The League of Nations was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. The main organization ceased operations on 20 April 1946 when many of its components were relocated into the new United Nations. As the template for modern global governance, the League profoundly shaped the modern world.

The Potsdam Conference was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They were represented respectively by General Secretary Joseph Stalin, Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee, and President Harry S. Truman. They gathered to decide how to administer Germany, which had agreed to an unconditional surrender nine weeks earlier. The goals of the conference also included establishing the postwar order, solving issues on the peace treaty, and countering the effects of the war.

The Munich Agreement was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Great Britain, the French Republic, and Fascist Italy. The agreement provided for the German annexation of part of Czechoslovakia called the Sudetenland, where more than three million people, mainly ethnic Germans, lived. The pact is also known in some areas as the Munich Betrayal, because of a previous 1924 alliance agreement and a 1925 military pact between France and the Czechoslovak Republic.

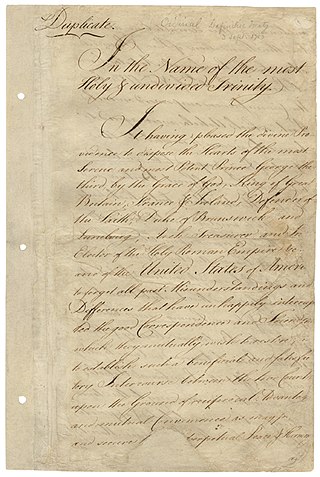

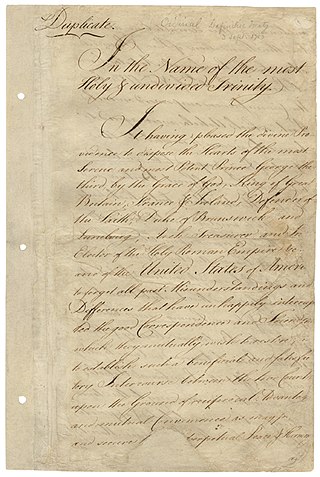

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of King George III of Great Britain and representatives of the United States on September 3, 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War and recognized the Thirteen Colonies, which had been part of colonial British America, as an independent, sovereign nation.

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress by President Woodrow Wilson. However, his main Allied colleagues were skeptical of the applicability of Wilsonian idealism.

The Treaty of Trianon often referred to as the PeaceDictate of Trianon or Dictate of Trianon in Hungary, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It formally ended World War I between most of the Allies of World War I and the Kingdom of Hungary. French diplomats played the major role in designing the treaty, with a view to establishing a French-led coalition of the newly formed states.

The Paris Peace Conference was a set of formal and informal diplomatic meetings in 1919 and 1920 after the end of World War I, in which the victorious Allies set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers. Dominated by the leaders of Britain, France, the United States and Italy, the conference resulted in five treaties that rearranged the maps of Europe and parts of Asia, Africa and the Pacific Islands, and also imposed financial penalties. Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and the other losing nations were not given a voice in the deliberations; this later gave rise to political resentments that lasted for decades. The arrangements made by this conference are considered one of the great watersheds of 20th-century geopolitical history.

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France.

Edgar Algernon Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood,, known as Lord Robert Cecil from 1868 to 1923, was a British lawyer, politician and diplomat. He was one of the architects of the League of Nations and a defender of it, whose service to the organisation saw him awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1937.

Alberta Hunter was an American jazz and blues singer and songwriter from the early 1920s to the late 1950s. After twenty years of working as a nurse, Hunter resumed her singing career in 1977.

The Supreme War Council was a central command based in Versailles that coordinated the military strategy of the principal Allies of World War I: Britain, France, Italy, the United States, and Japan. It was founded in 1917 after the Russian Revolution and with Russia's withdrawal as an ally imminent. The council served as a second source of advice for civilian leadership, a forum for preliminary discussions of potential armistice terms, later for peace treaty settlement conditions, and it was succeeded by the Conference of Ambassadors in 1920.

Warner Miller was an American businessman and politician from Herkimer, New York. A Republican, he was most notable for his service as a U.S. Representative (1879-1881) and United States Senator (1881-1887).

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Fairfax's Devisee v. Hunter's Lessee, 11 U.S. 603 (1813), was a United States Supreme Court case arising out of the acquisition of lands originally granted by the British King Charles II in 1649 to Lord Fairfax in the Northern Neck and westward.

The Big Four or the Four Nations refer to the four top Allied powers of World War I and their leaders who met at the Paris Peace Conference in January 1919. The Big Four is also known as the Council of Four. It was composed of Georges Clemenceau of France, David Lloyd George of the United Kingdom, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando of Italy, and Woodrow Wilson of the United States.

David Hunter Miller (1875–1961) was a US lawyer and an expert on treaties who participated in the drafting of the covenant of the League of Nations.

The Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on Enforcement of Penalties was a commission established at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Its role was to examine the background of the First World War, and to investigate and recommend individuals for prosecution for committing war crimes.

The Racial Equality Proposal was an amendment to the Treaty of Versailles that was considered at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Proposed by Japan, it was never intended to have any universal implications, but one was attached to it anyway, which caused its controversy. Japanese Foreign Minister Uchida Kōsai stated in June 1919 that the proposal was intended not to demand the racial equality of all coloured peoples but only that of members of the League of Nations.

Edward Frank Wise CB was a British economist, civil servant and Labour Party politician. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1929 to 1931.

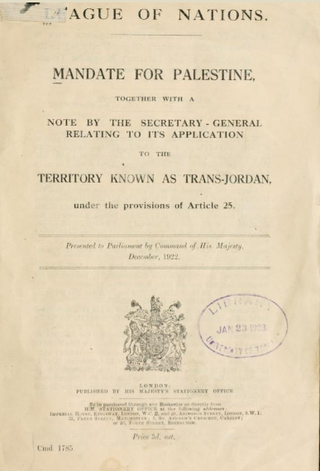

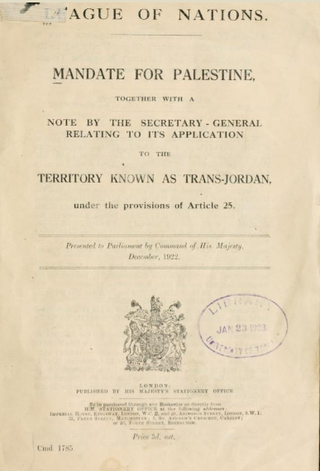

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The mandate was assigned to Britain by the San Remo conference in April 1920, after France's concession in the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement of the previously-agreed "international administration" of Palestine under the Sykes–Picot Agreement. Transjordan was added to the mandate after the Arab Kingdom in Damascus was toppled by the French in the Franco-Syrian War. Civil administration began in Palestine and Transjordan in July 1920 and April 1921, respectively, and the mandate was in force from 29 September 1923 to 15 May 1948 and to 25 May 1946 respectively.