The history of the petroleum industry in the United States goes back to the early 19th century, although the indigenous peoples, like many ancient societies, have used petroleum seeps since prehistoric times; where found, these seeps signaled the growth of the industry from the earliest discoveries to the more recent.

Petroleum geology is the study of origin, occurrence, movement, accumulation, and exploration of hydrocarbon fuels. It refers to the specific set of geological disciplines that are applied to the search for hydrocarbons.

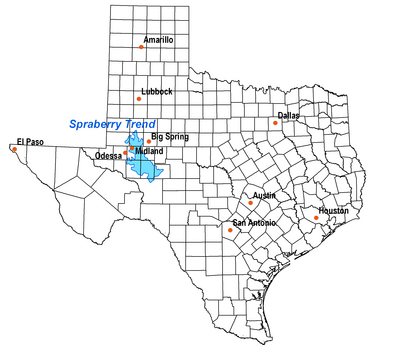

The Permian Basin is a large sedimentary basin in the southwestern part of the United States. The basin contains the Mid-continent oil field province. This sedimentary basin is located in western Texas and southeastern New Mexico. It reaches from just south of Lubbock, past Midland and Odessa, south nearly to the Rio Grande River in southern West Central Texas, and extending westward into the southeastern part of New Mexico. It is so named because it has one of the world's thickest deposits of rocks from the Permian geologic period. The greater Permian Basin comprises several component basins; of these, the Midland Basin is the largest, Delaware Basin is the second largest, and Marfa Basin is the smallest. The Permian Basin covers more than 86,000 square miles (220,000 km2), and extends across an area approximately 250 miles (400 km) wide and 300 miles (480 km) long.

North Sea oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons, comprising liquid petroleum and natural gas, produced from petroleum reservoirs beneath the North Sea.

The Tangguh gas field is a gas field lies in Berau Gulf and Bintuni Bay, in the province of West Papua, Indonesia. The natural gas field contains over 500 billion cubic metres of proven natural gas reserves, with estimates of potential reserves reaching over 800 billion cubic metres.

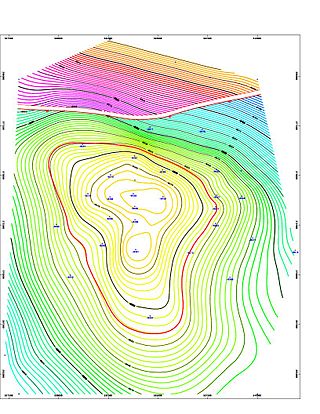

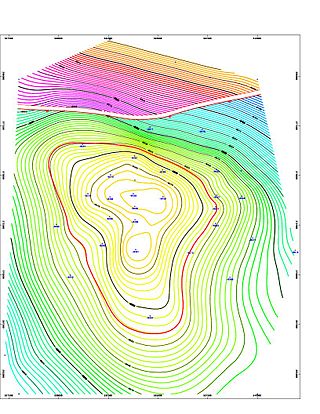

A petroleum reservoir or oil and gas reservoir is a subsurface accumulation of hydrocarbons contained in porous or fractured rock formations.

The East Texas Oil Field is a large oil and gas field in east Texas. Covering 140,000 acres (57,000 ha) and parts of five counties, and having 30,340 historic and active oil wells, it is the second-largest oil field in the United States outside Alaska, and first in total volume of oil recovered since its discovery in 1930. Over 5.42 billion barrels (862,000,000 m3) of oil have been produced from it to-date. It is a component of the Mid-continent oil province, the huge region of petroleum deposits extending from Kansas to New Mexico to the Gulf of Mexico.

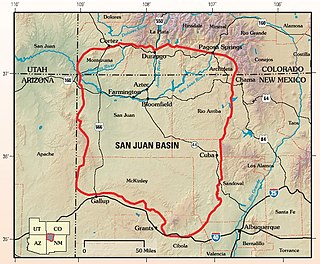

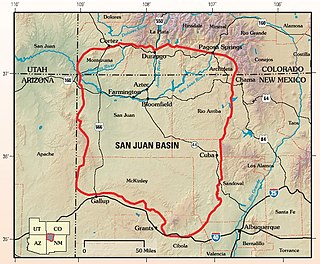

The San Juan Basin is a geologic structural basin located near the Four Corners region of the Southwestern United States. The basin covers 7,500 square miles and resides in northwestern New Mexico, southwestern Colorado, and parts of Utah and Arizona. Specifically, the basin occupies space in the San Juan, Rio Arriba, Sandoval, and McKinley counties in New Mexico, and La Plata and Archuleta counties in Colorado. The basin extends roughly 100 miles (160 km) N-S and 90 miles (140 km) E-W.

The Sirte Basin is a late Mesozoic and Cenozoic triple junction continental rift along northern Africa that was initiated during the late Jurassic Period. It borders a relatively stable Paleozoic craton and cratonic sag basins along its southern margins. The province extends offshore into the Mediterranean Sea, with the northern boundary drawn at the 2,000 meter (m) bathymetric contour. It borders in the north on the Gulf of Sidra and extends south into northern Chad.

The Sarir Field was discovered in southern Cyrenaica during 1961 and is considered to be the largest oil field in Libya, with estimated oil reserves of 12 Gbbl (1.9 km3). Sarir is operated by the Arabian Gulf Oil Company (AGOCO), a subsidiary of the state-owned National Oil Corporation (NOC).

The Bakken Formation is a rock unit from the Late Devonian to Early Mississippian age occupying about 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2) of the subsurface of the Williston Basin, underlying parts of Montana, North Dakota, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The formation was initially described by geologist J. W. Nordquist in 1953. The formation is entirely in the subsurface, and has no surface outcrop. It is named after Henry O. Bakken (1901–1982), a farmer in Tioga, North Dakota, who owned the land where the formation was initially discovered while drilling for oil.

The Bend Arch–Fort Worth Basin Province is a major petroleum producing geological system which is primarily located in North Central Texas and southwestern Oklahoma. It is officially designated by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) as Province 045 and classified as the Barnett-Paleozoic Total Petroleum System (TPS).

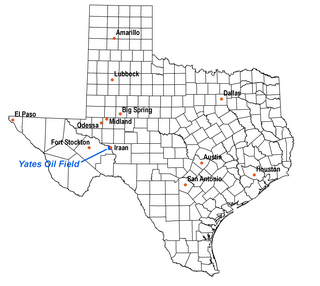

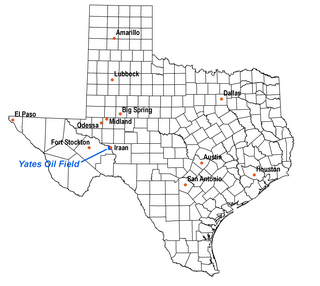

The Yates Oil Field is a giant oil field in the Permian Basin of west Texas. Primarily in extreme southeastern Pecos County, it also stretches under the Pecos River and partially into Crockett County. Iraan, on the Pecos River and directly adjacent to the field, is the nearest town. The field has produced more than one billion barrels of oil, making it one of the largest in the United States, and in 1998 it remains productive, though at a diminished rate. Since fracking has exploded in the Permian Basin, the Yates field has seen very heavy activity in the past three years. Estimated recoverable reserves are still approximately one billion barrels, which represents approximately 50% of the original oil in place (OOIP).

Tight oil is light crude oil contained in unconventional petroleum-bearing formations of low permeability, often shale or tight sandstone. Economic production from tight oil formations requires the same hydraulic fracturing and often uses the same horizontal well technology used in the production of shale gas. While sometimes called "shale oil", tight oil should not be confused with oil shale or shale oil. Therefore, the International Energy Agency recommends using the term "light tight oil" for oil produced from shales or other very low permeability formations, while the World Energy Resources 2013 report by the World Energy Council uses the terms "tight oil" and "shale-hosted oil".

The Cat Canyon Oil Field is a large oil field in the Solomon Hills of central Santa Barbara County, California, about 10 miles southeast of Santa Maria. It is the largest oil field in Santa Barbara County, and as of 2010 is the 20th-largest in California by cumulative production.

As of 2013 the Cline Shale, also referred to as the "Wolfcamp/Cline Shale", the "Lower Wolfcamp Shale", or the "Spraberry-Wolfcamp shale", or even the "Wolfberry", is a promising Pennsylvanian oil play east of Midland, Texas which underlies ten counties: Fisher, Nolan, Sterling, Coke, Glasscock, Tom Green, Howard, Mitchell, Borden and Scurry counties. Exploitation is projected to rely on hydraulic fracturing.

an organic rich shale, with Total Organic Content (TOC) of 1-8%, with silt and sand beds mixed in. It lies in a broad shelf, with minimal relief and has nice light oil of 38-42 gravity with excellent porosity of 6-12% in thickness varying 200 to 550 feet thick.

The Wattenberg Gas Field is a large producing area of natural gas and condensate in the Denver Basin of central Colorado, USA. Discovered in 1970, the field was one of the first places where massive hydraulic fracturing was performed routinely and successfully on thousands of wells. The field now covers more than 2,000 square miles between the cities of Denver and Greeley, and includes more than 23,000 wells producing from a number of Cretaceous formations. The bulk of the field is in Weld County, but it extends into Adams, Boulder, Broomfield, Denver, and Larimer Counties.

The Eagle Ford Group is a sedimentary rock formation deposited during the Cenomanian and Turonian ages of the Late Cretaceous over much of the modern-day state of Texas. The Eagle Ford is predominantly composed of organic matter-rich fossiliferous marine shales and marls with interbedded thin limestones. It derives its name from outcrops on the banks of the West Fork of the Trinity River near the old community of Eagle Ford, which is now a neighborhood within the city of Dallas. The Eagle Ford outcrop belt trends from the Oklahoma-Texas border southward to San Antonio, westward to the Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park, and the Quitman Mountains of West Texas. It also occurs in the subsurface of East Texas and South Texas, where it is the source rock for oil found in the Woodbine, Austin Chalk, and the Buda Limestone, and is produced unconventionally in South Texas and the "Eaglebine" play of East Texas. The Eagle Ford was one of the most actively drilled targets for unconventional oil and gas in the United States in 2010, but its output had dropped sharply by 2015. By the summer of 2016, Eagle Ford spending had dropped by two-thirds from $30 billion in 2014 to $10 billion, according to an analysis from the research firm Wood Mackenzie. This strike has been the hardest hit of any oil fields in the world. The spending was, however, expected to increase to $11.6 billion in 2017. A full recovery is not expected any time soon.

The West Siberian petroleum basin is the largest hydrocarbon basin in the world covering an area of about 2.2 million km², and is also the largest oil and gas producing region in Russia.

Carabobo is an oil field located in Venezuela's Orinoco Belt. As one of the world's largest accumulations of recoverable oil, the recent discoveries in the Orinoco Belt have led to Venezuela holding the world's largest recoverable reserves in the world, surpassing Saudi Arabia in July 2010. The Carabobo oil field is majority owned by Venezuela's national oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA). Owning the majority of the Orinoco Belt, and its estimated 1.18 trillion barrels of oil in place, PDVSA is now the fourth largest oil company in the world. The field is well known for its extra Heavy crude oils, having an average specific gravity between 4 and 16 °API. The Orinoco Belt holds 90% of the world's extra heavy crude oils, estimated at 256 billion recoverable barrels. While production is in its early development, the Carabobo field is expected to produce 400,000 barrels of oil per day.