Moon Edwin Landrieu was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 56th mayor of New Orleans from 1970 to 1978. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented New Orleans' Twelfth Ward in the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1960 to 1966, served on the New Orleans City Council as a member at-large from 1966 to 1970, and was the United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under U.S. president Jimmy Carter from 1979 to 1981.

Mary Loretta Landrieu is an American entrepreneur and politician who served as a United States senator from Louisiana from 1997 to 2015. A member of the Democratic Party, Landrieu served as the Louisiana State Treasurer from 1988 to 1996, and in the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1980 to 1988.

Monument Avenue is a tree-lined grassy mall dividing the eastbound and westbound traffic in Richmond, Virginia, originally named for its emblematic complex of structures honoring those who fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Between 1900 and 1925, Monument Avenue greatly expanded with architecturally significant houses, churches, and apartment buildings. Four of the bronze statues representing J. E. B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis and Matthew Fontaine Maury were removed from their memorial pedestals amidst civil unrest in July 2020. The Robert E. Lee monument was handled differently as it was owned by the Commonwealth, in contrast with the other monuments which were owned by the city. Dedicated in 1890, it was removed on September 8, 2021. All these monuments, including their pedestals, have now been removed completely from the Avenue. The last remaining statue on Monument Avenue is the Arthur Ashe Monument, memorializing the African-American tennis champion, dedicated in 1996.

Mitchell Joseph Landrieu is an American lawyer and politician who served as Mayor of New Orleans from 2010 to 2018. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana from 2004 to 2010.

The Confederate War Memorial was a 65 foot (20 m)-high monument that pays tribute to soldiers and sailors from Texas who served with the Confederate States of America (CSA) during the American Civil War. The monument was dedicated in 1897, following the laying of its cornerstone the previous year. Originally located in Sullivan Park near downtown Dallas, Texas, United States, the monument was relocated in 1961 to the nearby Pioneer Park Cemetery in the Convention Center District, next to the Dallas Convention Center and Pioneer Plaza.

The Statue of Lenin is a 16 ft (5 m) bronze statue of Russian communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle, Washington, United States. It was created by Bulgarian-born Slovak sculptor Emil Venkov and initially put on display in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in 1988, the year before the Velvet Revolution. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a wave of de-Leninization brought about the fall of many monuments in the former Soviet sphere. In 1993, the statue was bought by an American who had found it lying in a scrapyard. He brought it home with him to Washington State but died before he could carry out his plans to formally display it.

Alexander Doyle (1857–1922) was an American sculptor.

William Harold Nungesser is an American politician serving as the 54th lieutenant governor of Louisiana since 2016. A member of the Republican Party, Nungesser is also the former president of the Plaquemines Parish Commission, having been re-elected to a second four-year term in the 2010 general election in which he topped two opponents with more than 71 percent of the vote. His second term as parish president began on January 1, 2011, and ended four years later.

The Battle of Liberty Place, or Battle of Canal Street, was an attempted insurrection and coup d'etat by the Crescent City White League against the Reconstruction Era Louisiana Republican state government on September 14, 1874, in New Orleans, which was the capital of Louisiana at the time. Five thousand members of the White League, a paramilitary terrorist organization made up largely of Confederate veterans, fought against the outnumbered New Orleans Metropolitan Police and state militia. The insurgents held the statehouse, armory, and downtown for three days, retreating before arrival of federal troops that restored the elected government. At least 32 people, including at least 21 members of the White League, were killed in the fighting. No insurgents were charged in the action.

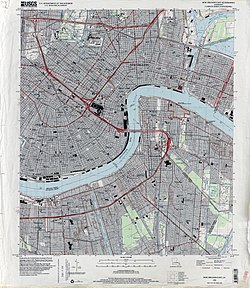

Tivoli Circle is a central traffic circle in New Orleans, Louisiana, which featured a monument to Confederate General Robert E. Lee between 1884 and 2017. During this time the circle was known as Lee Circle until its name reverted to Tivoli Circle in 2022. The inner grass circle around the monument was renamed Harmony Circle at that time.

The General Beauregard Equestrian Statue, honoring P. G. T. Beauregard, was located in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. The statue, by Alexander Doyle, one of the premier American sculptors, was officially unveiled in 1915.

Confederate monuments and memorials in the United States include public displays and symbols of the Confederate States of America (CSA), Confederate leaders, or Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War. Many monuments and memorials have been or will be removed under great controversy. Part of the commemoration of the American Civil War, these symbols include monuments and statues, flags, holidays and other observances, and the names of schools, roads, parks, bridges, buildings, counties, cities, lakes, dams, military bases, and other public structures. In a December 2018 special report, Smithsonian Magazine stated, "over the past ten years, taxpayers have directed at least $40 million to Confederate monuments—statues, homes, parks, museums, libraries, and cemeteries—and to Confederate heritage organizations."

The Robert E. Lee Monument was an outdoor bronze equestrian statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee and his horse Traveller located in Charlottesville, Virginia's Market Street Park in the Charlottesville and Albemarle County Courthouse Historic District. The statue was commissioned in 1917 and dedicated in 1924, and in 1997 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was removed on July 10, 2021, and melted down in 2023.

The Robert E. Lee Monument in Richmond, Virginia, was the first installation on Monument Avenue in 1890, and would ultimately be the last Confederate monument removed from the site. Before its removal on September 8, 2021, the monument honored Confederate Civil War General Robert E. Lee, depicted on a horse atop a large marble base that stood over 60 feet (18 m) tall. Constructed in France and shipped to Virginia, it remained the largest installation on Monument Avenue for over a century; it was first listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007 and the Virginia Landmarks Register in 2006.

The Jefferson Davis Monument, also known as the Jefferson Davis Memorial, was an outdoor sculpture and memorial to Jefferson Davis, installed at Jeff Davis Parkway and Canal Street in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States from 1911 to 2017.

The Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee Monument, often referred to simply as the Jackson and Lee Monument or Lee and Jackson Monument, was a double equestrian statue of Confederate generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, formerly located on the west side of the Wyman Park Dell in Charles Village in Baltimore, Maryland, alongside a forested hill, similar to the topography of Chancellorsville, Virginia, where Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee met before the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. The statue was removed on August 16, 2017, on the order of Baltimore City Council, but the base still remains. The monument is in storage and some city council members have called for all Confederate monuments in the state to be destroyed.

The Battle of Liberty Place Monument is a stone obelisk on an inscribed plinth, formerly on display in New Orleans, in the U.S. state of Louisiana, commemorating the "Battle of Liberty Place", an 1874 attempt by Democratic White League paramilitary organizations to take control of the government of Louisiana from its Reconstruction Era Republican leadership after a disputed gubernatorial election.

There are more than 160 monuments and memorials to the Confederate States of America and associated figures that have been removed from public spaces in the United States, all but five of which have been since 2015. Some have been removed by state and local governments; others have been torn down by protestors.