Americium is a synthetic radioactive chemical element with the symbol Am and atomic number 95. It is a transuranic member of the actinide series, in the periodic table located under the lanthanide element europium, and thus by analogy was named after the Americas.

The actinide or actinoid series encompasses the 15 metallic chemical elements with atomic numbers from 89 to 103, actinium through lawrencium. The actinide series derives its name from the first element in the series, actinium. The informal chemical symbol An is used in general discussions of actinide chemistry to refer to any actinide.

Berkelium is a transuranic radioactive chemical element with the symbol Bk and atomic number 97. It is a member of the actinide and transuranium element series. It is named after the city of Berkeley, California, the location of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory where it was discovered in December 1949. Berkelium was the fifth transuranium element discovered after neptunium, plutonium, curium and americium.

Curium is a transuranic, radioactive chemical element with the symbol Cm and atomic number 96. This actinide element was named after eminent scientists Marie and Pierre Curie, both known for their research on radioactivity. Curium was first intentionally made by the team of Glenn T. Seaborg, Ralph A. James, and Albert Ghiorso in 1944, using the cyclotron at Berkeley. They bombarded the newly discovered element plutonium with alpha particles. This was then sent to the Metallurgical Laboratory at University of Chicago where a tiny sample of curium was eventually separated and identified. The discovery was kept secret until after the end of World War II. The news was released to the public in November 1947. Most curium is produced by bombarding uranium or plutonium with neutrons in nuclear reactors – one tonne of spent nuclear fuel contains ~20 grams of curium.

Neptunium is a chemical element with the symbol Np and atomic number 93. A radioactive actinide metal, neptunium is the first transuranic element. Its position in the periodic table just after uranium, named after the planet Uranus, led to it being named after Neptune, the next planet beyond Uranus. A neptunium atom has 93 protons and 93 electrons, of which seven are valence electrons. Neptunium metal is silvery and tarnishes when exposed to air. The element occurs in three allotropic forms and it normally exhibits five oxidation states, ranging from +3 to +7. It is radioactive, poisonous, pyrophoric, and capable of accumulating in bones, which makes the handling of neptunium dangerous.

Redox is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a decrease in the oxidation state.

In chemistry, a reducing agent is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an electron recipient. Examples of substances that are commonly reducing agents include the Earth metals, formic acid, oxalic acid, and sulfite compounds.

A substance is pyrophoric if it ignites spontaneously in air at or below 54 °C (129 °F) or within 5 minutes after coming into contact with air. Examples are organolithium compounds and triethylborane. Pyrophoric materials are often water-reactive as well and will ignite when they contact water or humid air. They can be handled safely in atmospheres of argon or nitrogen. Class D fire extinguishers are designated for use in fires involving pyrophoric materials. A related concept is hypergolicity, in which two compounds spontaneously ignite when mixed.

Silane is an inorganic compound with chemical formula, SiH4. It is a colourless, pyrophoric, toxic gas with a sharp, repulsive smell, somewhat similar to that of acetic acid. Silane is of practical interest as a precursor to elemental silicon. Silane with alkyl groups are effective water repellents for mineral surfaces such as concrete and masonry. Silanes with both organic and inorganic attachments are used as coupling agents.

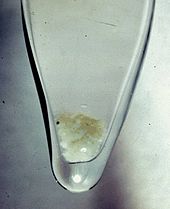

Curium(III) oxide is a compound composed of curium and oxygen with the chemical formula Cm2O3. It is a crystalline solid with a unit cell that contains two curium atoms and three oxygen atoms. The simplest synthesis equation involves the reaction of curium(III) metal with O2−: 2 Cm3+ + 3 O2− ---> Cm2O3. Curium trioxide can exist as five polymorphic forms. Two of the forms exist at extremely high temperatures, making it difficult for experimental studies to be done on the formation of their structures. The three other possible forms which curium sesquioxide can take are the body-centered cubic form, the monoclinic form, and the hexagonal form. Curium(III) oxide is either white or light tan in color and, while insoluble in water, is soluble in inorganic and mineral acids. Its synthesis was first recognized in 1955.

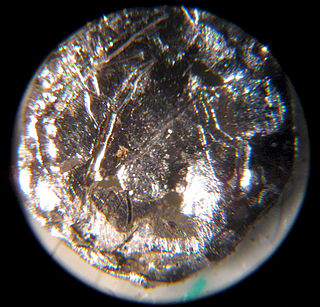

Plutonium hydride is a non-stoichiometric chemical compound with the formula PuH2+x. It is one of two characterised hydrides of plutonium, the other is PuH3. PuH2 is non-stoichiometric with a composition range of PuH2 – PuH2.7. Additionally metastable stoichiometries with an excess of hydrogen (PuH2.7 – PuH3) can be formed. PuH2 has a cubic structure. It is readily formed from the elements at 1 atmosphere at 100–200 °C: When the stoichiometry is close to PuH2 it has a silver appearance, but gets blacker as the hydrogen content increases, additionally the color change is associated with a reduction in conductivity.

Uranium compounds are compounds formed by the element uranium (U). Although uranium is a radioactive actinide, its compounds are well studied due to its long half-life and its applications. It usually forms in the +4 and +6 oxidation states, although it can also form in other oxidation states.

Organoactinide chemistry is the science exploring the properties, structure and reactivity of organoactinide compounds, which are organometallic compounds containing a carbon to actinide chemical bond.

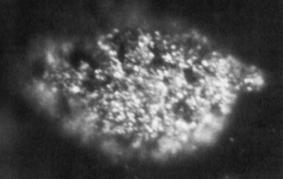

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four oxidation states. It reacts with carbon, halogens, nitrogen, silicon, and hydrogen. When exposed to moist air, it forms oxides and hydrides that can expand the sample up to 70% in volume, which in turn flake off as a powder that is pyrophoric. It is radioactive and can accumulate in bones, which makes the handling of plutonium dangerous.

The oxidation state of oxygen is −2 in almost all known compounds of oxygen. The oxidation state −1 is found in a few compounds such as peroxides. Compounds containing oxygen in other oxidation states are very uncommon: −1⁄2 (superoxides), −1⁄3 (ozonides), 0, +1⁄2 (dioxygenyl), +1, and +2.

Uranium hydride, also called uranium trihydride (UH3), is an inorganic compound and a hydride of uranium.

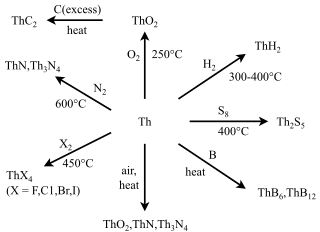

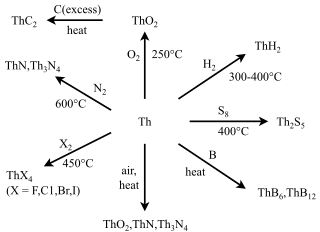

Many compounds of thorium are known: this is because thorium and uranium are the most stable and accessible actinides and are the only actinides that can be studied safely and legally in bulk in a normal laboratory. As such, they have the best-known chemistry of the actinides, along with that of plutonium, as the self-heating and radiation from them is not enough to cause radiolysis of chemical bonds as it is for the other actinides. While the later actinides from americium onwards are predominantly trivalent and behave more similarly to the corresponding lanthanides, as one would expect from periodic trends, the early actinides up to plutonium have relativistically destabilised and hence delocalised 5f and 6d electrons that participate in chemistry in a similar way to the early transition metals of group 3 through 8: thus, all their valence electrons can participate in chemical reactions, although this is not common for neptunium and plutonium.

Curium compounds are compounds containing the element curium (Cm). Curium usually forms compounds in the +3 oxidation state, although compounds with curium in the +4, +5 and +6 oxidation states are also known.

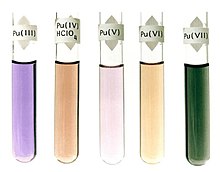

Neptunium compounds are compounds containg the element neptunium (Np). Neptunium has five ionic oxidation states ranging from +3 to +7 when forming chemical compounds, which can be simultaneously observed in solutions. It is the heaviest actinide that can lose all its valence electrons in a stable compound. The most stable state in solution is +5, but the valence +4 is preferred in solid neptunium compounds. Neptunium metal is very reactive. Ions of neptunium are prone to hydrolysis and formation of coordination compounds.

Americium compounds are compounds containing the element americium (Am). These compounds can form in the +2, +3 and +4, although the +3 oxidation state is the most common. The +5, +6 and +7 oxidation states have also been reported.