Related Research Articles

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. It prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and sets requirements for issuing warrants: warrants must be issued by a judge or magistrate, justified by probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and must particularly describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.

Harris Corporation was an American technology company, defense contractor, and information technology services provider that produced wireless equipment, tactical radios, electronic systems, night vision equipment and both terrestrial and spaceborne antennas for use in the government, defense and commercial sectors. They specialized in surveillance solutions, microwave weaponry, and electronic warfare. In 2019, it merged with L3 Technologies to form L3Harris Technologies.

Mobile phone tracking is a process for identifying the location of a mobile phone, whether stationary or moving. Localization may be affected by a number of technologies, such as the multilateration of radio signals between (several) cell towers of the network and the phone or by simply using GNSS. To locate a mobile phone using multilateration of mobile radio signals, the phone must emit at least the idle signal to contact nearby antenna towers and does not require an active call. The Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) is based on the phone's signal strength to nearby antenna masts.

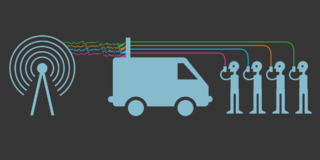

An international mobile subscriber identity-catcher, or IMSI-catcher, is a telephone eavesdropping device used for intercepting mobile phone traffic and tracking location data of mobile phone users. Essentially a "fake" mobile tower acting between the target mobile phone and the service provider's real towers, it is considered a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack. The 3G wireless standard offers some risk mitigation due to mutual authentication required from both the handset and the network. However, sophisticated attacks may be able to downgrade 3G and LTE to non-LTE network services which do not require mutual authentication.

The All Writs Act is a United States federal statute, codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1651, which authorizes the United States federal courts to "issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law."

Triggerfish describes a technology of cell phone interception and surveillance using a mobile cellular base station. The devices are also known as cell-site simulators or digital analyzers.

United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400 (2012), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the court held that installing a Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking device on a vehicle and using the device to monitor the vehicle's movements constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment.

The StingRay is an IMSI-catcher, a cellular phone surveillance device, manufactured by Harris Corporation. Initially developed for the military and intelligence community, the StingRay and similar Harris devices are in widespread use by local and state law enforcement agencies across Canada, the United States, and in the United Kingdom. Stingray has also become a generic name to describe these kinds of devices.

People v. Diaz, 51 Cal. 4th 84, 244 P.3d 501, 119 Cal. Rptr. 3d 105 was a Supreme Court of California case, which held that police are not required to obtain a warrant to search information contained within a cell phone in a lawful arrest. In a sting operation conducted by local police, the defendant, Gregory Diaz, was arrested for the sale of the illicit drug ecstasy and his cellphone, containing incriminating evidence, was seized and searched without a warrant. In trial court proceedings, Diaz motioned to suppress the information obtained from his cellphone, which was denied on the grounds that the search of his cellphone was incident to a lawful arrest. The California Court of Appeal affirmed the court's decision and was later upheld by the California Supreme Court. In 2014, the United States Supreme Court overruled that position in Riley v. California and held that without a warrant, police may not search the digital information on a cellphone that has been seized incident to arrest.

United States v. Graham, 846 F. Supp. 2d 384, was a Maryland District Court case in which the Court held that historical cell site location data is not protected by the Fourth Amendment. Reacting to the precedent established by the recent Supreme Court case United States v. Jones in conjunction with the application of the third party doctrine, Judge Richard D. Bennett, found that "information voluntarily disclosed to a third party ceases to enjoy Fourth Amendment protection" because that information no longer belongs to the consumer, but rather to the telecommunications company that handles the transmissions records. The historical cell site location data is then not subject to the privacy protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment standard of probable cause, but rather to the Stored Communications Act, which governs the voluntary or compelled disclosure of stored electronic communications records.

Glik v. Cunniffe, 655 F.3d 78 is a case in which the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit held that a private citizen has the right to record video and audio of police carrying out their duties in a public place, and that the arrest of the citizen for a wiretapping violation violated his First and Fourth Amendment rights. The case arose when Simon Glik filmed Boston, Massachusetts, police officers from the bicycle unit making an arrest in a public park. When the officers observed that Glik was recording the arrest, they arrested him and Glik was subsequently charged with wiretapping, disturbing the peace, and aiding in the escape of a prisoner. Glik then sued the City of Boston and the arresting officers, claiming that they violated his constitutional rights.

Cellphone surveillance may involve tracking, bugging, monitoring, eavesdropping, and recording conversations and text messages on mobile phones. It also encompasses the monitoring of people's movements, which can be tracked using mobile phone signals when phones are turned on.

Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373 (2014), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the court ruled that the warrantless search and seizure of the digital contents of a cell phone during an arrest is unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment.

A dirtbox is a cell site simulator, a phone device mimicking a cell phone tower, that creates a signal strong enough to cause nearby dormant mobile phones to switch to it. Mounted on aircraft, it is used by the United States Marshals Service to locate and collect information from cell phones believed to be connected with criminal activity. It can also be used to jam phones. The device's name comes from the company that developed it, Digital Receiver Technology, Inc. (DRT), owned by the Boeing company. Boeing describes the device as a hybrid of "jamming, managed access and detection". A similar device with a smaller range, the controversial StingRay phone tracker, has been widely used by U.S. federal entities, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

R v Fearon, 2014 SCC 77 is a leading section 8 Canadian constitutional law case, concerning the constitutionality of warrantless law enforcement searches of the contents of a cell phone incident to arrest.

The Apple–FBI encryption dispute concerns whether and to what extent courts in the United States can compel manufacturers to assist in unlocking cell phones whose data are cryptographically protected. There is much debate over public access to strong encryption.

Network Investigative Technique, or NIT, is a form of malware employed by the FBI since at least 2002. It is a drive-by download computer program designed to provide access to a computer.

Playpen was a notorious darknet child pornography website that operated from August 2014 to March 2015. The website operated through the Tor network which allowed users to use the website anonymously. After running the website for 6 months, the website owner Steven W. Chase was captured by the FBI. After his capture, the FBI continued to run the website for another 13 days as part of Operation Pacifier.

Carpenter v. United States, 585 U.S. ___, 138 S.Ct. 2206 (2018), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case concerning the privacy of historical cell site location information (CSLI). The Court held that the government violates the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution when it accesses historical CSLI records containing the physical locations of cellphones without a search warrant.

Fog Reveal is a tracking tool that aggregates location data from mobile apps. It is a product of FOG Data Science.

References

- ↑ Ryan Gallagher (15 Feb 2013). "FBI Files Unlock History Behind Clandestine Cellphone Tracking Tool". Slate. Retrieved 17 Aug 2016.

- 1 2 Justin Fenton (9 Apr 2015). "Baltimore Police used secret technology to track cellphones in thousands of cases". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- 1 2 3 JOSEPH GOLDSTEIN (11 Feb 2016). "New York Police Are Using Covert Cellphone Trackers, Civil Liberties Group Says". New York Times. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- 1 2 Justin Fenton (25 Apr 2016). "Key evidence in city murder case tossed due to stingray use". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Jessica Glenza, Nicky Woolf (10 Apr 2015). "Stingray spying: FBI's secret deal with police hides phone dragnet from courts". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Kim Zetter (4 Mar 2014). "Police Contract With Spy Tool Maker Prohibits Talking About Device's Use". Wired. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Ryan Gallagher (10 Jan 2013). "FBI Documents Shine Light on Clandestine Cellphone Tracking Tool". Slate. Retrieved 17 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Ellen Nakashima (27 Mar 2013). "Little-known surveillance tool raises concerns by judges, privacy activists". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Brad Heath (24 Aug 2015). "Police secretly track cellphones to solve routine crimes". USA Today. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Brian Barrett (16 Aug 2016). "The Baltimore PD's Race Bias Extends to High-Tech Spying, Too". Wired. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Kim Zetter (19 Jun 2014). "Emails Show Feds Asking Florida Cops to Deceive Judges". Wired. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Kim Zette (28 Oct 2015). "Turns Out Police Stingray Spy Tools Can Indeed Record Calls". Wired. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Richmond Sunlight » HB1408: Telecommunication records; warrant requirement, prohibition on collection by law enforcement". www.richmondsunlight.com. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- ↑ "CELL SITE SIMULATOR DEVICES--COLLECTION OF DATA--WARRANT" (PDF). 12 May 2015. Retrieved 7 Dec 2023.

- ↑ Cyrus Farivar (26 Apr 2016). "Judge rules in favor of "likely guilty" murder suspect found via stingray". Ars Technica. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Kim Zetter (3 Nov 2011). "Feds' Use of Fake Cell Tower: Did it Constitute a Search?". Wired. Retrieved 17 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Adrian Covert (23 Sep 2011). "The StingRay Is The Virtually Unknown Device the Government Uses to Track You Through Your Phone". Gizmodo. Retrieved 17 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Mike Masnick (27 Sep 2011). "Details Emerging On Stingray Technology, Allowing Feds To Locate People By Pretending To Be Cell Towers". Tech Dirt. Retrieved 17 Aug 2016.

- ↑ InstantJoseph (4 Nov 2011). "The Stingray: the cellphone tracker the government won't talk about". The Verge. Retrieved 17 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Jennifer Valentino-DeVries (22 Sep 2011). "'Stingray' Phone Tracker Fuels Constitutional Clash". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 17 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Cory Doctorow (14 Jan 2016). "How an obsessive jailhouse lawyer revealed the existence of stingray surveillance devices". BoingBoing. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Cale Guthrie Weissman (19 Jun 2015). "How an obsessive recluse blew the lid off the secret technology authorities use to spy on people's cellphones". Business Insider. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Appeals court: It doesn't matter how wanted man was found, even if via stingray". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ↑ "Appeals Court: No stingrays without a warrant, explanation to judge". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ↑ Alex Emmons (31 Mar 2016). "Maryland Appellate Court Rebukes Police for Concealing Use of Stingrays". The Intercept. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.

- ↑ Kim Zetter (6 Apr 2016). "Spy Tool Ruling Inches the Stingray Debate Closer to the Supreme Court". Wired. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Judge rules in favor of "likely guilty" murder suspect found via stingray". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ↑ "For the first time, federal judge tosses evidence obtained via stingray". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ↑ "FCC complaint: Baltimore Police breaking law with use of stingray phone trackers". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ↑ "Court: Locating suspect via stingray definitely requires a warrant". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ↑ "Another court tells police: Want to use a stingray? Get a warrant". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ↑ Jackman, Tom (2017-09-21). "Police use of 'StingRay' cellphone tracker requires search warrant, appeals court rules". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286 . Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ↑ "PRINCE JONES V. UNITED STATES" (PDF).

- ↑ "If NYPD cops want to snoop on your phone, they need a warrant, judge rules". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ↑ Farivar, Cyrus (2018-07-18). "Judge slams FBI for improper cellphone search, stingray use". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2019-02-15.

- ↑ Farivar, Cyrus (2018-09-08). ""Get a warrant"—Florida appeals court admonishes cops in two murder cases". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- 1 2 Nelson, E. Bradley (October 1, 2020). "Civil Tentative Rulings and Probate Pregrants For Matters Scheduled For Thursday, October 1, 2020" (PDF). Retrieved October 20, 2020.