Gallaudet University is a private federally chartered university in Washington, D.C., for the education of the deaf and hard of hearing. It was founded in 1864 as a grammar school for both deaf and blind children. It was the first school for the advanced education of the deaf and hard of hearing in the world and remains the only higher education institution in which all programs and services are specifically designed to accommodate deaf and hard of hearing students. Hearing students are admitted to the graduate school and a small number are also admitted as undergraduates each year. The university was named after Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, a notable figure in the advancement of deaf education.

French Sign Language is the sign language of the deaf in France and French-speaking parts of Switzerland. According to Ethnologue, it has 100,000 native signers.

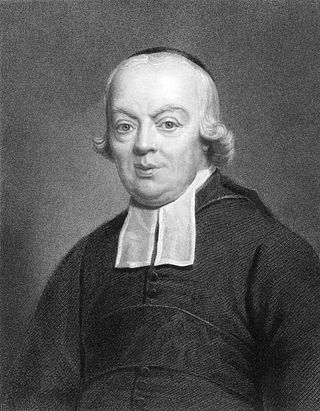

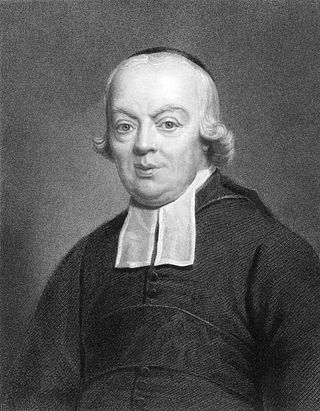

Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet was an American educator. Along with Laurent Clerc and Mason Cogswell, he co-founded the first permanent institution for the education of the deaf in North America, and he became its first principal. When opened on April 15, 1817, it was called the "Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons," but it is now known as the American School for the Deaf.

Edward Miner Gallaudet, was the first president of Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. from 1864 to 1910.

Visible Speech is a system of phonetic symbols developed by British linguist Alexander Melville Bell in 1867 to represent the position of the speech organs in articulating sounds. Bell was known internationally as a teacher of speech and proper elocution and an author of books on the subject. The system is composed of symbols that show the position and movement of the throat, tongue, and lips as they produce the sounds of language, and it is a type of phonetic notation. The system was used to aid the deaf in learning to speak.

Oralism is the education of deaf students through oral language by using lip reading, speech, and mimicking the mouth shapes and breathing patterns of speech. Oralism came into popular use in the United States around the late 1860s. In 1867, the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts, was the first school to start teaching in this manner. Oralism and its contrast, manualism, manifest differently in deaf education and are a source of controversy for involved communities. Listening and Spoken Language, a technique for teaching deaf children that emphasizes the child's perception of auditory signals from hearing aids or cochlear implants, is how oralism continues on in the current day.

Manualism is a method of education of deaf students using sign language within the classroom. Manualism arose in the late 18th century with the advent of free public schools for the deaf in Europe. These teaching methods were brought over to the United States where the first school for the deaf was established in 1817. Today manualism methods are used in conjunction with oralism methods in the majority of American deaf schools.

Louis Laurent Marie Clerc was a French teacher called "The Apostle of the Deaf in America" and was regarded as the most renowned deaf person in American Deaf History. He was taught by Abbé Sicard and deaf educator Jean Massieu, at the Institution Nationale des Sourds-Muets in Paris. With Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, he co-founded the first school for the deaf in North America, the Asylum for the Education and Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, on April 15, 1817, in the old Bennet's City Hotel, Hartford, Connecticut. The school was subsequently renamed the American School for the Deaf and in 1821 moved to 139 Main Street, West Hartford. The school remains the oldest existing school for the deaf in North America.

The British Deaf Association (BDA) is a deaf-led British charity that campaigns and advocates for deaf people who use British Sign Language.

The recorded history of sign language in Western societies starts in the 17th century, as a visual language or method of communication, although references to forms of communication using hand gestures date back as far as 5th century BC Greece. Sign language is composed of a system of conventional gestures, mimic, hand signs and finger spelling, plus the use of hand positions to represent the letters of the alphabet. Signs can also represent complete ideas or phrases, not only individual words.

Van Asch Deaf Education Centre was located in Truro Street, Sumner, Christchurch, New Zealand. It was a special school for deaf children, accepting both day and residential pupils, as well being as a resource centre providing services and support for parents, mainstream students and their teachers in the South Island and the Lower North Island.

The history of deaf people and deaf culture make up deaf history. The Deaf culture is a culture that is centered on sign language and relationships among one another. Unlike other cultures the Deaf culture is not associated with any native land as it is a global culture. By some, deafness may be viewed as a disability, but the Deaf world sees itself as a language minority. Throughout the years many accomplishments have been achieved by deaf people. To name the most famous, Ludwig van Beethoven and Thomas Alva Edison were both deaf and contributed great works to culture.

Italian Sign Language or LIS is the visual language used by deaf people in Italy. Deep analysis of it began in the 1980s, along the lines of William Stokoe's research on American Sign Language in the 1960s. Until the beginning of the 21st century, most studies of Italian Sign Language dealt with its phonology and vocabulary. According to the European Union for the Deaf, the majority of the 60,000–90,000 Deaf people in Italy use LIS.

In the United States, deaf culture was born in Connecticut in 1817 at the American School for the Deaf, when a deaf teacher from France, Laurent Clerc, was recruited by Thomas Gallaudet to help found the new institution. Under the guidance and instruction of Clerc in language and ways of living, deaf American students began to evolve their own strategies for communication and for living, which became the kernel for the development of American Deaf culture.

Deaf education is the education of students with any degree of hearing loss or deafness. This may involve, but does not always, individually-planned, systematically-monitored teaching methods, adaptive materials, accessible settings, and other interventions designed to help students achieve a higher level of self-sufficiency and success in the school and community than they would achieve with a typical classroom education. There are different language modalities used in educational setting where students get varied communication methods. A number of countries focus on training teachers to teach deaf students with a variety of approaches and have organizations to aid deaf students.

Francis Maginn (1861–1918) was a Church of Ireland missionary who worked to improve living standards for the deaf community by promoting sign language and was one of the co-founders of the British Deaf Association.

The history of deaf education in the United States began in the early 1800s when the Cobbs School of Virginia, an oral school, was established by William Bolling and John Braidwood, and the Connecticut Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, a manual school, was established by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc. When the Cobbs School closed in 1816, the manual method, which used American Sign Language, became commonplace in deaf schools for most of the remainder of the century. In the late 1800s, schools began to use the oral method, which only allowed the use of speech, as opposed to the manual method previously in place. Students caught using sign language in oral programs were often punished. The oral method was used for many years until sign language instruction gradually began to come back into deaf education.

The Deaf rights movement encompasses a series of social movements within the disability rights and cultural diversity movements that encourages deaf and hard of hearing to push society to adopt a position of equal respect for them. Acknowledging that those who were Deaf or hard of hearing had rights to obtain the same things as those hearing lead this movement. Establishing an educational system to teach those with Deafness was one of the first accomplishments of this movement. Sign language, as well as cochlear implants, has also had an extensive impact on the Deaf community. These have all been aspects that have paved the way for those with Deafness, which began with the Deaf Rights movement.

Harriet Burbank Rogers was an American educator, a pioneer in the oral method of instruction of the deaf. She was the first director of Clarke School for the Deaf, the first U.S. institution to teach the deaf by articulation and lip reading rather than by signing. Her advocacy for oralist instruction children increased utilization of oral-only communication models in many American schools.

The establishment of schools and institutions specializing in deaf education has a history spanning back across multiple centuries. They utilized a variety of instructional approaches and philosophies. The manner in which the language barrier is handled between the hearing and the deaf remains a topic of great controversy. Many of the early establishments of formalized education for the deaf are currently acknowledged for the influence they've contributed to the development and standards of deaf education today.