DNA ligase is a specific type of enzyme, a ligase, that facilitates the joining of DNA strands together by catalyzing the formation of a phosphodiester bond. It plays a role in repairing single-strand breaks in duplex DNA in living organisms, but some forms may specifically repair double-strand breaks. Single-strand breaks are repaired by DNA ligase using the complementary strand of the double helix as a template, with DNA ligase creating the final phosphodiester bond to fully repair the DNA.

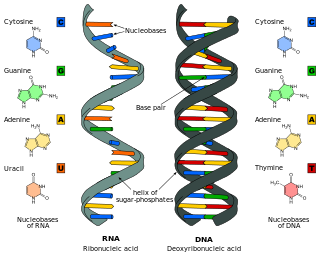

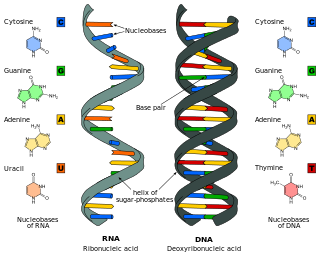

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic acids are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). If the sugar is ribose, the polymer is RNA; if the sugar is the ribose derivative deoxyribose, the polymer is DNA.

A primer is a short single-stranded nucleic acid used by all living organisms in the initiation of DNA synthesis. DNA polymerase enzymes are only capable of adding nucleotides to the 3’-end of an existing nucleic acid, requiring a primer be bound to the template before DNA polymerase can begin a complementary strand. DNA polymerase adds nucleotides after binding to the RNA primer and synthesizes the whole strand. Later, the RNA strands must be removed accurately and replace them with DNA nucleotides forming a gap region known as a nick that is filled in using an enzyme called ligase. The removal process of the RNA primer requires several enzymes, such as Fen1, Lig1, and others that work in coordination with DNA polymerase, to ensure the removal of the RNA nucleotides and the addition of DNA nucleotides. Living organisms use solely RNA primers, while laboratory techniques in biochemistry and molecular biology that require in vitro DNA synthesis usually use DNA primers, since they are more temperature stable. Primers can be designed in laboratory for specific reactions such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). When designing PCR primers, there are specific measures that must be taken into consideration, like the melting temperature of the primers and the annealing temperature of the reaction itself. Moreover, the DNA binding sequence of the primer in vitro has to be specifically chosen, which is done using a method called basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) that scans the DNA and finds specific and unique regions for the primer to bind.

Deoxyribose, or more precisely 2-deoxyribose, is a monosaccharide with idealized formula H−(C=O)−(CH2)−(CHOH)3−H. Its name indicates that it is a deoxy sugar, meaning that it is derived from the sugar ribose by loss of a hydroxy group. Deoxyribose is most notable for its presence in DNA. Since the pentose sugars arabinose and ribose only differ by the stereochemistry at C2′, 2-deoxyribose and 2-deoxyarabinose are equivalent, although the latter term is rarely used because ribose, not arabinose, is the precursor to deoxyribose.

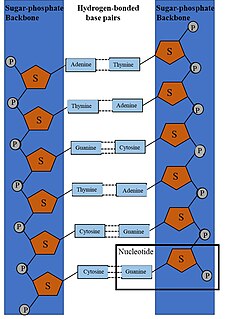

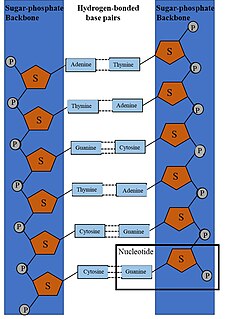

DNA synthesis is the natural or artificial creation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules. DNA is a macromolecule made up of nucleotide units, which are linked by covalent bonds and hydrogen bonds, in a repeating structure. DNA synthesis occurs when these nucleotide units are joined to form DNA; this can occur artificially or naturally. Nucleotide units are made up of a nitrogenous base, pentose sugar (deoxyribose) and phosphate group. Each unit is joined when a covalent bond forms between its phosphate group and the pentose sugar of the next nucleotide, forming a sugar-phosphate backbone. DNA is a complementary, double stranded structure as specific base pairing occurs naturally when hydrogen bonds form between the nucleotide bases.

A nuclease is an enzyme capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds between nucleotides of nucleic acids. Nucleases variously effect single and double stranded breaks in their target molecules. In living organisms, they are essential machinery for many aspects of DNA repair. Defects in certain nucleases can cause genetic instability or immunodeficiency. Nucleases are also extensively used in molecular cloning.

A cDNA library is a combination of cloned cDNA fragments inserted into a collection of host cells, which constitute some portion of the transcriptome of the organism and are stored as a "library". cDNA is produced from fully transcribed mRNA found in the nucleus and therefore contains only the expressed genes of an organism. Similarly, tissue-specific cDNA libraries can be produced. In eukaryotic cells the mature mRNA is already spliced, hence the cDNA produced lacks introns and can be readily expressed in a bacterial cell. While information in cDNA libraries is a powerful and useful tool since gene products are easily identified, the libraries lack information about enhancers, introns, and other regulatory elements found in a genomic DNA library.

Endonucleases are enzymes that cleave the phosphodiester bond within a polynucleotide chain. Some, such as deoxyribonuclease I, cut DNA relatively nonspecifically, while many, typically called restriction endonucleases or restriction enzymes, cleave only at very specific nucleotide sequences. Endonucleases differ from exonucleases, which cleave the ends of recognition sequences instead of the middle (endo) portion. Some enzymes known as "exo-endonucleases", however, are not limited to either nuclease function, displaying qualities that are both endo- and exo-like. Evidence suggests that endonuclease activity experiences a lag compared to exonuclease activity.

In biochemistry and molecular genetics, an AP site, also known as an abasic site, is a location in DNA that has neither a purine nor a pyrimidine base, either spontaneously or due to DNA damage. It has been estimated that under physiological conditions 10,000 apurinic sites and 500 apyrimidinic may be generated in a cell daily.

Restriction sites, or restriction recognition sites, are located on a DNA molecule containing specific sequences of nucleotides, which are recognized by restriction enzymes. These are generally palindromic sequences, and a particular restriction enzyme may cut the sequence between two nucleotides within its recognition site, or somewhere nearby.

A nick is a discontinuity in a double stranded DNA molecule where there is no phosphodiester bond between adjacent nucleotides of one strand typically through damage or enzyme action. Nicks allow DNA strands to untwist during replication, and are also thought to play a role in the DNA mismatch repair mechanisms that fix errors on both the leading and lagging daughter strands.

A restriction fragment is a DNA fragment resulting from the cutting of a DNA strand by a restriction enzyme, a process called restriction. Each restriction enzyme is highly specific, recognising a particular short DNA sequence, or restriction site, and cutting both DNA strands at specific points within this site. Most restriction sites are palindromic,, and are four to eight nucleotides long. Many cuts are made by one restriction enzyme because of the chance repetition of these sequences in a long DNA molecule, yielding a set of restriction fragments. A particular DNA molecule will always yield the same set of restriction fragments when exposed to the same restriction enzyme. Restriction fragments can be analyzed using techniques such as gel electrophoresis or used in recombinant DNA technology.

This glossary of genetics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts commonly used in the study of genetics and related disciplines in biology, including molecular biology, cell biology, and evolutionary biology. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical detail, see the article corresponding to each term. For related terms, see Glossary of evolutionary biology.

In cell biology, ways in which fragmentation is useful for a cell: DNA cloning and apoptosis. DNA cloning is important in asexual reproduction or creation of identical DNA molecules, and can be performed spontaneously by the cell or intentionally by laboratory researchers. Apoptosis is the programmed destruction of cells, and the DNA molecules within them, and is a highly regulated process. These two ways in which fragmentation is used in cellular processes describe normal cellular functions and common laboratory procedures performed with cells. However, problems within a cell can sometimes cause fragmentation that results in irregularities such as red blood cell fragmentation and sperm cell DNA fragmentation.

BglII is a type II restriction endonuclease isolated from certain strains of Bacillus globigii.

TOPO cloning is a molecular biology technique in which DNA fragments are cloned into specific vectors without the requirement for DNA ligases. Taq polymerase has a nontemplate-dependent terminal transferase activity that adds a single deoxyadenosine (A) to the 3'-end of the PCR products. This characteristic is exploited in "sticky end" TOPO TA cloning. For "blunt end" TOPO cloning, the recipient vector does not have overhangs and blunt-ended DNA fragments can be cloned.

Nucleic acid structure refers to the structure of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA. Chemically speaking, DNA and RNA are very similar. Nucleic acid structure is often divided into four different levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

In molecular biology, ligation is the joining of two nucleic acid fragments through the action of an enzyme. It is an essential laboratory procedure in the molecular cloning of DNA, whereby DNA fragments are joined to create recombinant DNA molecules (such as when a foreign DNA fragment is inserted into a plasmid). The ends of DNA fragments are joined by the formation of phosphodiester bonds between the 3'-hydroxyl of one DNA terminus with the 5'-phosphoryl of another. RNA may also be ligated similarly. A co-factor is generally involved in the reaction, and this is usually ATP or NAD+.

This glossary of genetics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts commonly used in the study of genetics and related disciplines in biology, including molecular biology, cell biology, and evolutionary biology. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical detail, see the article corresponding to each term. For related terms, see Glossary of evolutionary biology.

This glossary of genetics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts commonly used in the study of genetics and related disciplines in biology, including molecular biology, cell biology, and evolutionary biology. It is split across two articles: