Gian LorenzoBernini was an Italian sculptor and architect. While a major figure in the world of architecture, he was more prominently the leading sculptor of his age, credited with creating the Baroque style of sculpture. As one scholar has commented, "What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful ..." In addition, he was a painter and a man of the theatre: he wrote, directed and acted in plays, for which he designed stage sets and theatrical machinery. He produced designs as well for a wide variety of decorative art objects including lamps, tables, mirrors, and even coaches.

The Galleria Borghese is an art gallery in Rome, Italy, housed in the former Villa Borghese Pinciana. At the outset, the gallery building was integrated with its gardens, but nowadays the Villa Borghese gardens are considered a separate tourist attraction. The Galleria Borghese houses a substantial part of the Borghese Collection of paintings, sculpture and antiquities, begun by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the nephew of Pope Paul V. The building was constructed by the architect Flaminio Ponzio, developing sketches by Scipione Borghese himself, who used it as a villa suburbana, a country villa at the edge of Rome.

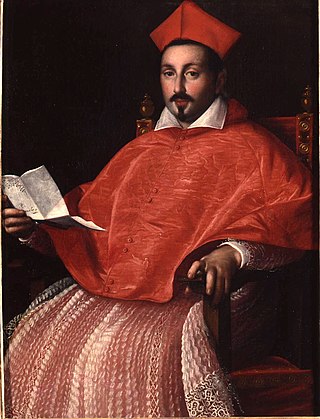

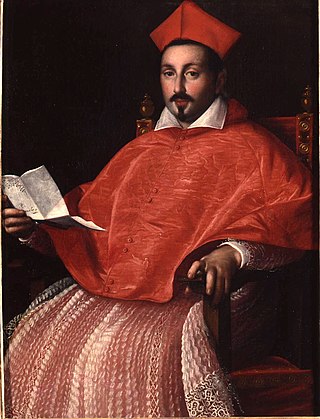

Scipione Borghese was an Italian cardinal, art collector and patron of the arts. A member of the Borghese family, he was the patron of the painter Caravaggio and the artist Bernini. His legacy is the establishment of the art collection at the Villa Borghese in Rome.

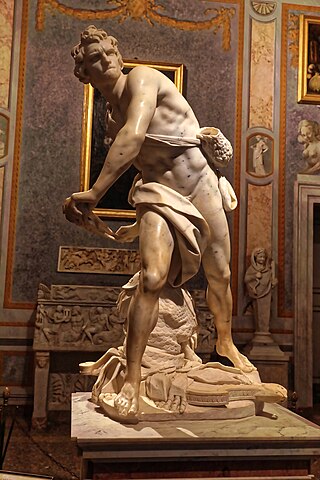

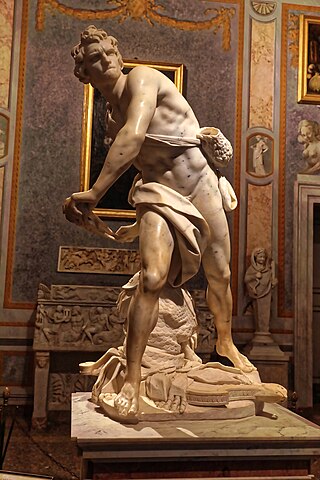

David is a life-size marble sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The sculpture was one of many commissions to decorate the villa of Bernini's patron Cardinal Scipione Borghese – where it still resides today, as part of the Galleria Borghese. It was completed in the course of eight months from 1623 to 1624.

Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius is a sculpture by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini created c. 1618–19. Housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, the sculpture depicts a scene from the Aeneid, where the hero Aeneas leads his family from burning Troy.

Fontana del Moro is a fountain located at the southern end of the Piazza Navona in Rome, Italy. It depicts a nautical scene with tritons, dolphins, and a conch shell. It was originally designed by Giacomo della Porta in the 1570s with later contributions from Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the 1650s. Bernini sculpted a large terracotta model of the central figure, which Giovanni Antonio Mari used as a guide when sculpting the final figure. There is a debate around whether or not the central figure was intended by Bernini to depict a Moor. Some of the original sculptures were moved to the Galleria Borghese in 1874. In 2011, the fountain was vandalized.

Apollo and Daphne is a life-sized marble sculpture by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini, which was executed between 1622 and 1625. It is regarded as one of the artistic marvels of the Baroque age. The statue is housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, along with several other examples of the artist's most important early works. The sculpture depicts the climax of the story of Apollo and Daphne, as written in Ovid's Metamorphoses, wherein the nymph Daphne escapes Apollo's advances by transforming into a laurel tree.

The Borghese Collection is a collection of Roman sculptures, old masters and modern art collected by the Roman Borghese family, especially Cardinal Scipione Borghese, from the 17th century on. It includes major collections of Caravaggio, Raphael, and Titian, and of ancient Roman art. Cardinal Scipione Borghese also bought widely from leading painters and sculptors of his time, and Scipione Borghese's commissions include two portrait busts by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Most of the collection remains intact and on display at the Galleria Borghese, although a significant sale of classical sculpture was made under duress to the Louvre in 1807.

The Sleeping Hermaphrodite is an ancient marble sculpture depicting Hermaphroditus life size. In 1620, Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini sculpted the mattress upon which the statue now lies. The form is partly derived from ancient portrayals of Venus and other female nudes, and partly from contemporaneous feminised Hellenistic portrayals of Dionysus/Bacchus. It represents a subject that was much repeated in Hellenistic times and in ancient Rome, to judge from the number of versions that have survived. Discovered at Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, the Sleeping Hermaphrodite was immediately claimed by Cardinal Scipione Borghese and became part of the Borghese Collection. The "Borghese Hermaphrodite" was later sold to the occupying French and was moved to The Louvre, where it is on display.

Blessed Ludovica Albertoni is a funerary monument by the Italian Baroque artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The Trastevere sculpture is located in the specially designed Altieri Chapel in the Church of San Francesco a Ripa in Rome, Italy. Bernini started the project in 1671, but his work on two other major works—The Tomb of Pope Alexander VII and the Altar of the Blessed Sacrament in St. Peter's Basilica—delayed his work on the funerary monument. Bernini completed the sculpture in 1674; it was installed by 31 August 1674.

Truth Unveiled by Time is a marble sculpture by Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini, one of the foremost sculptors of the Italian Baroque. Executed between 1645 and 1652, Bernini intended to show Truth allegorically as a naked young woman being unveiled by a figure of Time above her, but the figure of Time was never executed.

The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence is an early sculpture by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini. It shows the saint at the moment of his martyrdom, being burnt alive on a gridiron. According to Bernini's biographer, Filippo Baldinucci, the sculpture was completed when Bernini was 15 years old, implying that it was finished in the year 1614. Other historians have dated the sculpture between 1615 and 1618. A date of 1617 seems most likely. It is less than life-size in dimensions, measuring 108 by 66 cm.

The Bust of Louis XIV is a marble portrait by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini. It was created in the year 1665 during Bernini's visit to Paris. This sculptural portrait of Louis XIV of France has been called the "grandest piece of portraiture of the Baroque age". The bust is on display at the Versailles Palace, in the Salon de Diane in the King's Grand Apartment.

Two Busts of Cardinal Scipione Borghese are marble portrait sculptures executed by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini in 1632. Cardinal Scipione Borghese was the nephew of Pope Paul V, and had commissioned other works from Bernini in the 1620s. Both versions of this portrait are in the Galleria Borghese, Rome.

The Bust of Giovanni Battisti Santoni is a sculptural portrait by the Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Believed to be one of the artist's earliest works, the bust forms part of a tomb for Santoni, who was majordomo to Pope Sixtus V from 1590 to 1592. The work was executed sometime between 1613 and 1616, although some have dated the work as early as 1609, including Filippo Baldinucci. The work remains in its original setting in the church of Santa Prassede in Rome.

The Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini made two Busts of Pope Paul V. The first is currently in the Galleria Borghese in Rome. 1618 is the commonly accepted date for the portrait of the pope. In 2015, a second bust was acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. It was created by Bernini 1621, shortly after the death of Paul V, and commissioned by his nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese. A bronze version of this sculpture exists in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Saints Jerome and Mary Magdalen are two sculptures by the Italian artist Gianlorenzo Bernini. They sit in the Chigi Chapel of Siena Cathedral. The statues were commissioned as part of the chapel by the then–pope Alexander VII.

The Busts of Pope Innocent X are two portrait busts by the Italian artist Gianlorenzo Bernini of Pope Innocent X, Giovanni Battista Pamphili. Created around 1650, both sculptures are now in the Galleria Doria Pamphili in Rome. Like the two busts of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, it is believed that Bernini created a second version of the bust once a flaw was discovered in the first version. There exist several similar versions of the bust done by other artists, most notably Alessandro Algardi.

Habakkuk and the Angel is a sculpture created by Gian Lorenzo Bernini c. 1656–61. Standing in a niche in the Chigi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, it shows the Prophet Habakkuk with the angel of God. It forms a part of a larger composition with the sculpture of Daniel and the Lion diagonally opposite.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman is a large and complex marble statue by the Flemish sculptor and architect Giambologna. It was completed between 1579 and 1583 for Cosimo I de' Medici. Giambologna achieved widespread fame in his lifetime, and this work is widely considered his masterpiece. It has been in the Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, since August 1582.