Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of the last great representatives of Romanticism in Russian classical music. Early influences of Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and other Russian composers gave way to a thoroughly personal idiom notable for its song-like melodicism, expressiveness, dense contrapuntal textures, and rich orchestral colours. The piano is featured prominently in Rachmaninoff's compositional output and he used his skills as a performer to fully explore the expressive and technical possibilities of the instrument.

The Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43, is a concertante work written by Sergei Rachmaninoff for piano and orchestra, closely resembling a piano concerto, all in a single movement. Rachmaninoff wrote the work at his summer home, the Villa Senar in Switzerland, according to the score, from 3 July to 18 August 1934. Rachmaninoff himself, a noted performer of his own works, played the piano part at the piece's premiere on 7 November 1934, at the Lyric Opera House in Baltimore, Maryland, with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski.

Sergei Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30, was composed in the summer of 1909. The piece was premiered on November 28 of that year in New York City with the composer as soloist, accompanied by the New York Symphony Society under Walter Damrosch. The work has the reputation of being one of the most technically challenging piano concertos in the standard classical piano repertoire.

Sergei Rachmaninoff's Trio élégiaque No. 2 in D minor, Op. 9 is a piano trio which he began composing on 25 October 1893 and completed on 15 December that year. It was written in memory of Tchaikovsky and was inscribed with the dedication "In Memory of a Great Artist". It was first performed in Moscow on 31 January 1894 by Rachmaninoff himself, the violinist Julius Conus, and the cellist Anatoli Brandukov.

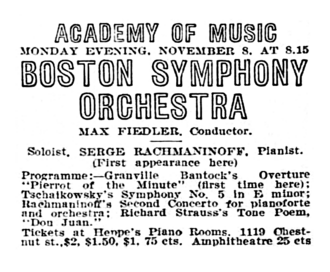

The Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27, is a four-movement composition for orchestra written from October 1906 to April 1907 by the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. The premiere was performed at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg on 26 January 1908, with the composer conducting. Its duration is approximately 60 minutes when performed uncut; cut performances can be as short as 35 minutes. The score is dedicated to Sergei Taneyev, a Russian composer, teacher, theorist, author, and pupil of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The piece remains one of the composer's most popular and best known compositions.

The Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 13, is a four-movement composition for orchestra written from January to October 1895 by the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. He composed it at his Ivanovka estate near Tambov, Russia. Despite its poor initial reception, the symphony is now seen as a dynamic representation of the Russian symphonic tradition, with British composer Robert Simpson calling it "a powerful work in its own right, stemming from Borodin and Tchaikovsky, but convinced, individual, finely constructed, and achieving a genuinely tragic and heroic expression that stands far above the pathos of his later music."

Piano Concerto No. 4 in G minor, Op. 40, is a major work by Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, completed in 1926. The work exists in three versions. Following its unsuccessful premiere, the composer made cuts and other amendments before publishing it in 1928. With continued lack of success, he withdrew the work, eventually revising and republishing it in 1941. The original manuscript version was released in 2000 by the Rachmaninoff Estate to be published and recorded. The work is dedicated to Nikolai Medtner, who in turn dedicated his Second Piano Concerto to Rachmaninoff the following year.

Sergei Rachmaninoff composed his Piano Concerto No. 1 in F♯ minor, Op. 1, in 1891, at age 17-18. He dedicated the work to Alexander Siloti. He revised the work thoroughly in 1917.

Suite No. 1 in G minor, Op. 5, is a suite for two pianos written by Sergei Rachmaninoff. The suite was a musical depiction of four poems written in the summer of 1893 at the Lysikof estate in Lebeden, Kharkov. The premiere took place in Moscow, on November 30, 1893, played by Rachmaninoff himself alongside Pavel Pabst. The work was dedicated to Tchaikovsky, who intended to attend the work's premiere, but died five weeks prior. Its four movements alongside their respective poems are as follows:

Suite No. 2, Op. 17, is a composition for two pianos by Sergei Rachmaninoff, written in Italy in the first months of 1901. Alongside his Second Piano Concerto, Op. 18, it confirmed a return of creativity for the composer after four unproductive years caused by the negative critical reception of his First Symphony, Op. 13. The Suite was first performed on November 24 that year by the composer and his cousin Alexander Siloti.

The Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 44, is a three-movement composition for orchestra written from 1935 to 1936 by the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. The Third Symphony is considered a transitional work in Rachmaninoff's output. In melodic outline and rhythm it is his most expressively Russian symphony, particularly in the dance rhythms of the finale. What was groundbreaking in this symphony was its greater economy of utterance compared to its two predecessors. This sparer style, first apparent in the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, enhances the emotional power of the work.

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45, is an orchestral suite in three movements completed in October 1940 by Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. It is his final major composition, and his only piece written in its entirety while living in the United States.

Isle of the Dead, Op. 29, is a symphonic poem composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff, written in the key of A minor. The piece was inspired by a black and white reproduction of Arnold Böcklin's painting Isle of the Dead, which he saw in Paris in 1907. He composed the work from January to March of 1909, and later made numerous revisions to the piece, which included significant cuts.

The Bells, Op. 35, is a choral symphony by Sergei Rachmaninoff, written in 1913 and premiered in St Petersburg on 30 November that year under the composer's baton. The words are from the poem The Bells by Edgar Allan Poe, very freely translated into Russian by the symbolist poet Konstantin Balmont. The traditional Gregorian melody Dies Irae is used frequently throughout the work. It was one of Rachmaninoff's two favorite compositions, along with his All-Night Vigil, and is considered by some to be his secular choral masterpiece. Rachmaninoff called the work both a choral symphony and (unofficially) his Third Symphony shortly after writing it; however, he would later write a purely instrumental Third Symphony at his new villa in Switzerland. Rachmaninoff dedicated The Bells to Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. The US Premiere of the work was given by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra and Chorus on 6 February 1920 and the UK Premiere by Sir Henry Wood and the Liverpool Philharmonic and Chorus on 15 March 1921.

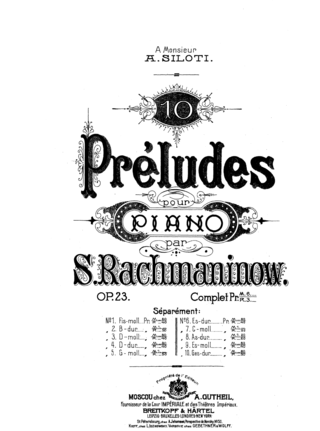

Ten Preludes, Op. 23, is a set of ten preludes for solo piano, composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1901 and 1903. This set includes the famous Prelude in G minor.

Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28, is a piano sonata by Sergei Rachmaninoff, completed in 1908. It is the first of three "Dresden pieces", along with the Symphony No. 2 and part of an opera, which were composed in the quiet city of Dresden, Germany. It was originally inspired by Goethe's tragic play Faust; although Rachmaninoff abandoned the idea soon after beginning composition, traces of this influence can still be found. After numerous revisions and substantial cuts made at the advice of his colleagues, he completed it on April 11, 1908. Konstantin Igumnov gave the premiere in Moscow on October 17, 1908. It received a lukewarm response there, and remains one of the least performed of Rachmaninoff's works.

Caprice bohémien, Op. 12, also known as the "Capriccio on Gypsy Themes", is a symphonic poem for orchestra composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff from 1892 to 1894.

Russian Rhapsody is a piece for two pianos in E minor composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1891, when he was 18 years old. It is more accurately described as a set of variations on a theme, rather than a true rhapsody. It was premièred on October 29, 1891, and its performance lasts approximately nine minutes.

The Études-Tableaux, Op. 33, is the first of two sets of piano études composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff. They were intended to be "picture pieces", essentially "musical evocations of external visual stimuli". But Rachmaninoff did not disclose what inspired each one, stating: "I do not believe in the artist that discloses too much of his images. Let [the listener] paint for themselves what it most suggests." However, he willingly shared sources for a few of these études with the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi when Respighi orchestrated them in 1930.