Armadillos are New World placental mammals in the order Cingulata. They form part of the superorder Xenarthra, along with the anteaters and sloths. 21 extant species of armadillo have been described, some of which are distinguished by the number of bands on their armor. All species are native to the Americas, where they inhabit a variety of different environments.

Xenarthra is a major clade of placental mammals native to the Americas. There are 31 living species: the anteaters, tree sloths, and armadillos. Extinct xenarthrans include the glyptodonts, pampatheres and ground sloths. Xenarthrans originated in South America during the late Paleocene about 60 million years ago. They evolved and diversified extensively in South America during the continent's long period of isolation in the early to mid Cenozoic Era. They spread to the Antilles by the early Miocene and, starting about 3 million years ago, spread to Central and North America as part of the Great American Interchange. Nearly all of the formerly abundant megafaunal xenarthrans became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene.

The pink fairy armadillo is the smallest species of armadillo, first described by Richard Harlan in 1825. This solitary, desert-adapted animal is endemic to central Argentina and can be found inhabiting sandy plains, dunes, and scrubby grasslands.

The giant armadillo, colloquially tatu-canastra, tatou, ocarro or tatú carreta, is the largest living species of armadillo. It lives in South America, ranging throughout as far south as northern Argentina. This species is considered vulnerable to extinction.

Cingulata, part of the superorder Xenarthra, is an order of armored New World placental mammals. Dasypodids and chlamyphorids, the armadillos, are the only surviving families in the order. Two groups of cingulates much larger than extant armadillos existed until recently: pampatheriids, which reached weights of up to 200 kg (440 lb) and chlamyphorid glyptodonts, which attained masses of 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) or more.

The six-banded armadillo, also known as the yellow armadillo, is an armadillo found in South America. The sole extant member of its genus, it was first described by Swedish zoologist Carl Linnaeus in 1758. The six-banded armadillo is typically between 40 and 50 centimeters in head-and-body length, and weighs 3.2 to 6.5 kilograms. The carapace is pale yellow to reddish brown, marked by scales of equal length, and scantily covered by buff to white bristle-like hairs. The forefeet have five distinct toes, each with moderately developed claws.

The southern long-nosed armadillo is a species of armadillo native to South America.

The Chacoan naked-tailed armadillo is a species of South American armadillo.

The bighairy armadillo is one of the largest and most numerous armadillos in South America. It lives from sea level to altitudes of up to 1,300 meters across the southern portion of South America, and can be found in grasslands, forests, and savannahs, and has even started claiming agricultural areas as its home. It is an accomplished digger and spends most of its time below ground. It makes both temporary and long-term burrows, depending on its food source. In Spanish it is colloquially known as "peludo".

Yepes's mulita or the Yungas lesser long-nosed armadillo is a species of armadillo in the family Dasypodidae. It is endemic to Argentina and Bolivia. Its natural habitat is subtropical dry forests. The species was renamed D. yepesi because the type of D. mazzai was suspected to correspond of other species of Dasypus, which it was later proved wrong, becoming D. yepesi a synonym of D. mazzai.

Pampatheriidae is an extinct family of large cingulates related to armadillos. They first appeared in South America during the mid-Miocene, and Holmesina and Pampatherium spread to North America during the Pleistocene after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama as part of the Great American Interchange. They became extinct as part of the end-Pleistocene extinctions, about 12,000 years ago.

Euphractinae is an armadillo subfamily in the family Chlamyphoridae.

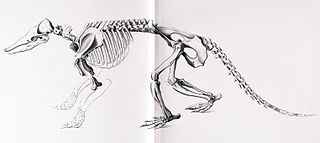

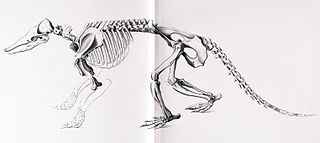

Stegotherium is an extinct genus of long-nosed armadillo, belonging to the Dasypodidae family alongside the nine-banded armadillo. It is currently the only genus recognized as a member of the tribe Stegotheriini. It lived during the Early Miocene of Patagonia and was found in Colhuehuapian rocks from the Sarmiento Formation, Santacrucian rocks from the Santa Cruz Formation, and potentially also in Colloncuran rocks from the Middle Miocene Collón Curá Formation. Its strange, almost toothless and elongated skull indicates a specialization for myrmecophagy, the eating of ants, unique among the order Cingulata, which includes pampatheres, glyptodonts and all the extant species of armadillos.

Chlamyphoridae is a family of cingulate mammals. While glyptodonts have traditionally been considered stem-group cingulates outside the group that contains modern armadillos, there had been speculation that the extant family Dasypodidae could be paraphyletic based on morphological evidence. In 2016, an analysis of Doedicurus mtDNA found it was, in fact, nested within the modern armadillos as the sister group of a clade consisting of Chlamyphorinae and Tolypeutinae. For this reason, all extant armadillos but Dasypus were relocated to a new family.

Utaetus is an extinct genus of mammal in the order Cingulata, related to the modern armadillos. The genus contains two species, Utaetus buccatus and U. magnum. It lived in the Late Paleocene to Late Eocene and its fossil remains were found in Argentina and Brazil in South America.

Epipeltephilus is an extinct genus of armadillo, belonging to the family Peltephilidae, the "horned armadillos", whose most famous relative was Peltephilus. Epipeltephilus is the last known member of its family, becoming extinct during the Chasicoan period. It was found in the Rio Mayo Formation and the Arroyo Chasicó Formation of Argentina, and in northern Chile.

Prozaedyus is an extinct genus of chlamyphorid armadillo that lived during the Middle Oligocene and Middle Miocene in what is now South America.

Dasypus neogaeus is an extinct species of armadillo, belonging to the genus Dasypus, alongside the modern nine-banded armadillo. The only known fossil is a single osteoderm, though it has been lost, that was found in the Late Miocene strata of Argentina.

Peltephilidae is a family of South American cingulates (armadillos) that lived for over 40 million years, but peaked in diversity towards the end of the Oligocene and beginning of the Miocene in what is now Argentina. They were exclusive to South America due to its geographic isolation at the time, one of many of the continent's strange endemic families. Peltephilids are one of the earliest known cingulates, diverging from the rest of Cingulata in the Early Eocene.