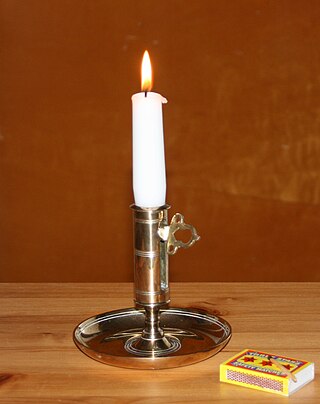

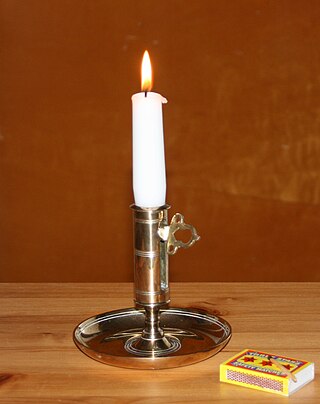

A candle is an ignitable wick embedded in wax, or another flammable solid substance such as tallow, that provides light, and in some cases, a fragrance. A candle can also provide heat or a method of keeping time.

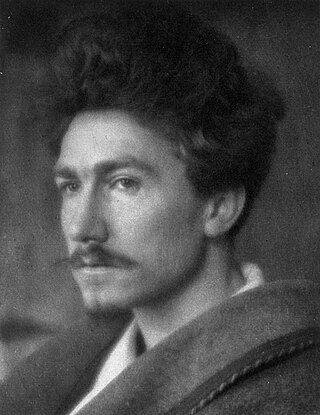

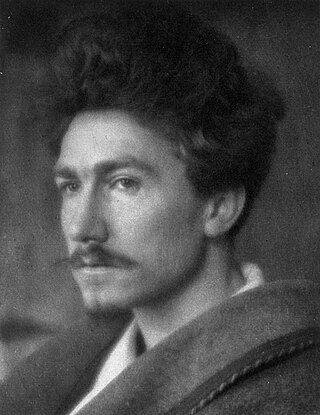

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a collaborator in Fascist Italy and the Salò Republic during World War II. His works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his 800-page epic poem, The Cantos.

Stage lighting is the craft of lighting as it applies to the production of theater, dance, opera, and other performance arts. Several different types of stage lighting instruments are used in this discipline. In addition to basic lighting, modern stage lighting can also include special effects, such as lasers and fog machines. People who work on stage lighting are commonly referred to as lighting technicians or lighting designers.

Pemmican is a mixture of tallow, dried meat, and sometimes dried berries. A calorie-rich food, it can be used as a key component in prepared meals or eaten raw. Historically, it was an important part of indigenous cuisine in certain parts of North America and it is still prepared today. The word comes from the Cree word ᐱᒦᐦᑳᓐ, which is derived from the word ᐱᒥᕀ, "fat, grease". The Lakota word is wasná, originally meaning "grease derived from marrow bones", with the wa- creating a noun, and sná referring to small pieces that adhere to something. It was invented by the Indigenous peoples of North America.

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton fat, primarily made up of triglycerides.

Pith, or medulla, is a tissue in the stems of vascular plants. Pith is composed of soft, spongy parenchyma cells, which in some cases can store starch. In eudicotyledons, pith is located in the center of the stem. In monocotyledons, it extends also into flowering stems and roots. The pith is encircled by a ring of xylem; the xylem, in turn, is encircled by a ring of phloem.

Juncaceae is a family of flowering plants, commonly known as the rush family. It consists of 8 genera and about 464 known species of slow-growing, rhizomatous, herbaceous monocotyledonous plants that may superficially resemble grasses and sedges. They often grow on infertile soils in a wide range of moisture conditions. The best-known and largest genus is Juncus. Most of the Juncus species grow exclusively in wetland habitats. A few rushes, such as Juncus bufonius are annuals, but most are perennials.

Rendering is a process that converts waste animal tissue into stable, usable materials. Rendering can refer to any processing of animal products into more useful materials, or, more narrowly, to the rendering of whole animal fatty tissue into purified fats like lard or tallow. Rendering can be carried out on an industrial, farm, or kitchen scale. It can also be applied to non-animal products that are rendered down to pulp. The rendering process simultaneously dries the material and separates the fat from the bone and protein, yielding a fat commodity and a protein meal.

A votive candle or prayer candle is a small candle, typically white or beeswax yellow, intended to be burnt as a votive offering in an act of Christian prayer, especially within the Anglican, Lutheran, and Roman Catholic Christian denominations, among others. In Christianity, votive candles are commonplace in many churches, as well as home altars, and symbolize the "prayers the worshipper is offering for him or herself, or for other people." The size of a votive candle is often two inches tall by one and a half inches diameter, although other votive candles can be significantly taller and wider. In other religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, similar offerings exist, which include diyas and butter lamps.

The Cantos by Ezra Pound is a long, incomplete poem in 120 sections, each of which is a canto. Most of it was written between 1915 and 1962, although much of the early work was abandoned and the early cantos, as finally published, date from 1922 onwards. It is a book-length work, widely considered to present formidable difficulties to the reader. Strong claims have been made for it as the most significant work of modernist poetry of the twentieth century. As in Pound's prose writing, the themes of economics, governance and culture are integral to its content.

Juncus effusus is a perennial herbaceous flowering plant species in the rush family Juncaceae, with the common names common rush or soft rush. In North America, the common name soft rush also refers to Juncus interior.

A light fixture, light fitting, or luminaire is an electrical device containing an electric lamp that provides illumination. All light fixtures have a fixture body and one or more lamps. The lamps may be in sockets for easy replacement—or, in the case of some LED fixtures, hard-wired in place.

Candle making was developed independently in many places around the world.

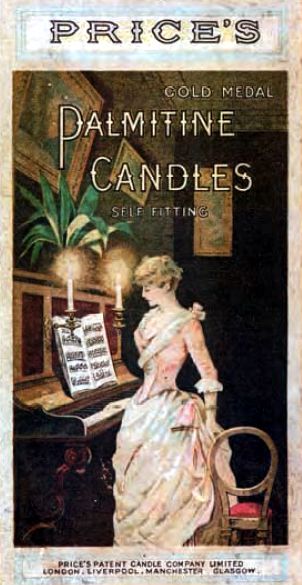

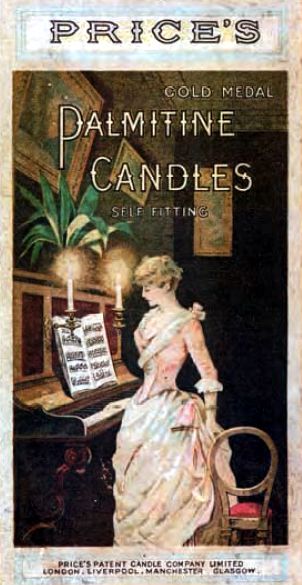

Price's Patent Candles, founded in 1830, is an importer and retailer of candles. The firm is headquartered in Bedford in England, and holds the royal warrant of appointment for the supply of candles. It is today the largest candle supplier in the United Kingdom, and the company holds an important place in the technological history of candle making.

A candelabra or candelabrum is a candle holder with multiple arms.

The Betty lamp is a lamp thought to be of German, Austrian, or Hungarian origin. It came into use in the 18th century. They were commonly made of iron or brass and were most often used in the home or workshop. These lamps burned fish oil or fat trimmings and had wicks of twisted cloth.

The Hindenburg light or Hindenburglicht, was a source of tallow lighting used in the trenches of the First World War, named after the Commander-in-Chief of the German army in World War I, Paul von Hindenburg. It was a flat bowl approximately 5–8 cm (2.0–3.1 in) diameter and 1–1.5 cm (0.39–0.59 in) deep, resembling the cover of Mason jar lid (Schraubglasdeckel) and made from pasteboard. This flat bowl was filled with a wax-like fat (tallow). A short wick (Docht) in the center was lit and burned for some hours. A later model of the Hindenburglicht was a "tin can (Dosenlicht) lamp." Here, a wax-filled tin can have two wicks in a holder. If both wicks are lit, a common, broad flame results.

A tealight is a candle in a thin metal or plastic cup so that the candle can liquefy completely while lit. They are typically small, circular, usually wider than their height, and inexpensive. Tealights derive their name from their use in teapot warmers, but are also used as food warmers in general, e.g. fondue.

Charles Domery, later also known as Charles Domerz, was a Polish soldier serving in the Prussian and French armies, noted for his unusually large appetite. Serving in the Prussian Army against France during the War of the First Coalition, he found that the rations of the Prussians were insufficient and deserted to the French Army in return for food. Although generally healthy, he was voraciously hungry during his time in the French service, and ate any available food. While stationed near Paris, he was recorded as having eaten 174 cats in a year, and although he disliked vegetables, he would eat 4 to 5 pounds of grass each day if he could not find other food. During service on the French ship Hoche, he attempted to eat the severed leg of a crew member hit by cannon fire, before other members of the crew wrestled it from him.

A luchina is a long thin sliver/chip or plate of wood, most commonly used as a miniature torch for makeshift lighting of the interiors of buildings in the history of Russia. Similar implements were used in other countries, e.g., Poland, Ukraine.