Mulatto is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, but it does not have the same associations in languages such as Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. Among Latin Americans in the US, for instance, the term can be a source of pride. A mulatta is a female mulatto.

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron was a person with one-quarter African/Aboriginal and three-quarters European ancestry. Similar classifications were octoroon for one-eighth black and quintroon for one-sixteenth black.

"Children of the plantation" is a euphemism used to refer to people with ancestry tracing back to the time of slavery in the United States in which the offspring was born to black African female slaves in the context of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and Non-Black men, usually the slave's owner, one of the owner's relatives, or the plantation overseer. These children were often considered to be the property of the slave owner and were often subjected to the same treatment as other slaves on the plantation. Many of these children were born into slavery and had no legal rights, as they were not recognized as the legitimate children of their fathers. The men who fathered these children often used their power and authority to force themselves upon the black females who were under their control.

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also applied to people born free who were primarily of black African descent with little mixture. They were a distinct group of free people of color in the French colonies, including Louisiana and in settlements on Caribbean islands, such as Saint-Domingue (Haiti), St. Lucia, Dominica, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. In these territories and major cities, particularly New Orleans, and those cities held by the Spanish, a substantial third class of primarily mixed-race, free people developed. These colonial societies classified mixed-race people in a variety of ways, generally related to visible features and to the proportion of African ancestry. Racial classifications were numerous in Latin America.

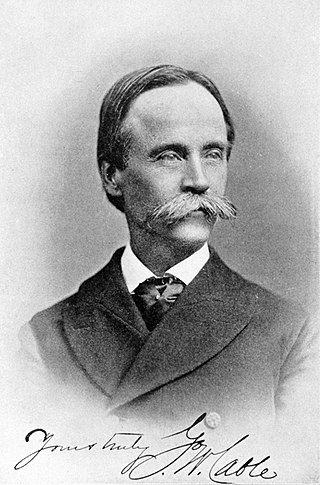

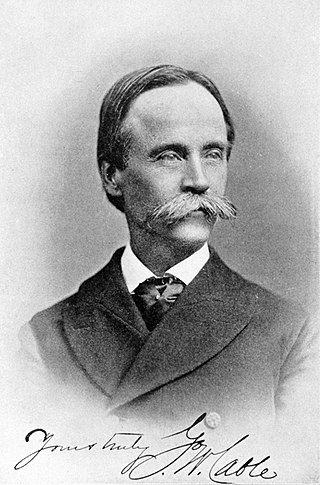

George Washington Cable was an American novelist notable for the realism of his portrayals of Creole life in his native New Orleans, Louisiana. He has been called "the most important southern artist working in the late 19th century", as well as "the first modern Southern writer." In his treatment of racism, mixed-race families and miscegenation, his fiction has been thought to anticipate that of William Faulkner.

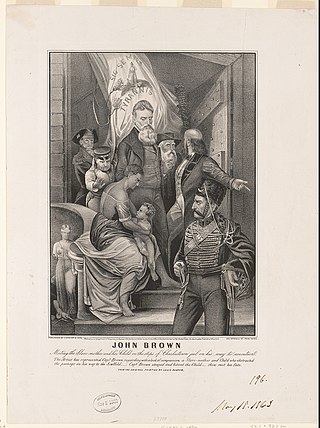

Clotel; or, The President's Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States is an 1853 novel by United States author and playwright William Wells Brown about Clotel and her sister, fictional slave daughters of Thomas Jefferson. Brown, who escaped from slavery in 1834 at the age of 20, published the book in London. He was staying after a lecture tour to evade possible recapture due to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Set in the early nineteenth century, it is considered the first novel published by an African American and is set in the United States. Three additional versions were published through 1867.

The tragic mulatto is a stereotypical fictional character that appeared in American literature during the 19th and 20th centuries, starting in 1837. The "tragic mulatto" is a stereotypical mixed-race person, who is assumed to be depressed, or even suicidal, because they fail to completely fit into the "white world" or the "black world". As such, the "tragic mulatto" is depicted as the victim of the society that is divided by race, where there is no place for one who is neither completely "black" nor "white".

Plaçage was a recognized extralegal system in French and Spanish slave colonies of North America by which ethnic European men entered into civil unions with non-Europeans of African, Native American and mixed-race descent. The term comes from the French placer meaning "to place with". The women were not legally recognized as wives but were known as placées; their relationships were recognized among the free people of color as mariages de la main gauche or left-handed marriages. They became institutionalized with contracts or negotiations that settled property on the woman and her children and, in some cases, gave them freedom if they were enslaved. The system flourished throughout the French and Spanish colonial periods, reaching its zenith during the latter, between 1769 and 1803.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of slave mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property; analogous legislation existed in other civilizations including Medieval Egypt in Africa and Korea in Asia.

Juan Victor Séjour Marcou et Ferrand was an American Creole of color and expatriate writer. Born in New Orleans, he spent most of his career in Paris. His fiction and plays were written and published in French. Although mostly unknown to later American writers of the nineteenth century, his short story "Le Mulâtre" is the earliest known work of fiction by an African American author. In France, however, he was known chiefly for his plays.

Louisiana Creoles are a Louisiana French ethnic group descended from the inhabitants of colonial Louisiana before it became a part of the United States during the period of both French and Spanish rule. They share cultural ties such as the traditional use of the French, Spanish, and Creole languages and predominant practice of Catholicism.

Sally Miller, born Salomé Müller, was an American woman enslaved sometime in the late 1810s, whose freedom suit in Louisiana was based on her claimed status as a free German immigrant and indentured servant born to non-enslaved parents. The case attracted wide attention and publicity because of the issue of "white" slavery. In Sally Miller v. Louis Belmonti, the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled in her favor, and Miller gained freedom.

Henriette Díaz DeLille, SSF was a Louisiana Creole of color and Catholic religious sister from New Orleans. She founded the Sisters of the Holy Family in 1836 and served as their first Mother Superior. The sisters are the second-oldest surviving congregation of African-American religious.

Atlantic Creole is a cultural identifier of those with origins in the transatlantic settlement of the Americas via Europe and Africa.

The Black elite is any elite, either political or economic in nature, that is made up of people who are of Black African descent. In the Western World, it is typically distinct from other national elites, such as the United Kingdom's aristocracy and the United States' upper class.

The Creoles of color are a historic ethnic group of Louisiana Creoles that developed in the former French and Spanish colonies of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Northwestern Florida, in what is now the United States. French colonists in Louisiana first used the term "Creole" to refer to people born in the colony, rather than in Europe, thus drawing a distinction between Old-World Europeans and Africans from their descendants born in the New World. Today, many of these Creoles of color have assimilated into Black culture, while some chose to remain a separate yet inclusive subsection of the African American ethnic group.

"Le Mulâtre" is a short story by Victor Séjour, a free person of color and Creole of color born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. It was written in French, Séjour's first language, and published in the Paris abolitionist journal Revue des Colonies in 1837. It is the earliest extant work of fiction by an African-American author. It was noted as such when it was first translated in English, appearing in the first edition of the Norton Anthology of African American Literature in 1997.

Bras-Coupé is the fictitious name of a slave named Squire, who lived from the early 19th century to 1837 in Louisiana.

Sapphira and the Slave Girl is Willa Cather's last novel, published in 1940. It is the story of Sapphira Dodderidge Colbert, a bitter white woman, who becomes irrationally jealous of Nancy, a beautiful young slave. The book balances an atmospheric portrait of antebellum Virginia against an unblinking view of the lives of Sapphira's slaves.

Afro-Haitians or Black Haitians are Haitians who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. They form the largest racial group in Haiti and together with other Afro-Caribbean groups, the largest racial group in the region.