Americium is a synthetic chemical element; it has symbol Am and atomic number 95. It is radioactive and a transuranic member of the actinide series in the periodic table, located under the lanthanide element europium and was thus named after the Americas by analogy.

The actinide or actinoid series encompasses at least the 14 metallic chemical elements in the 5f series, with atomic numbers from 89 to 102, actinium through nobelium. The actinide series derives its name from the first element in the series, actinium. The informal chemical symbol An is used in general discussions of actinide chemistry to refer to any actinide.

Curium is a synthetic chemical element; it has symbol Cm and atomic number 96. This transuranic actinide element was named after eminent scientists Marie and Pierre Curie, both known for their research on radioactivity. Curium was first intentionally made by the team of Glenn T. Seaborg, Ralph A. James, and Albert Ghiorso in 1944, using the cyclotron at Berkeley. They bombarded the newly discovered element plutonium with alpha particles. This was then sent to the Metallurgical Laboratory at University of Chicago where a tiny sample of curium was eventually separated and identified. The discovery was kept secret until after the end of World War II. The news was released to the public in November 1947. Most curium is produced by bombarding uranium or plutonium with neutrons in nuclear reactors – one tonne of spent nuclear fuel contains ~20 grams of curium.

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of these reactions. The specific nuclear reaction may be the fission of heavy isotopes. A nuclear chain reaction releases several million times more energy per reaction than any chemical reaction.

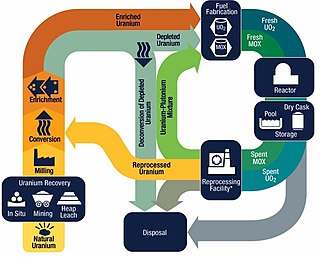

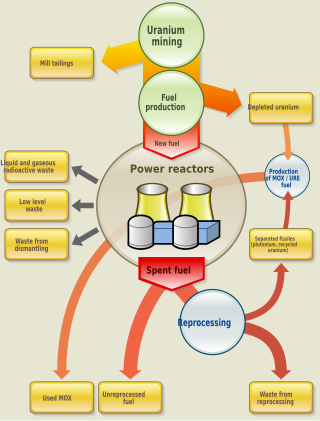

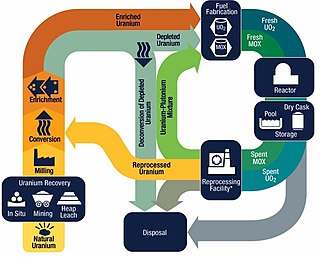

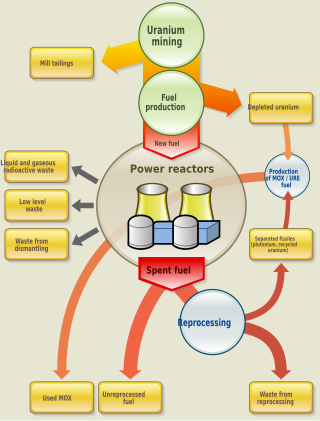

The nuclear fuel cycle, also called nuclear fuel chain, is the progression of nuclear fuel through a series of differing stages. It consists of steps in the front end, which are the preparation of the fuel, steps in the service period in which the fuel is used during reactor operation, and steps in the back end, which are necessary to safely manage, contain, and either reprocess or dispose of spent nuclear fuel. If spent fuel is not reprocessed, the fuel cycle is referred to as an open fuel cycle ; if the spent fuel is reprocessed, it is referred to as a closed fuel cycle.

Nuclear reprocessing is the chemical separation of fission products and actinides from spent nuclear fuel. Originally, reprocessing was used solely to extract plutonium for producing nuclear weapons. With commercialization of nuclear power, the reprocessed plutonium was recycled back into MOX nuclear fuel for thermal reactors. The reprocessed uranium, also known as the spent fuel material, can in principle also be re-used as fuel, but that is only economical when uranium supply is low and prices are high. Nuclear reprocessing may extend beyond fuel and include the reprocessing of other nuclear reactor material, such as Zircaloy cladding.

Mixed oxide fuel, commonly referred to as MOX fuel, is nuclear fuel that contains more than one oxide of fissile material, usually consisting of plutonium blended with natural uranium, reprocessed uranium, or depleted uranium. MOX fuel is an alternative to the low-enriched uranium fuel used in the light-water reactors that predominate nuclear power generation.

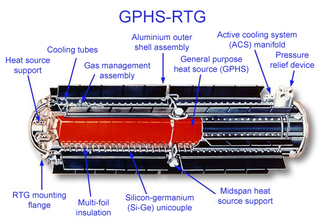

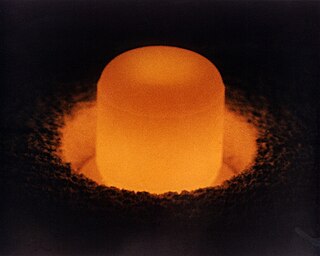

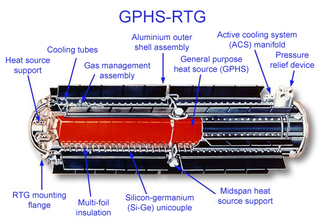

A radioisotope thermoelectric generator, sometimes referred to as a radioisotope power system (RPS), is a type of nuclear battery that uses an array of thermocouples to convert the heat released by the decay of a suitable radioactive material into electricity by the Seebeck effect. This type of generator has no moving parts and is ideal for deployment in remote and harsh environments for extended periods with no risk of parts wearing out or malfunctioning.

A fast-neutron reactor (FNR) or fast-spectrum reactor or simply a fast reactor is a category of nuclear reactor in which the fission chain reaction is sustained by fast neutrons, as opposed to slow thermal neutrons used in thermal-neutron reactors. Such a fast reactor needs no neutron moderator, but requires fuel that is relatively rich in fissile material when compared to that required for a thermal-neutron reactor. Around 20 land based fast reactors have been built, accumulating over 400 reactor years of operation globally. The largest of this was the Superphénix Sodium cooled fast reactor in France that was designed to deliver 1,242 MWe. Fast reactors have been intensely studied since the 1950s, as they provide certain advantages over the existing fleet of water cooled and water moderated reactors. These are:

Nuclear fuel is material used in nuclear power stations to produce heat to power turbines. Heat is created when nuclear fuel undergoes nuclear fission.

Plutonium-239 is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three main isotopes demonstrated usable as fuel in thermal spectrum nuclear reactors, along with uranium-235 and uranium-233. Plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,110 years.

Uranium dioxide or uranium(IV) oxide , also known as urania or uranous oxide, is an oxide of uranium, and is a black, radioactive, crystalline powder that naturally occurs in the mineral uraninite. It is used in nuclear fuel rods in nuclear reactors. A mixture of uranium and plutonium dioxides is used as MOX fuel. Prior to 1960, it was used as yellow and black color in ceramic glazes and glass.

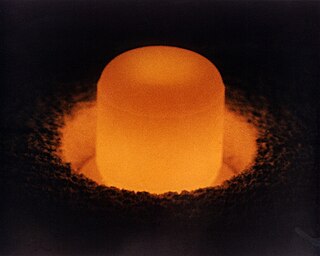

Plutonium-238 is a radioactive isotope of plutonium that has a half-life of 87.7 years.

Spent nuclear fuel, occasionally called used nuclear fuel, is nuclear fuel that has been irradiated in a nuclear reactor. It is no longer useful in sustaining a nuclear reaction in an ordinary thermal reactor and, depending on its point along the nuclear fuel cycle, it will have different isotopic constituents than when it started.

The Systems Nuclear Auxiliary POWER (SNAP) program was a program of experimental radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) and space nuclear reactors flown during the 1960s by NASA.

Since the mid-20th century, plutonium in the environment has been primarily produced by human activity. The first plants to produce plutonium for use in cold war atomic bombs were at the Hanford nuclear site, in Washington, and Mayak nuclear plant, in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia. Over a period of four decades, "both released more than 200 million curies of radioactive isotopes into the surrounding environment – twice the amount expelled in the Chernobyl disaster in each instance".

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four oxidation states. It reacts with carbon, halogens, nitrogen, silicon, and hydrogen. When exposed to moist air, it forms oxides and hydrides that can expand the sample up to 70% in volume, which in turn flake off as a powder that is pyrophoric. It is radioactive and can accumulate in bones, which makes the handling of plutonium dangerous.

Neptunium(IV) oxide, or neptunium dioxide, is a radioactive, olive green cubic crystalline solid with the formula NpO2. It emits both α- and γ-particles.

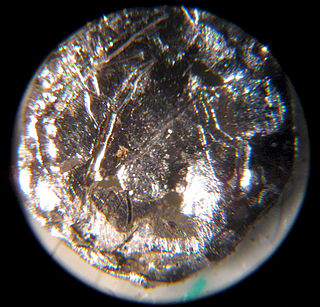

Corium, also called fuel-containing material (FCM) or lava-like fuel-containing material (LFCM), is a material that is created in a nuclear reactor core during a nuclear meltdown accident. Resembling lava in consistency, it consists of a mixture of nuclear fuel, fission products, control rods, structural materials from the affected parts of the reactor, products of their chemical reaction with air, water, steam, and in the event that the reactor vessel is breached, molten concrete from the floor of the reactor room.

Nuclear transmutation is the conversion of one chemical element or an isotope into another chemical element. Nuclear transmutation occurs in any process where the number of protons or neutrons in the nucleus of an atom is changed.