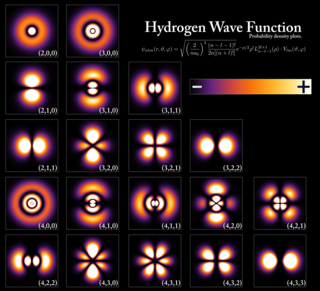

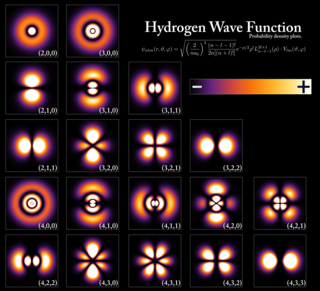

In quantum mechanics, an atomic orbital is a function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in an atom. This function describes the electron's charge distribution around the atom's nucleus, and can be used to calculate the probability of finding an electron in a specific region around the nucleus.

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli exclusion principle states that two or more identical particles with half-integer spins cannot simultaneously occupy the same quantum state within a system that obeys the laws of quantum mechanics. This principle was formulated by Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli in 1925 for electrons, and later extended to all fermions with his spin–statistics theorem of 1940.

The quantum Hall effect is a quantized version of the Hall effect which is observed in two-dimensional electron systems subjected to low temperatures and strong magnetic fields, in which the Hall resistance Rxy exhibits steps that take on the quantized values

Capacitance is the capability of a material object or device to store electric charge. It is measured by the charge in response to a difference in electric potential, expressed as the ratio of those quantities. Commonly recognized are two closely related notions of capacitance: self capacitance and mutual capacitance. An object that can be electrically charged exhibits self capacitance, for which the electric potential is measured between the object and ground. Mutual capacitance is measured between two components, and is particularly important in the operation of the capacitor, an elementary linear electronic component designed to add capacitance to an electric circuit.

Packing problems are a class of optimization problems in mathematics that involve attempting to pack objects together into containers. The goal is to either pack a single container as densely as possible or pack all objects using as few containers as possible. Many of these problems can be related to real-life packaging, storage and transportation issues. Each packing problem has a dual covering problem, which asks how many of the same objects are required to completely cover every region of the container, where objects are allowed to overlap.

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies slow-moving or stationary electric charges.

In computational physics and chemistry, the Hartree–Fock (HF) method is a method of approximation for the determination of the wave function and the energy of a quantum many-body system in a stationary state.

In atomic physics, the effective nuclear charge is the actual amount of positive (nuclear) charge experienced by an electron in a multi-electron atom. The term "effective" is used because the shielding effect of negatively charged electrons prevent higher energy electrons from experiencing the full nuclear charge of the nucleus due to the repelling effect of inner layer. The effective nuclear charge experienced by an electron is also called the core charge. It is possible to determine the strength of the nuclear charge by the oxidation number of the atom. Most of the physical and chemical properties of the elements can be explained on the basis of electronic configuration. Consider the behavior of ionization energies in the periodic table. It is known that the magnitude of ionization potential depends upon the following factors:

- Size of atom;

- The nuclear charge;

- The screening effect of the inner shells, and

- The extent to which the outermost electron penetrates into the charge cloud set up by the inner lying electron.

In statistical mechanics, the Potts model, a generalization of the Ising model, is a model of interacting spins on a crystalline lattice. By studying the Potts model, one may gain insight into the behaviour of ferromagnets and certain other phenomena of solid-state physics. The strength of the Potts model is not so much that it models these physical systems well; it is rather that the one-dimensional case is exactly solvable, and that it has a rich mathematical formulation that has been studied extensively.

The classical electron radius is a combination of fundamental physical quantities that define a length scale for problems involving an electron interacting with electromagnetic radiation. It links the classical electrostatic self-interaction energy of a homogeneous charge distribution to the electron's relativistic mass-energy. According to modern understanding, the electron is a point particle with a point charge and no spatial extent. Nevertheless, it is useful to define a length that characterizes electron interactions in atomic-scale problems. The classical electron radius is given as

Jellium, also known as the uniform electron gas (UEG) or homogeneous electron gas (HEG), is a quantum mechanical model of interacting electrons in a solid where the positive charges are assumed to be uniformly distributed in space; the electron density is a uniform quantity as well in space. This model allows one to focus on the effects in solids that occur due to the quantum nature of electrons and their mutual repulsive interactions without explicit introduction of the atomic lattice and structure making up a real material. Jellium is often used in solid-state physics as a simple model of delocalized electrons in a metal, where it can qualitatively reproduce features of real metals such as screening, plasmons, Wigner crystallization and Friedel oscillations.

The Madelung constant is used in determining the electrostatic potential of a single ion in a crystal by approximating the ions by point charges. It is named after Erwin Madelung, a German physicist.

The Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory, named after its originators, the physicists, Richard Feynman, and John Archibald Wheeler, is a theory of electrodynamics based on a relativistic correct extension of action at a distance electron particles. The theory postulates no independent electromagnetic field. Rather, the whole theory is encapsulated by the Lorentz-invariant action of particle trajectories defined as

In theoretical chemistry, Marcus theory is a theory originally developed by Rudolph A. Marcus, starting in 1956, to explain the rates of electron transfer reactions – the rate at which an electron can move or jump from one chemical species (called the electron donor) to another (called the electron acceptor). It was originally formulated to address outer sphere electron transfer reactions, in which the two chemical species only change in their charge with an electron jumping (e.g. the oxidation of an ion like Fe2+/Fe3+), but do not undergo large structural changes. It was extended to include inner sphere electron transfer contributions, in which a change of distances or geometry in the solvation or coordination shells of the two chemical species is taken into account (the Fe-O distances in Fe(H2O)2+ and Fe(H2O)3+ are different).

In statistical mechanics, the two-dimensional square lattice Ising model is a simple lattice model of interacting magnetic spins. The model is notable for having nontrivial interactions, yet having an analytical solution. The model was solved by Lars Onsager for the special case that the external magnetic field H = 0. An analytical solution for the general case for has yet to be found.

Implicit solvation is a method to represent solvent as a continuous medium instead of individual “explicit” solvent molecules, most often used in molecular dynamics simulations and in other applications of molecular mechanics. The method is often applied to estimate free energy of solute-solvent interactions in structural and chemical processes, such as folding or conformational transitions of proteins, DNA, RNA, and polysaccharides, association of biological macromolecules with ligands, or transport of drugs across biological membranes.

In solid-state physics, the t-J model is a model first derived by Józef Spałek to explain antiferromagnetic properties of Mott insulators, taking into account experimental results about the strength of electron-electron repulsion in this materials.

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron in 1932, models for a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons were quickly developed by Dmitri Ivanenko and Werner Heisenberg. An atom is composed of a positively charged nucleus, with a cloud of negatively charged electrons surrounding it, bound together by electrostatic force. Almost all of the mass of an atom is located in the nucleus, with a very small contribution from the electron cloud. Protons and neutrons are bound together to form a nucleus by the nuclear force.

In quantum mechanics, orbital magnetization, Morb, refers to the magnetization induced by orbital motion of charged particles, usually electrons in solids. The term "orbital" distinguishes it from the contribution of spin degrees of freedom, Mspin, to the total magnetization. A nonzero orbital magnetization requires broken time-reversal symmetry, which can occur spontaneously in ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials, or can be induced in a non-magnetic material by an applied magnetic field.

The linearized augmented-plane-wave method (LAPW) is an implementation of Kohn-Sham density functional theory (DFT) adapted to periodic materials. It typically goes along with the treatment of both valence and core electrons on the same footing in the context of DFT and the treatment of the full potential and charge density without any shape approximation. This is often referred to as the all-electron full-potential linearized augmented-plane-wave method (FLAPW). It does not rely on the pseudopotential approximation and employs a systematically extendable basis set. These features make it one of the most precise implementations of DFT, applicable to all crystalline materials, regardless of their chemical composition. It can be used as a reference for evaluating other approaches.