Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the 2002 Rome Declaration of Statute of the International Criminal Court. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, such as schools and hospitals by people of different races. Specifically, it may be applied to activities such as eating in restaurants, drinking from water fountains, using public toilets, attending schools, going to films, riding buses, renting or purchasing homes or renting hotel rooms. In addition, segregation often allows close contact between members of different racial or ethnic groups in hierarchical situations, such as allowing a person of one race to work as a servant for a member of another race.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that came to be known as "separate but equal". Notably the court ruled the existence of laws based upon race was not inherently racial discrimination. The decision legitimized the many state laws re-establishing racial segregation that had been passed in the American South after the end of the Reconstruction era (1865–1877).

Miscegenation is sexual relations or marriage between people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms miscere and genus ("race"). The word first appeared in Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro, a hoax anti-abolitionist pamphlet David Goodman Croly and others published anonymously in advance of the 1864 U.S. presidential election. The term came to be associated with laws that banned interracial marriage and sex, which were known as anti-miscegenation laws.

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protection" under the law to all people. Under the doctrine, as long as the facilities provided to each "race" were equal, state and local governments could require that services, facilities, public accommodations, housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation be segregated by "race", which was already the case throughout the states of the former Confederacy. The phrase was derived from a Louisiana law of 1890, although the law actually used the phrase "equal but separate".

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The case involved Mildred Loving, a woman of color, and her white husband Richard Loving, who in 1958 were sentenced to a year in prison for marrying each other. Their marriage violated Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which criminalized marriage between people classified as "white" and people classified as "colored". The Lovings appealed their conviction to the Supreme Court of Virginia, which upheld it. They then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear their case.

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian." The act, an outgrowth of eugenist and scientific racist propaganda, was pushed by Walter Plecker, a white supremacist and eugenist who held the post of registrar of Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics.

In societies that regard some races or ethnic groups of people as dominant or superior and others as subordinate or inferior, hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union to the subordinate group. The opposite practice is hyperdescent, in which children are assigned to the race that is considered dominant or superior.

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a cohabitation law of Florida, part of the state's anti-miscegenation laws, was unconstitutional. The law prohibited habitual cohabitation by two unmarried people of opposite sex, if one was black and the other was white. The decision overturned Pace v. Alabama (1883), which had declared such statutes constitutional. It did not overturn the related Florida statute that prohibited interracial marriage between whites and blacks. Such laws were declared unconstitutional in 1967 in Loving v. Virginia.

Perez v. Sharp, also known as Perez v. Lippold or Perez v. Moroney, is a 1948 case decided by the Supreme Court of California in which the court held by a 4–3 majority that the state's ban on interracial marriage violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Racial segregation in the United States is the systematic separation of facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation on racial grounds. The term is mainly used in reference to the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites, but it is also used in reference to the separation of other ethnic minorities from majority and mainstream communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage, and the separation of roles within an institution. Notably, in the United States Armed Forces up until 1948, black units were typically separated from white units but were still led by white officers.

Legislation seeking to direct relations between racial or ethnic groups in the United States has had several historical phases, developing from the European colonization of the Americas, the triangular slave trade, and the American Indian Wars. The 1776 Declaration of Independence included the statement that "all men are created equal," which has ultimately inspired actions and legislation against slavery and racial discrimination. Such actions have led to passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 (1883), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama's anti-miscegenation statute was constitutional. This ruling was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1964 in McLaughlin v. Florida and in 1967 in Loving v. Virginia. Pace v. Alabama is one of the oldest court cases in America pertaining to interracial sex.

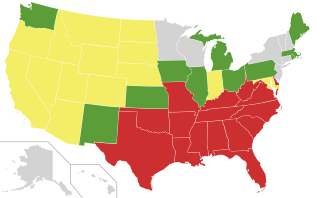

Interracial marriage has been legal throughout the United States since at least the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court decision Loving v. Virginia (1967) that held that anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional via the 14th Amendment adopted in 1868. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in the court opinion that "the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the State." Since Loving, several states repealed their defunct bans, the last of which was Alabama in a 2000 referendum. Interracial marriages have been formally protected by federal statute through the Respect for Marriage Act since 2022.

Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80; 87 S.E.2d 749 (1955), is a case regarding interracial marriage. The case was decided by the Supreme Court of Virginia on June 13, 1955. The Court held the marriage between the appellant and the appellee to be void under the Code of Virginia (1950).

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different races.

In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws were passed by most states to prohibit interracial marriage, and in some cases also prohibit interracial sexual relations. Some such laws predate the establishment of the United States, some dating to the later 17th or early 18th century, a century or more after the complete racialization of slavery. Nine states never enacted such laws; 25 states had repealed their laws by 1967, when the United States Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that such laws were unconstitutional in the remaining 16 states. The term miscegenation was first used in 1863, during the American Civil War, by journalists to discredit the abolitionist movement by stirring up debate over the prospect of interracial marriage after the abolition of slavery.

John H. Van Evrie (1814–1896) was a Canadian-born American physician and defender of slavery best known as the editor of the Weekly Day Book and the author of several books on race and slavery which reproduced the ideas of scientific racism for a popular audience. He was also the proprietor of the publishing company Van Evrie, Horton & Company. Van Evrie was described by the historian George M. Fredrickson as "perhaps the first professional racist in American history." His thought, which lacked significant scientific evidence even for the time, emphasized the inferiority of black people to white people, defended slavery as practiced in the United States and attacked abolitionism, while opposing class distinctions among white people and the oppression of the white working class. He repeatedly put "slave" and "slavery" in quotation marks, because he did not think these were the right words for enslaved Blacks.

Ophelia (Catata) Paquet was a Tillamook Indian woman involved in a famous Oregon miscegenation court case in year 1919. The case's issue was whether Ophelia Paquet could inherit her deceased Caucasian husband's estate in the U.S. state of Oregon. Her case exemplifies the role that marriage has in the transmission of property and how race can affect gender complications.

The Kalergi Plan, sometimes called the Coudenhove-Kalergi Conspiracy, is a far-right, antisemitic, white genocide conspiracy theory. The theory claims that Austrian-Japanese politician Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi concocted a plot to mix white Europeans with other races via immigration. The conspiracy theory is most often associated with European groups and parties, but it has also spread to North American politics.