A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and recognize further and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future.

Measles is a highly contagious, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than 40 °C (104 °F), cough, runny nose, and inflamed eyes. Small white spots known as Koplik's spots may form inside the mouth two or three days after the start of symptoms. A red, flat rash which usually starts on the face and then spreads to the rest of the body typically begins three to five days after the start of symptoms. Common complications include diarrhea, middle ear infection (7%), and pneumonia (6%). These occur in part due to measles-induced immunosuppression. Less commonly seizures, blindness, or inflammation of the brain may occur. Other names include morbilli, rubeola, red measles, and English measles. Both rubella, also known as German measles, and roseola are different diseases caused by unrelated viruses.

Mumps is a highly contagious viral disease caused by the mumps virus. Initial symptoms of mumps are non-specific and include fever, headache, malaise, muscle pain, and loss of appetite. These symptoms are usually followed by painful swelling around the side of the face, which is the most common symptom of a mumps infection. Symptoms typically occur 16 to 18 days after exposure to the virus. About one third of people with a mumps infection do not have any symptoms (asymptomatic).

The MMR vaccine is a vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella, abbreviated as MMR. The first dose is generally given to children around 9 months to 15 months of age, with a second dose at 15 months to 6 years of age, with at least four weeks between the doses. After two doses, 97% of people are protected against measles, 88% against mumps, and at least 97% against rubella. The vaccine is also recommended for those who do not have evidence of immunity, those with well-controlled HIV/AIDS, and within 72 hours of exposure to measles among those who are incompletely immunized. It is given by injection.

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and last for three days. It usually starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body. The rash is sometimes itchy and is not as bright as that of measles. Swollen lymph nodes are common and may last a few weeks. A fever, sore throat, and fatigue may also occur. Joint pain is common in adults. Complications may include bleeding problems, testicular swelling, encephalitis, and inflammation of nerves. Infection during early pregnancy may result in a miscarriage or a child born with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Symptoms of CRS manifest as problems with the eyes such as cataracts, deafness, as well as affecting the heart and brain. Problems are rare after the 20th week of pregnancy.

Immunization, or immunisation, is the process by which an individual's immune system becomes fortified against an infectious agent.

The Wistar Institute is an independent, nonprofit research institution in biomedical science with special focuses in oncology, immunology, infectious disease and vaccine research. Located on Spruce Street in Philadelphia’s University City neighborhood, Wistar was founded in 1892 as a nonprofit institution to focus on biomedical research and training.

A vaccination schedule is a series of vaccinations, including the timing of all doses, which may be either recommended or compulsory, depending on the country of residence. A vaccine is an antigenic preparation used to produce active immunity to a disease, in order to prevent or reduce the effects of infection by any natural or "wild" pathogen. Vaccines go through multiple phases of trials to ensure safety and effectiveness.

The schedule for childhood immunizations in the United States is published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The vaccination schedule is broken down by age: birth to six years of age, seven to eighteen, and adults nineteen and older. Childhood immunizations are key in preventing diseases with epidemic potential.

The MMRV vaccine combines the attenuated virus MMR vaccine with the addition of the varicella (chickenpox) vaccine. The MMRV vaccine is typically given to children between one and two years of age.

Mumps vaccines are vaccines which prevent mumps. When given to a majority of the population they decrease complications at the population level. Effectiveness when 90% of a population is vaccinated is estimated at 85%. Two doses are required for long term prevention. The initial dose is recommended between 12 and 18 months of age. The second dose is then typically given between two years and six years of age. Usage after exposure in those not already immune may be useful.

A breakthrough infection is a case of illness in which a vaccinated individual becomes infected with the illness, because the vaccine has failed to provide complete immunity against the pathogen. Breakthrough infections have been identified in individuals immunized against a variety of diseases including mumps, varicella (Chickenpox), influenza, and COVID-19. The characteristics of the breakthrough infection are dependent on the virus itself. Often, infection of the vaccinated individual results in milder symptoms and shorter duration than if the infection were contracted naturally.

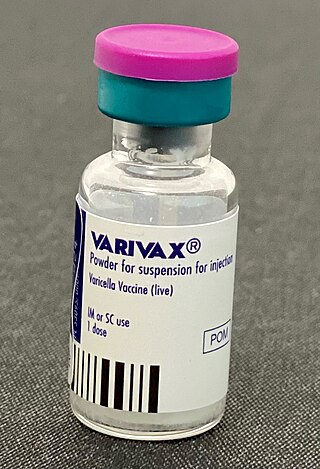

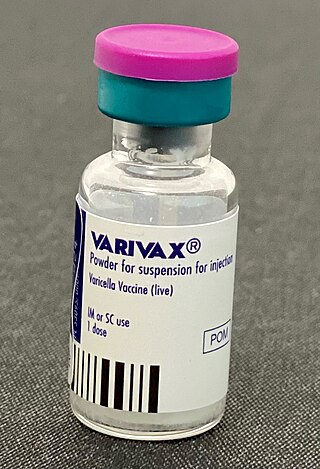

Varicella vaccine, also known as chickenpox vaccine, is a vaccine that protects against chickenpox. One dose of vaccine prevents 95% of moderate disease and 100% of severe disease. Two doses of vaccine are more effective than one. If given to those who are not immune within five days of exposure to chickenpox it prevents most cases of disease. Vaccinating a large portion of the population also protects those who are not vaccinated. It is given by injection just under the skin. Another vaccine, known as zoster vaccine, is used to prevent diseases caused by the same virus – the varicella zoster virus.

Immunization during pregnancy is the administration of a vaccine to a pregnant individual. This may be done either to protect the individual from disease or to induce an antibody response, such that the antibodies cross the placenta and provide passive immunity to the infant after birth. In many countries, including the US, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand, vaccination against influenza, COVID-19 and whooping cough is routinely offered during pregnancy.

An attenuated vaccine is a vaccine created by reducing the virulence of a pathogen, but still keeping it viable. Attenuation takes an infectious agent and alters it so that it becomes harmless or less virulent. These vaccines contrast to those produced by "killing" the pathogen.

Hepatitis A vaccine is a vaccine that prevents hepatitis A. It is effective in around 95% of cases and lasts for at least twenty years and possibly a person's entire life. If given, two doses are recommended beginning after the age of one. It is given by injection into a muscle. The first hepatitis A vaccine was approved in Europe in 1991, and the United States in 1995. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.

Claims of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism have been extensively investigated and found to be false. The link was first suggested in the early 1990s and came to public notice largely as a result of the 1998 Lancet MMR autism fraud, characterised as "perhaps the most damaging medical hoax of the last 100 years". The fraudulent research paper, authored by discredited former doctor Andrew Wakefield and published in The Lancet, falsely claimed the vaccine was linked to colitis and autism spectrum disorders. The paper was retracted in 2010 but is still cited by anti-vaccine activists.

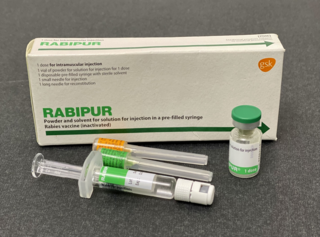

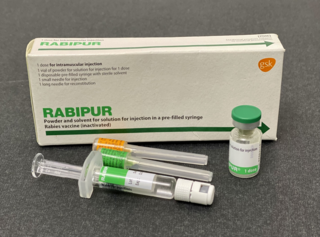

The rabies vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent rabies. There are several rabies vaccines available that are both safe and effective. Vaccinations must be administered prior to rabies virus exposure or within the latent period after exposure to prevent the disease. Transmission of rabies virus to humans typically occurs through a bite or scratch from an infectious animal, but exposure can occur through indirect contact with the saliva from an infectious individual.

Measles vaccine protects against becoming infected with measles. Nearly all of those who do not develop immunity after a single dose develop it after a second dose. When the rate of vaccination within a population is greater than 92%, outbreaks of measles typically no longer occur; however, they may occur again if the rate of vaccination decreases. The vaccine's effectiveness lasts many years. It is unclear if it becomes less effective over time. The vaccine may also protect against measles if given within a couple of days after exposure to measles.

Japanese encephalitis vaccine is a vaccine that protects against Japanese encephalitis. The vaccines are more than 90% effective. The duration of protection with the vaccine is not clear but its effectiveness appears to decrease over time. Doses are given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.