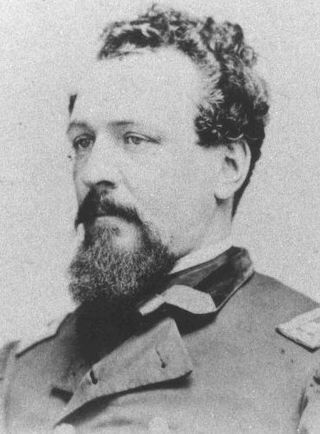

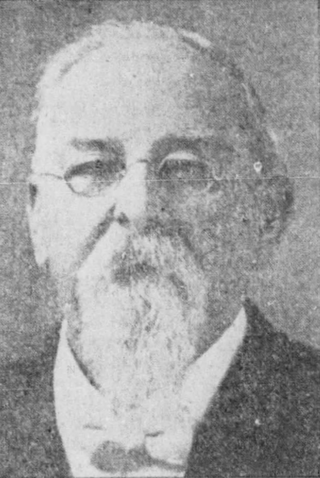

James Gwyn was an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He immigrated at a young age from Ireland in 1846, initially working as a storekeeper in Philadelphia and later as a clerk in New York City. At the onset of the war, in 1861, he enlisted and was commissioned as a captain with the 23rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. He assumed command of the 118th Pennsylvania Regiment in the course of the war. Gwyn led that regiment through many of its 39 recorded battles, including engagements at Seven Pines, Fredericksburg, Shepherdstown, Five Forks, Gettysburg, and Appomattox Court House.

John Mitchell Vanderslice was a United States soldier who fought for the Union Army during the American Civil War as a member of the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry. He received his nation's highest award for valor, the U.S. Medal of Honor, for being the first man to reach the rifle pits of the Confederate States Army during a charge made by his regiment on CSA fortifications in the Battle of Hatcher's Run, Virginia on February 6, 1865.

Henry Conner was an American hotelier, restaurateur, and politician. He was a member of the Wisconsin State Senate, representing Vernon and La Crosse counties during the 1891 and 1893 sessions. Earlier, he served as a Union Army officer during the American Civil War, and lost his right leg due to wounds. His last name was sometimes spelled Connor.

The 47th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, officially the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and sometimes referred to simply as the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War and the early months of the Reconstruction era. It was formed by adults and teenagers from small towns and larger metropolitan areas in the central, northeastern, and southeastern regions of Pennsylvania.