An ethnic group or ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, society, culture, nation, religion, or social treatment within their residing area. Ethnicity is sometimes used interchangeably with the term nation, particularly in cases of ethnic nationalism, and is separate from the related concept of races.

Mestizo is a racial classification used to refer to a person of a combined European and Indigenous American ancestry. The term was used as an ethnic/racial category for mixed-race castas that evolved during the Spanish Empire. Although, broadly speaking, mestizo means someone of mixed European/Indigenous heritage, the term did not have a fixed meaning in the colonial period. It was a formal label for individuals in official documentation, such as censuses, parish registers, Inquisition trials, and other matters. Priests and royal officials might classify persons as mestizos, but individuals also used the term in self-identification.

The melting pot is a monocultural metaphor for a heterogeneous society becoming more homogeneous, the different elements "melting together" with a common culture; an alternative being a homogeneous society becoming more heterogeneous through the influx of foreign elements with different cultural backgrounds, possessing the potential to create disharmony within the previous culture. Historically, it is often used to describe the cultural integration of immigrants to the United States.

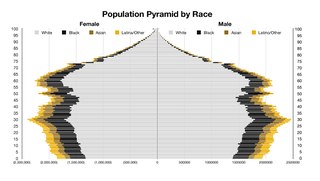

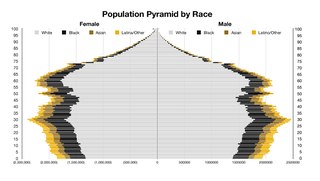

Race and ethnicity in the United States census, defined by the federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the United States Census Bureau, are the self-identified categories of race or races and ethnicity chosen by residents, with which they most closely identify, and indicate whether they are of Hispanic or Latino origin.

In the United States, the term hyphenated American refers to the use of a hyphen between the name of an ethnicity and the word "American" in compound nouns, e.g., as in "Irish-American". It was an epithet used from 1890 to 1920 to disparage Americans who were of foreign birth or origin, and who displayed an allegiance to a foreign country through the use of the hyphen. It was most commonly directed at German Americans or Irish Americans (Catholics) who called for U.S. neutrality in World War I.

European Americans are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent European arrivals. European Americans are the largest panethnic group in the United States, both historically and at present.

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone, and 71.0%, or 235,411,507 people, were white alone or combined with another race. Non-Latino whites totaled roughly 191,697,647, or 57.8%. White Latino Americans totaled about 12,579,626, or 3.8% of the population. European Americans are the largest panethnic group of white Americans and have constituted the majority population of the United States since the nation's founding.

The United States of America has a racially and ethnically diverse population. At the federal level, race and ethnicity have been categorized separately. The most recent United States Census officially recognized five racial categories as well as people of two or more races. The Census Bureau also classified respondents as "Hispanic or Latino" or "Not Hispanic or Latino", identifying Hispanic and Latino as an ethnicity, which comprises the largest minority group in the nation. The Census also asked an "Ancestry Question," which covers the broader notion of ethnicity, in the 2000 Census long form and the 2010 American Community Survey; the question worded differently on “origins” will return in the 2020 Census.

In sociology, racialization or ethnicization is a political process of ascribing ethnic or racial identities to a relationship, social practice, or group that did not identify itself as such. Racialization or ethnicization often arises out of the interaction of a group with a group that it dominates and ascribes a racial identity for the purpose of continued domination and social exclusion; over time, the racialized and ethnicized group develop the society enforced construct that races are real, different and unequal in ways that matter to economic, political and social life. These processes have been common throughout the history of imperialism, nationalism, racial and ethnic hierarchies.

Plastic Paddy is a slang expression for the cultural appropriation evidenced by unconvincing or obviously non-native Irishness. The phrase has been used as a positive reinforcement and as a derogatory term in various situations, particularly in London but also within Ireland itself. The term has sometimes been applied to people who may misappropriate or misrepresent stereotypical aspects of Irish customs. In this sense, the plastic Paddy may know little of actual Irish culture, but nevertheless assert an Irish identity. In other contexts, the term has been applied to members of the Irish diaspora who have distanced themselves from perceived stereotypes and, in the 1980s, the phrase was used to describe Irish people who had emigrated to England and were seeking assimilation into English culture.

In the United States, a white Hispanic or Latino is an individual who self-identifies as white and is of full or partial Hispanic or Latino descent, the largest group being white Mexican Americans. Although not differentiated in the U.S. Census definition, White Latino Americans may also be defined to include only those who identify as white and either originate from or have descent from countries in Latin America that speak Romance languages such as Brazil, Haiti, and French Guiana.

Panethnicity is a political neologism used to group various ethnic groups together based on their related cultural origins; geographic, linguistic, religious, or 'racial' similarities are often used alone or in combination to draw panethnic boundaries. The term panethnic was used extensively during mid-twentieth century anti-colonial/national liberation movements. In the United States, Yen Le Espiritu popularized the term and coined the nominal term panethnicity in reference to Asian Americans, a racial category composed of disparate peoples having in common only their origin in the continent of Asia.

Multiracial Americans are Americans who have mixed ancestry of two or more races. The term may also include Americans of mixed race ancestry who self-identify with just one group culturally and socially. In the 2010 US census, approximately 9 million individuals or 3.2% of the population, self-identified as multiracial. There is evidence that an accounting by genetic ancestry would produce a higher number. Historical reasons, including slavery creating a racial caste and the European-American suppression of Native Americans, often led people to identify or be classified by only one ethnicity, generally that of the culture in which they were raised. Prior to the mid-20th century, many people hid their multiracial heritage because of racial discrimination against minorities. While many Americans may be considered multiracial, they often do not know it or do not identify so culturally, any more than they maintain all the differing traditions of a variety of national ancestries.

American ancestry refers to people in the United States who self-identify their ancestral origin or descent as "American," rather than the more common officially recognized racial and ethnic groups that make up the bulk of the American people. The majority of these respondents are visibly White Americans, who either simply use this response as a political statement or are far removed from and no longer self-identify with their original ethnic ancestral origins. The latter response is attributed to a multitude of generational distance from ancestral lineages, and these tend be Anglo Americans, of English, Scotch-Irish, or other British ancestries, as demographers have observed that those ancestries tend to be recently undercounted in U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey ancestry self-reporting estimates. Although U.S. Census data indicates "American ancestry" is most commonly self-reported in the Deep South, the Upland South, and Appalachia, the vast majority of Americans and expatriates do not equate their nationality with ancestry, race, or ethnicity, but rather with citizenship and allegiance.

Hispanic and Latino are ethnonyms used to refer collectively to the inhabitants of the United States who are of Spanish or Latin American ancestry. While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, for example, by the United States Census Bureau, Hispanic includes people with ancestry from Spain and Latin American Spanish-speaking countries, while Latino includes people from Latin American countries that were formerly colonized by Spain and Portugal.

There is no single system of races or ethnicities that covers all modern Latin America, and usage of labels may vary substantially.

Mestizo Americans are Latino Americans whose racial and/or ethnic identity is Mestizo, i.e. a mixed ancestry of European and Amerindian from Latin America.

Transracial people identify as a different race than the one associated with their ancestry.

Matthew Windust Hughey is an American sociologist known for his work on race and racism. He is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Connecticut, where he is also an adjunct faculty member in the Africana Studies Institute and the American Studies Program. His work has included studying whiteness, race and media, race and politics, racism and racial assumptions within genetic and genomic science, and racism and racial identity in white and black American fraternities and sororities.

Yasuko I. Takezawa(竹沢泰子, born 1957) is a Japanese cultural anthropologist who researches race, ethnicity, and immigration in the United States, Japan, and other countries. She is a professor of cultural anthropology and sociology at the Institute for Research in the Humanities of Kyoto University.