The South African Republic, also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result of the Second Boer War.

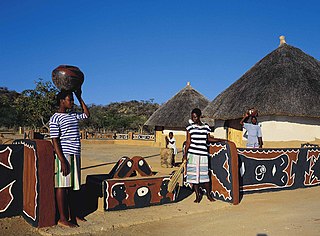

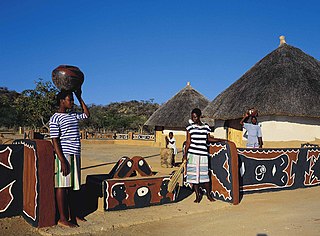

Artifacts indicating human activity dating back to the early Stone Age have been found in the Kingdom of Eswatini. The earliest known inhabitants of the region were Khoisan hunter-gatherers. Later, the population became predominantly Nguni during and after the great Bantu migrations. People speaking languages ancestral to the current Sotho and Nguni languages began settling no later than the 11th century. The country now derives its name from a later king named Mswati II. Mswati II was the greatest of the fighting kings of Eswatini, and he greatly extended the area of the country to twice its current size. The people of Eswatini largely belong to a number of clans that can be categorized as Emakhandzambili, Bemdzabu, and Emafikamuva, depending on when and how they settled in Eswatini.

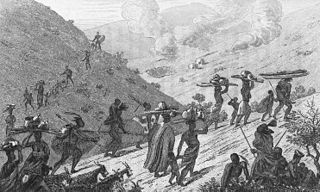

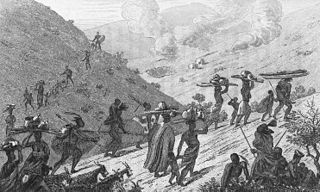

The Mfecane, also known by the Sesotho names Difaqane or Lifaqane is a historical period of heightened military conflict and migration associated with state formation and expansion in Southern Africa. The exact range of dates that comprise the Mfecane varies between sources. At its broadest the period lasted from the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century, but scholars often focus on an intensive period from the 1810s to the 1840s. The concept first emerged in the 1830s and blamed the disruption on the actions of Shaka Zulu, who was alleged to have waged near-genocidal wars that depopulated the land and sparked a chain reaction of violence as fleeing groups sought to conquer new lands. Since the later half of the 20th century, this interpretation has fallen out of favor among scholars due to a lack of historical evidence.

Andries Hendrik Potgieter, known as Hendrik Potgieter was a Voortrekker leader and the last known Champion of the Potgieter family. He served as the first head of state of Potchefstroom from 1840 and 1845 and also as the first head of state of Zoutpansberg from 1845 to 1852.

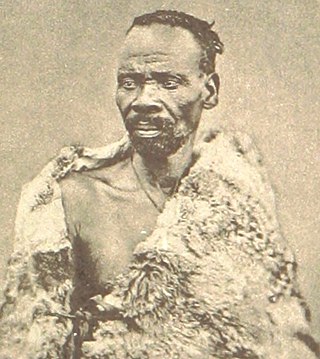

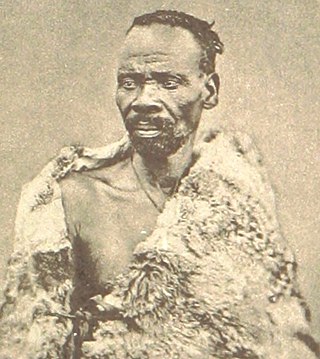

MzilikaziMoselekatse, Khumalo was a Southern African king who founded the Ndebele Kingdom now called Matebeleland which is now part of Zimbabwe. His name means "the great river of blood". He was born the son of Mashobane kaMangethe near Mkuze, Zululand, and died at Ingama, Matabeleland. Many consider him to be the greatest Southern African military leader after the Zulu king, Shaka. In his autobiography, David Livingstone referred to Mzilikazi as the second most impressive leader he encountered on the African continent.

The Northern Ndebele are a Mbo ethnic group native to South Africa who are an offshoot of the Southern Ndebele and they are concentrated in the Limpopo and North West provinces of South Africa.

South African Bantu-speaking peoples represent the overwhelming majority ethno-racial group of South Africans. Occasionally grouped as Bantu, the term itself is derived from the English word "people", common to many of the Bantu languages. The Oxford Dictionary of South African English describes "Bantu", when used in a contemporary usage and or racial context as "obsolescent and offensive", because of its strong association with the "white minority rule" with their apartheid system, however, Bantu is used without pejorative connotations in other parts of Africa and is still used in South Africa as the group term for the language family.

Mbandzeni (1855–1889) was the King of Swaziland from 1872 until 1889. Ingwenyama Mbandzeni was the son of Mswati II and Nandzi Nkambule. His mother the wife of King Mswati had died when he was still very young. Mbandzeni ascended to the throne after his half brother Ludvonga II died before he could become the king. Ludvonga's death resulted in his mother Inkhosikati Lamgangeni adopting Mbandzeni who was motherless as her son, thus making him king and her the queen mother of Swaziland. His royal capital was at Mbekelweni. During his kingship Mbandzeni granted many mining, farming, trading and administrative concessions to white settlers from Britain and the Transvaal. The Boers had tricked the king into signing permanent land concesions. The king could not read or write, so the Boers made him sign the concessions with a cross. The king was told that these were not permanent land concessions but the papers themselves stated otherwise. These concessions granted with the help of Offy Sherpstone eventually led to the conventions of 1884 and 1894, which reduced the overall borders of Swaziland and later made Swaziland a protectorate of the South African Republic. During a period of concessions preceded by famine around 1877 some of the tindvunas (governors) from within Swaziland like Mshiza Maseko and Ntengu kaGama Mbokane were given permission by King Mbandzeni to relocate to farms towards the Komati River and Lubombo regions, Mshiza Maseko later settled in a place called eLuvalweni towards Nkomati River, where he was later buried. Mbandzeni, still in command of a large Swazi army of more than 15,000 men aided the British in defeating Sekhukhune in 1879 and preventing Zulu incursion into the Transvaal during the same year. As a result, he guaranteed his country's independence and international recognition despite the Scramble for Africa which was taking place at the time. Mbandzeni died after an illness in 1889 and is quoted to have said in his deathbed "the Swazi kingship dies with me". He was buried at the royal cemetery at Mbilaneni alongside his father and grandfather Sobhuza I. Mbandzeni was succeeded by his young son Mahlokohla and his wife Queen Labotsibeni Mdluli after a 5 year regency of Queen Tibati Nkambule. Today a number of buildings and roads in Swaziland are named after Mbandzeni. Among these the Mbandzeni house in Mbabane and the Mbandzeni Highway to Siteki are named after him.

The military history of Zimbabwe chronicles a vast time period and complex events from the dawn of history until the present time. It covers invasions of native peoples of Africa, encroachment by Europeans, and civil conflict.

The Nguni people are a cultural group in southern Africa made of Bantu ethnic groups from South Africa, with off-shoots in neighbouring countries in Southern Africa. Swazi people live in both South Africa and Eswatini, while Northern Ndebele people live in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.

The Pedi or Bapedi, also known as Transvaal Sotho, Marota, or Bamaroteng, are a Sotho-Tswana people that speak Pedi or Sepedi which is one of the 12 official languages in South Africa. They are primarily situated in the Limpopo Province.

Sekhukhune I was the paramount King of the Marota, more commonly known as the Bapedi, from 21 September 1861 until his assassination on 13 August 1882 by his rival and half-brother, Mampuru II. As the Pedi paramount leader he was faced with political challenges from Voortrekkers, the independent South African Republic, the British Empire, and considerable social change caused by Christian missionaries.

AmaNdebele are an ethnic group native to South Africa who speak isiNdebele. They mainly inhabit the provinces of Mpumalanga, Gauteng and Limpopo, all of which are in the northeast of the country. In academia this ethnic group is referred to as the Southern Ndebele to differentiate it from their relatives maNdrebele who in turn are referred to as Northern Ndebele by academia.

Sekhukhuneland or Sekukuniland is a natural region in north-east South Africa, located in the historical Transvaal zone, former Transvaal Province, also known as Bopedi. The region is named after the 19th-century King, Sekhukhune I.

BAPO 2 is an ethnic rural village in the North West province of South Africa.

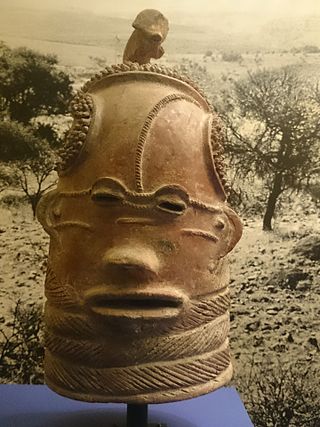

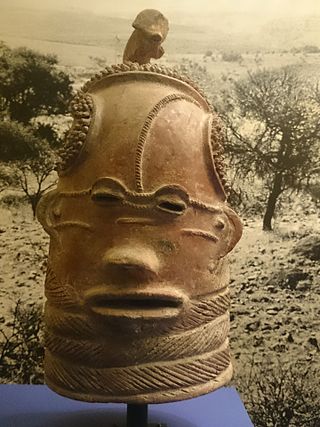

Bokoni was a pre-colonial, agro-pastoral society found in northwestern and southern parts of present-day Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Iconic to this area are stone-walled sites, found in a variety of shapes and forms. Bokoni sites also exhibit specialized farming and long-distance trading with other groups in surrounding regions. Bokoni saw occupation in varying forms between approximately 1500 and 1820 A.D.

Mampuru II was a king of the Pedi people in southern Africa. Mampuru was a son of the elder brother of Sekwati and claimed he had been designated as his successor.

Sekhukhune II was the paramount King of the Bapedi and grandson of Sekhukhune I. He reigned during the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Kgoshikgolo Thulare III, also known as King Victor Thulare III was the king of the Pedi people in South Africa. He was best known as being an economic freedom fighter for land and justice. He died on 6 January 2021, from COVID-19 complications during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. He was 40 years of age. King Thulare III's funeral was held on 17 January 2021 in Mohlaletsi, Limpopo, South Africa. He received a Special Official Category 1 funeral. The eulogy was delivered by President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa.

Nyabêla also known in Afrikaans as Niabel, was a chief of the Ndzundza-Ndebele during the nineteenth century. He is remembered for his struggle against whites for control of his tribe's own territory.