Related Research Articles

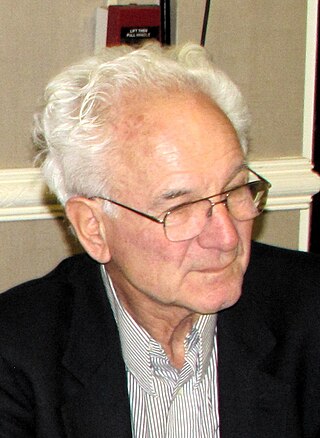

Peter H. Duesberg is a German-American molecular biologist and a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is known for his early research into the genetic aspects of cancer. He is a proponent of AIDS denialism, the claim that HIV does not cause AIDS.

Scientific misconduct is the violation of the standard codes of scholarly conduct and ethical behavior in the publication of professional scientific research.

HIV/AIDS denialism is the belief, despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) does not cause acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Some of its proponents reject the existence of HIV, while others accept that HIV exists but argue that it is a harmless passenger virus and not the cause of AIDS. Insofar as they acknowledge AIDS as a real disease, they attribute it to some combination of sexual behavior, recreational drugs, malnutrition, poor sanitation, haemophilia, or the effects of the medications used to treat HIV infection (antiretrovirals).

The Lancet is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

In academic publishing, a retraction is a mechanism by which a published paper in an academic journal is flagged for being seriously flawed to the extent that their results and conclusions can no longer be relied upon. Retracted articles are not removed from the published literature but marked as retracted. In some cases it may be necessary to remove an article from publication, such as when the article is clearly defamatory, violates personal privacy, is the subject of a court order, or might pose a serious health risk to the general public.

Luc Montagnier was a French virologist and joint recipient, with Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Harald zur Hausen, of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). He worked as a researcher at the Pasteur Institute in Paris and as a full-time professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China.

The Royal Free Hospital is a major teaching hospital in the Hampstead area of the London Borough of Camden. The hospital is part of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, which also runs services at Barnet Hospital, Chase Farm Hospital and a number of other sites. The trust is a founder member of the UCLPartners academic health science centre.

Brian Deer is a British investigative journalist, best known for inquiries into the drug industry, medicine and social issues for The Sunday Times. Deer's investigative nonfiction book The Doctor Who Fooled the World, an exposé on disgraced former doctor Andrew Wakefield and the 1998 Lancet MMR autism fraud was published in September 2020 by Johns Hopkins University Press.

False balance, known colloquially as bothsidesism, is a media bias in which journalists present an issue as being more balanced between opposing viewpoints than the evidence supports. Journalists may present evidence and arguments out of proportion to the actual evidence for each side, or may omit information that would establish one side's claims as baseless. False balance has been cited as a cause of misinformation.

Patrick Holford is a British author and entrepreneur who endorses a range of controversial vitamin tablets. As an advocate of alternative nutrition and diet methods, he appears regularly on television and radio in the UK and abroad. He has 36 books in print in 29 languages. His business career promotes a wide variety of alternative medical approaches such as orthomolecular medicine, many of which are considered pseudoscientific by mainstream science and medicine.

Claims of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism have been extensively investigated and found to be false. The link was first suggested in the early 1990s and came to public notice largely as a result of the 1998 Lancet MMR autism fraud, characterised as "perhaps the most damaging medical hoax of the last 100 years". The fraudulent research paper authored by Andrew Wakefield and published in The Lancet falsely claimed the vaccine was linked to colitis and autism spectrum disorders. The paper was retracted in 2010 but is still cited by anti-vaxxers.

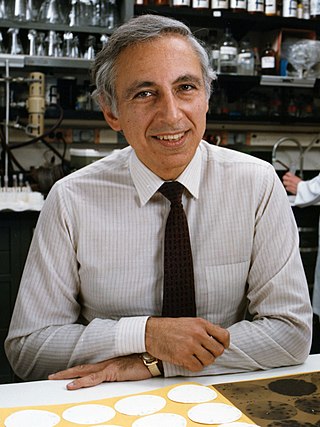

Robert Charles Gallo is an American biomedical researcher. He is best known for his role in establishing the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the infectious agent responsible for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and in the development of the HIV blood test, and he has been a major contributor to subsequent HIV research.

Andrew Jeremy Wakefield is a British anti-vaccine activist, former physician, and discredited academic who was struck off the medical register for his involvement in The Lancet MMR autism fraud, a 1998 study that fraudulently claimed a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism. He has subsequently become known for anti-vaccination activism. Publicity around the 1998 study caused a sharp decline in vaccination uptake, leading to a number of outbreaks of measles around the world. He was a surgeon on the liver transplant programme at the Royal Free Hospital in London and became senior lecturer and honorary consultant in experimental gastroenterology at the Royal Free and University College School of Medicine. He resigned from his positions there in 2001, "by mutual agreement", then moved to the United States. In 2004, Wakefield co-founded and began working at the Thoughtful House research center in Austin, Texas, serving as executive director there until February 2010, when he resigned in the wake of findings against him by the British General Medical Council.

In scientific publishing, the 1969 Ingelfinger rule originally stipulated that The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) would not publish findings that had been published elsewhere, in other media or in other journals. The rule was subsequently adopted by several other scientific journals, and has shaped scientific publishing ever since. Historically it has also helped to ensure that the journal's content is fresh and does not duplicate content previously reported elsewhere, and seeks to protect the scientific embargo system.

The Séralini affair was the controversy surrounding the publication, retraction, and republication of a journal article by French molecular biologist Gilles-Éric Séralini. First published by Food and Chemical Toxicology in September 2012, the article presented a two-year feeding study in rats, and reported an increase in tumors among rats fed genetically modified corn and the herbicide RoundUp. Scientists and regulatory agencies subsequently concluded that the study's design was flawed and its findings unsubstantiated. A chief criticism was that each part of the study had too few rats to obtain statistically useful data, particularly because the strain of rat used, Sprague Dawley, develops tumors at a high rate over its lifetime.

Gilles-Éric Séralini is a French molecular biologist, political advisor and activist on genetically modified organisms and foods. He is of Algerian-French origin. Séralini has been a professor of molecular biology at the University of Caen since 1991, and is president and chairman of the board of CRIIGEN.

Vijendra Kumar Singh is a neuroimmunologist who formerly held a post at Utah State University, prior to which he was a professor at the University of Michigan. While affiliated with both institutions, he conducted some controversial autism-related research focusing on the potential role of immune system disorders in the etiology of autism. For example, he has testified before a US congressional committee that, in his view, "three quarters of autistic children suffer from an autoimmune disease."

The Lancet MMR autism fraud centered on the publication in February 1998 of a fraudulent research paper titled "Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children" in The Lancet. The paper, authored by now discredited and deregistered Andrew Wakefield, and twelve coauthors, falsely claimed causative links between the MMR vaccine and colitis and between colitis and autism. The fraud was exposed in a lengthy Sunday Times investigation by reporter Brian Deer, resulting in the paper's retraction in February 2010 and Wakefield being struck off the UK medical register three months later. Wakefield reportedly stood to earn up to $43 million per year selling diagnostic kits for a non-existent syndrome he claimed to have discovered. He also held a patent to a rival vaccine at the time, and he had been employed by a lawyer representing parents in lawsuits against vaccine producers.

Extensive investigation into vaccines and autism spectrum disorder has shown that there is no relationship between the two, causal or otherwise, and that the vaccine ingredients do not cause autism. Vaccinologist Peter Hotez researched the growth of the false claim and concluded that its spread originated with Andrew Wakefield's fraudulent 1998 paper, with no prior paper supporting a link.

JABS is a British pressure group launched in Wigan in January 1994. Beginning as a support group for the parents of children they claim became ill after the MMR vaccine, the group is currently against all forms of vaccination.

References

- ↑ Jerome, F (July 1989). "Science by press conference". Technology Review (92): 72–73.

- ↑ Hall, Stephen S. (2004). Merchants of Immortality: Chasing the Dream of Human Life Extension. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-49221-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moore Andrew (2006). "Bad science in the headlines: Who takes responsibility when science is distorted in the mass media?". EMBO Reports . 7 (12): 1193–1196. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400862. PMC 1794697 . PMID 17139292.

- ↑ Andreopoulos Spyros (March 27, 1980). Gene Cloning by Press Conference. N Engl J Med 1980; 302:743–746

- 1 2 Hall, Stephen K. (2003). Merchants of immortality: chasing the dream of human life extension . Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-49221-3.

- 1 2 Angell, Marcia; Kassirer, Jerome P. (1991). "The Ingelfinger Rule Revisited". New England Journal of Medicine. 325 (19): 1371–1373. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111073251910 . PMID 1669838.

- ↑ Wilford, John Noble (April 24, 1989). Fusion Furor: Science's Human Face. New York Times

- ↑ Lewenstein, Bruce V. (1992). Cold Fusion and Hot History. Osiris, 2nd series, 7, 135–163.

- ↑ Godlee, F; Smith, J.; Marcovitch, H. (2011). "Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent". BMJ . 342: c7452. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7452. PMID 21209060. S2CID 43640126.

- ↑ "Study linking vaccine to autism was fraud". NPR. Associated Press. 2011-01-05. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- ↑ Rose, David (2010-02-03). "Lancet journal retracts Andrew Wakefield MMR scare paper". Times Online. London. Archived from the original on 2011-04-10.

- ↑ Löfstedt, Ragnar (October 2008). "Risk communication, media amplification and the aspartame scare". Risk Management. 10 (4): 257–284. doi:10.1057/rm.2008.11. S2CID 189839927.

- ↑ Butler, Declan (2012). "Hyped GM maize study faces growing scrutiny". Nature. 490 (7419): 158. Bibcode:2012Natur.490..158B. doi: 10.1038/490158a . PMID 23060167.

- ↑ "Elsevier Announces Article Retraction from Journal Food and Chemical Toxicology". Elsevier. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- 1 2 3 J A Winsten (1985). "Science and the media: the boundaries of truth". Health Affairs . 4 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.4.1.5. PMID 3997047.

- ↑ Rödder, Simone; Franzen, Martina; Weingart, Peter, eds. (2012). The sciences' media connection : public communication and its repercussions. Dordrecht/New York: Springer. ISBN 978-9400720848.

- ↑ Kalichman, Seth C. (2009). Denying AIDS: Conspiracy Theories, Pseudoscience, and Human Tragedy. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-79475-4 . Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ↑ Wilcox RA, Djulbegovic B, Moffitt HL, Guyatt GH, Montori VM (January 2008). "Randomized trials in oncology stopped early for benefit". J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (1): 18–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6259 . PMID 18165635.