The Royal Corps of Colonial Troops (Italian : Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali or RCTC) was a corps of the Royal Italian Army, in which all the Italian colonial troops were grouped until the end of World War II in North Africa campaign.

The Royal Corps of Colonial Troops (Italian : Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali or RCTC) was a corps of the Royal Italian Army, in which all the Italian colonial troops were grouped until the end of World War II in North Africa campaign.

Many of the Askaris in Eritrea were drawn from local Nilotic populations, including Hamid Idris Awate, who reputedly had some Nara ancestry. [1] Of these troops, the first Eritrean battalions were raised in 1888 from Muslim and Christian volunteers, replacing an earlier Bashi-bazouk corps of irregulars. The four Indigeni battalions in existence by 1891 were incorporated into the Royal Corps of Colonial Troops that year. Expanded to eight battalions, the Eritrean Ascaris fought with distinction at Serobeti, Agordat, Kassala, Coatit and Adwa [2] and subsequently served in Libya and Ethiopia.

These troops were deployed on all fronts in Africa from the First Italo-Ethiopian War, the Italian-Turkish war, and the conquest of Ethiopia, until World War II. The colonial soldiers always showed courage and in some cases (like the Eritrean Ascari) fought with heroism.

Except for the German parachute division in Italy and the Japanese in Burma no enemy with whom the British and Indian troops were matched put up a finer fight than those Savoia battalions at Keren (Eritrea). Moreover, the Colonial troops, until they cracked at the very end, fought with valour and resolution, and their staunchness was a testimony to the excellence of the Italian administration and military training in Eritrea [3]

The colonial troops were commanded by Italian officers and NCOs, while soldiers were drawn from the Italian colonial territories (and to a smaller extent also from neighbouring Yemen).

In 1940, 256,000 Askaris in the Italian Royal Army were present in the local Italian colonies. Of these, 182,000 had been recruited in Italian East Africa (Eritrea, Somalia and Ethiopia) and 74,000 in Libya. In January 1941, when Allied forces invaded Italian-occupied Ethiopia in January 1941 most of the locally recruited ascaris deserted. The majority of the Eritrean Ascaris remained loyal until the Italian surrender four months later. [which surrender? discuss here.]

There were various Royal Corps of Colonial Troops:

The first two corps were united in 1935, and a year later, conquered Ethiopia was added to them, as a result of which they were all named the Forze armate dell'Africa Orientale Italiana (FF.AA. "A.O.I.", or FAAOI — Armed Forces of Italian East Africa), and remained active until 1943, when Italy was defeated in WWII. The two corps, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, were merged into a common Libyan corps, which in 1939 was renamed the Libyan corps. After 1936, the formation of colonial divisions began:

Italian Libya:

Italian East Africa:

At different times, the colonial troops of Italy consisted of irregular military units such as: bashi-buzuki, askari, savari, spahi, dubat, meharistes. Created and the so-called "gangs" (from the Italian word bande - a group), small cavalry military formations, as a rule, consisted of 100-200 people. At the same time, in North Africa, instead of horses, they used camels, more hardy to the desert area, more familiar to the Tuareg tribes.

With the occupation of Albania in 1939, colonial troops were created by the Italians there as well. They also consisted of local residents. Unlike Hitler's Nazis, who, moreover, did not yet have overseas colonies, the Italian fascists did not have a clear ideology of racial superiority, but were rather typical classical colonialists, so they tried not to destroy the local population, but exploited it. Therefore, not having a sufficient number of ethnic Italians in the colonies, to protect them, they willingly used the local people as soldiers. In turn, the natives went to the service of the Italians, because they had from this salary, rations, clothing and a relatively high status in their society.

Since the beginning of the colonial conquest the Kingdom of Italy created military units with colonial soldiers. The main units included as parts of the RCTC were:

All these military units underwent a reorganization in the 1930s, the Eritrean, Somali, and Ethiopian became the Armed Forces of Italian East Africa.

The Royal Italian Army started to modernize the colonial units in the mid-1930s. For the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935 and at the outset of World War II, it also created infantry divisions manned by colonial troops:

Other units composed mainly of colonial troops were the Libyan paratroopers Ascari del Cielo and the Italian Africa Police.

The uniforms differed between the various specialities and, to a lesser extent, in the different periods. The system of distinctive sashes was common to all the regular departments of all colonies. Each unit or branch was identifiable by the colours and motif of the wide woollen sash ("etagà") wrapped around the waist and, in the Eritrean and AOI cavalry units, wrapped around the tarbush. [8] [9] As examples, the 17th Eritrean Battalion had black and white tarbush tassels and vertically striped sashes; while the 64th Eritrean Battalion wore both of these items in scarlet and purple. The same colours were reproduced in the edging thread of the shoulder straps of the Italian officers who led the units. [10]

The ascari of Eritrea, Somalia and AOI wore the colonial uniform in white or khaki cloth with the aforementioned distinctive sashes, felt tarbush (a high red fez) with bow and frieze depending on the speciality. [11] White uniforms were initially used and later were relegated to parades with khaki being worn for other duties. Askari wore three different types of four pocket tunics; the M1929 giubba with low standing collar, the pre-1940 and M1940 camicotta Sahariano per Coloniali with stand-and-fall collars. Libyans, Ethiopians, and Eritreans wore baggy trousers while Somalis wore baggy knee length shorts. Their puttees were often worn with bare feet: in fact, respecting tradition, the shoes were optional. When present they could consist of both sandals, boots, or marching boots. Khaki covers were often worn on the tachia and tarbush when on campaign.

The Muslim ascari of East Africa (most of the colonials were Copts) wore a turban as their headdress, with a battalion-coloured diagonal band on the front. Libyan ascari and savari used, instead of tarbush, the traditional Libyan tachia (ṭaqīyā), [12] a form fitting fez, of garnet red felt with blue bow and white "sub-tachia". [13] The colours distinguished the Savari departments, in addition to the usual bands.

The Italian officers permanently assigned to colonial units wore the issue tropical peaked cap, the coloured sash of his battalion with identical piping around his shoulder boards mounted on any issue tunic. He could wear either khaki straight trousers or breeches with high brown field boots with or without lacing at the foot. [14]

The zaptié of all the colonies were distinguished by the collar frogs of the carabinieri, with the flame on the headdress and the distinctive scarlet band.

The irregular units such as the dubat, basci-buzuk, spahis and bande did not wear a standard uniform although the bande had a system of ranks of a sort.

The Ascari had the following ranks, from simple soldier to senior non-commissioned officer: Ascari - Muntaz (corporal) - Bulukbasci (lance-sergeant) -Sciumbasci (sergeant). The Sciumbasci-capos (staff-sergeants) were the senior Eritrean non-commissioned officers, chosen in part according to their performance in battle.

All commissioned officers of the Eritrean Ascari were Italian. [15]

The indigenous personnel had their own hierarchy different from that of the Royal Army, which is also the same for all RCTCs. The highest rank achievable for the natives was that of a non-commissioned officer, while the corps officers were all Italians.

The rank badges consisted of chevrons in red and yellow wool fabric, made at an angle, with the tip facing the shoulder, mounted on a pentagonal blue, later black, triangle cloth brassard, in the manner of the Ottoman Army. Libyan troops wore the same insignia until 1939 when they became officially Italians, they could also wear the Star of Savoy at this point, with another change to a modified smaller version sewn directly onto the upper arm sleeve in 1941. The grades were repeated on the tarbush with chevrons and five-pointed stars.

The grades were as follows: [16] [17]

On the black cloth triangle of the badge were also placed the marks of seniority - according to the table below - and of merit (the Savoy crown) as a promotion badge for war merit, as well as the speciality badge (machine gunner, chosen machine gunner, musician, trumpeter, tambourine, saddler, farrier, international bracelet) and the war wound badge.

| 1 red cloth star | 2 years of service |

| 2 red cloth stars | 6 years of service |

| 3 red cloth stars | 10 years of service |

| 1 silver fabric star | 12 years of service |

| 2 silver fabric stars | 14 years of service |

| 3 silver fabric stars | 15 years of service |

| 1 gold fabric star | 20 years of service |

| 2 gold fabric stars | 24 years of service |

| 3 gold fabric stars | 28 years of service |

The following rank table is for Askari serving in the Italian Forces.

| Rank group | Enlisted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army and Air force |  |  |  |  | | | No insignia |

| Sciumbasci capo | Sciumbasci | Bulucbasci capo | bulucbasci | Muntaz | Uachil | Ascaro | |

| Navy and Carabinieri |  |  |  |  | | | No insignia |

| Sciumbasci capo | Sciumbasci | Bulucbasci capo | bulucbasci | Muntaz | Uachil | Ascaro | |

The Italian colonial forces were armed with older model weapons, mainly produced in Italy itself, or captured, but by the beginning of World War II, they were clearly outdated.

Since the 20s, the following armored vehicles were transferred to Libya;

Colonial units were primarily equipped with light artillery and mortars

The Royal Corps of Colonial Troops has been awarded 4 Gold Medals of Military Valor ("Medaglia d'oro al valor militare"):

Two Gold Medal of Military Valor:

![]() In one hundred and fifty battles gloriously sustained in the service of His Majesty the King of Italy, gave constant evidence of strong heroic military discipline, of fierce warrior spirit, of unquestioned loyalty and value, lavishing their blood with a zeal and devotion than never had limitations. Eritrea - Tripoli - Cyrenaica, from 1889 to 1929. - May 12, 1930 [30]

In one hundred and fifty battles gloriously sustained in the service of His Majesty the King of Italy, gave constant evidence of strong heroic military discipline, of fierce warrior spirit, of unquestioned loyalty and value, lavishing their blood with a zeal and devotion than never had limitations. Eritrea - Tripoli - Cyrenaica, from 1889 to 1929. - May 12, 1930 [30]

![]() With the courage of their race, fueled by love for the flag and the belief in the higher destinies of Italy in Africa, gave during the war, many proofs of the most brilliant heroism. With great generosity, and similar faithfulness, gave their blood for the consecration of the Italian Empire. Italo-Ethiopian War, October 3, 1935 - May 5, 1936. - November 19, 1936. [31]

With the courage of their race, fueled by love for the flag and the belief in the higher destinies of Italy in Africa, gave during the war, many proofs of the most brilliant heroism. With great generosity, and similar faithfulness, gave their blood for the consecration of the Italian Empire. Italo-Ethiopian War, October 3, 1935 - May 5, 1936. - November 19, 1936. [31]

One Gold Medal of Military Valor:

![]() With the courage of their race - fueled by love for the flag and the belief in the higher destinies of Italy in Africa, gave during the war, many proofs of the most brilliant heroism. With great generosity, and similar faithfulness, gave their blood for the consecration of the Italian Empire. Italo-Ethiopian War, October 3, 1935 - May 5, 1936. - November 19, 1936. [32]

With the courage of their race - fueled by love for the flag and the belief in the higher destinies of Italy in Africa, gave during the war, many proofs of the most brilliant heroism. With great generosity, and similar faithfulness, gave their blood for the consecration of the Italian Empire. Italo-Ethiopian War, October 3, 1935 - May 5, 1936. - November 19, 1936. [32]

One Gold Medal of Military Valor:

![]() With the courage of their race - fueled by love for the flag and the belief in the higher destinies of Italy in Africa, gave during the war, many proofs of the most brilliant heroism. With great generosity, and similar faithfulness, gave their blood for the consecration of the Italian Empire. Italo-Ethiopian War, October 3, 1935 - May 5, 1936. - November 19, 1936. [33]

With the courage of their race - fueled by love for the flag and the belief in the higher destinies of Italy in Africa, gave during the war, many proofs of the most brilliant heroism. With great generosity, and similar faithfulness, gave their blood for the consecration of the Italian Empire. Italo-Ethiopian War, October 3, 1935 - May 5, 1936. - November 19, 1936. [33]

Italian Somaliland was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th century by the Somali Sultanates of Hobyo and Majeerteen in the north, and in the south by political entities such as the Hiraab Imamate and Geledi Sultanate.

An askari or ascari was a local soldier serving in the armies of the European colonial powers in Africa, particularly in the African Great Lakes, Northeast Africa and Central Africa. The word is used in this sense in English, as well as in German, Italian, Urdu, and Portuguese. In French, the word is used only in reference to native troops outside the French colonial empire. The designation is still in occasional use today to informally describe police, gendarmerie and security guards.

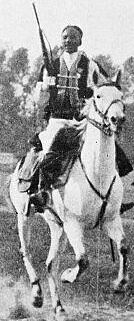

Savari was the designation given to the regular native Libyan cavalry regiments of the Italian colonial army from 1912 to 1943, in Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica, and later in Italian Libya. The word "savari" was derived from a Persian term for "horsemen" (Savārān).

Olol Dinle was a Somali sultan who ruled Kelafo as the head of the Ajuran. He successively offered allegiance to the Kingdom of Italy in the 1920s and was named "Sultan of Sciavelli (Shabelle) and Auia (Hawiye)" in the early 1930s.

The Italian order of battle for the Second Italo-Ethiopian War on 8 October 1935. The Ethiopian order of battle is listed separately.

Zaptié was the designation given to locally raised gendarmerie units in the Italian colonies of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, Eritrea and Somaliland between 1889 and 1943.

Dubat ; Arabic:العمائم البيضاء ); ḍubbāṭ: English: White turban) was the designation given to members of the semi-regular armed bands employed by the Italian "Royal Corps of Colonial Troops" in Italian Somaliland from 1924 to 1941. The word dubat was derived from a Somali phrase meaning "white turban".

The Libyan Division was a formation of colonial troops raised by the Italians in their colony in Libya. It participated in the invasion of Ethiopia in the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. The formation was reorganized into the 1st Libyan Division by the beginning of Italy's entry into World War II. In September 1940, the 1st Libyan Division, together with its sister-division 2nd Libyan Division, participated in the Italian invasion of Egypt. By December, the division was dug in at Maktila and was forced to surrender during Operation Compass.

The Italian African Police, was the provost, and police force of Italian North Africa and Italian East Africa from 1 June 1936 to 1 December 1945.

Italian Eritreans are Eritrean-born citizens who are fully or partially of Italian descent, whose ancestors were Italians who emigrated to Eritrea during the Italian diaspora, or Italian-born people in Eritrea.

The Royal Corps Of Eritrean Colonial Troops were indigenous soldiers from Eritrea, who were enrolled as askaris in the Royal Corps of Colonial Troops of the Royal Italian Army during the period 1889–1941.

Bands was an Italian military term for irregular forces, composed of natives, with Italian officers and NCOs in command. These units were employed by the Italian Army as auxiliaries to the regular national and colonial military forces. They were also known to the British colonial forces as "armed Bands".

The muntaz was a military rank of the Italian colonial troops, equivalent to the rank of corporal in the Italian Royal Army Regio Esercito.

Italian Eritrea was a colony of the Kingdom of Italy in the territory of present-day Eritrea. The first Italian establishment in the area was the purchase of Assab by the Rubattino Shipping Company in 1869, which came under government control in 1882. Occupation of Massawa in 1885 and the subsequent expansion of territory would gradually engulf the region and in 1889 the Ethiopian Empire recognized the Italian possession in the Treaty of Wuchale. In 1890 the Colony of Eritrea was officially founded.

The Cacciatori d'Africa were Italian light infantry and mounted infantry units raised for colonial service in Africa. Cacciatori units later served in Somalia, Eritrea, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica for the Italian colonial empire. Partially mechanised in the early 1920s, the Cacciatori d'Africa remained part of the Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali until 1942.

Italian Spahis were light cavalry colonial troops of the Kingdom of Italy, raised in Italian Libya between 1912 and 1942.

The Royal Corps of Somali Colonial Troops was the colonial body of the Royal Italian Army based in Italian Somaliland, in present-day northeastern, central and southern Somalia.

The Italian colonial railways started with the opening in 1888 of a short section of line in Italian Eritrea, and ended in 1943 with the loss of Italian Libya after the Allied offensive in North Africa and the destruction of the railways around Italian Tripoli. The colonial railways of the Kingdom of Italy reached 1,561 kilometres (970 mi) before WWII.

Domenico Turitto was an Italian major who was part of the Royal Colonial Corps of Eritrea. He participated in the Mahdist War as he commanded the 1st Indigenous Infantry Battalion, occupying the city of Kassala and distinguishing himself at the Battle of Kassala. During the First Italo-Ethiopian War, Turitto commanded the vanguard of the Indigenous brigade under the command of Matteo Albertone before being killed in the battle. He was also a recipient of the Silver and Bronze Medals of Military Valor and a knight of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus.

The Commemorative Medal of the African Campaigns was a decoration established in 1894 by the Kingdom of Italy for personnel who took part in Italian military operations in Africa between 1887 and 1896 as the Italian Empire began its expansion during the Scramble for Africa. As the Italian Empire expanded in East Africa, the medal's applicability was extended in 1906 and 1923 to include additional service in the region.