The Tucson artifacts, sometimes called the Tucson Lead Crosses, Tucson Crosses, Silverbell Road artifacts, or Silverbell artifacts, were thirty-one lead objects that Charles E. Manier and his family found in 1924 near Picture Rocks, Arizona, that were initially thought by some to be created by early Mediterranean civilizations that had crossed the Atlantic in the first century, but were later determined to be a hoax. [1] [2]

The find consisted of thirty-one lead objects, including crosses, swords, and religious/ceremonial paraphernalia, most of which bore Hebrew or Latin engraved inscriptions, pictures of temples, leaders' portraits, angels, and a dinosaur (inscribed on the lead blade of a sword). One contained the phrase "Calalus, the unknown land", which was used by believers as the name of the settlement. The objects also have Roman numerals ranging from 790 to 900 inscribed on them, which were sometimes interpreted to represent the date of their creation. The site contains no other artifacts, no pottery sherds, no broken glass, no human or animal remains, and no sign of hearths or housing. [3] [1]

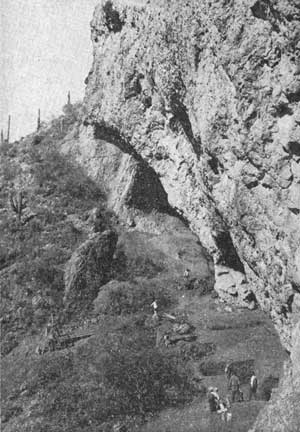

On September 13, 1924, Charles Manier and his father stopped to examine some old lime kilns while driving northwest of Tucson on Silverbell Road. Manier saw an object protruding about 2 inches (5.1 cm) from the soil. He dug it out, revealing that it was a lead cross measuring 20 inches (51 cm) and weighing 64 pounds (29 kg). Between 1924 and 1930 additional objects were extracted from the caliche, a layer of soil in which the soil particles have been cemented together by lime. [4] [5] Caliche often takes a long period of time to form, but it can be made and placed around an article in a short period of time, according to a report written by James Quinlan, a retired Tucson geologist who had worked for the U.S. Geological Survey. [1] [6] Quinlan also concluded that it would be easy to bury articles in the soft, silt material, and associated caliche in the lime kiln where the objects were found at the margin of prior trenches. [1] The objects were believed, by their discoverer and main supporters, to be of a Roman Judeo-Christian colony existing in what is now known as Arizona between 790 and 900 AD. No other find has been formally established as placing any Roman colony in the area, nor anywhere else in North America. [3]

In November 1924, Manier brought his friend Thomas Bent to the site and Bent was quickly convinced of the authenticity of the discovery. Upon finding the land was not owned, he immediately set up residence there, in order to homestead the property. Bent felt there was money to be made in further excavating the site. [3]

The first object removed from the caliche by Manier was a crudely cast metal cross that weighed 62 pounds (28 kg); after cleaning it was revealed to be two separate crosses riveted together. After his find, Manier took the cross to Professor Frank H. Fowler, Head of the Department of Classical Languages of the University of Arizona, at Tucson, who determined the language on the artifacts was Latin. He also translated one line as reading "Calalus, the unknown land", giving a name for the supposed Latin colony. [1]

The Latin inscriptions on the alleged artifacts supposedly record the conflicts of the leaders of Calalus against a barbarian enemy known as the "Toltezus", which some have interpreted as a supposed reference to the Mesoamerican Toltec civilization. [1] However, the Latin on the artifacts appears to either be badly inflected original Latin, or inscriptions brazenly plagiarized from Classical authors such as Virgil, Cicero, Livy, Cornelius Nepos, and Horace, among several others. This has led many experts to condemn the artifacts as frauds. [1] What is perhaps most suspicious, however, is that most of the inscriptions are identical to what appeared in widely available Latin grammar books, like Harkness's Latin Grammar and Allen and Greenough's Latin Grammar, as well as dictionaries like The Standard Dictionary of Facts. [1]

Manier took the first item to the Arizona State Museum to be studied by archaeologist Karl Ruppert. Ruppert was impressed with the item, and went with Manier to the site the next day where he found a caliche plaque weighing 7 pounds (3.2 kg), with inscriptions that included a date of 800 A.D. A total of thirty-one objects were found. [3] Other contemporary scholars including George C. Valliant, a Harvard University archaeologist who visited the University of Arizona in 1928, and Bashford Dean, curator of arms and armor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, thought the articles were fakes. [1] Neil Merton Judd, curator of the National Museum at the Smithsonian Institution, happened to be in Tucson at the time of the discovery of the objects and, after examining them, also thought they were fakes, proposing that they may have been created by "some mentally incompetent individual with a flair for old Latin and the wars of antiquity." [1] [7]

In the 1960s, Bent wrote a 350-page manuscript entitled "The Tucson Artifacts," about the objects, which is unpublished but kept by the Arizona State Museum. [3] Both Manier and Bent were supporters of the objects as a genuine archaeological find. [3]

Lara Coleman Ostrander, a Tucson immigrant and high school history teacher studied the historical background of the research, and translated the alleged history of Calalus from the writings on the items. Geologist Clifton J. Sarle worked with Ostrander to present the Tucson Artifacts to the press and the academic profession.

Tucson University administrator and director of the Arizona State Museum Dean Byron Cummings led archaeologists at the university to the location where the items were found. He brought ten of the objects to the American Association for the Advancement of Science and showing them at museums and universities on the east coast. Astronomer Andrew E. Douglass, known for his work in dendrochronology also considered the items to be authentic. [3]

In 1975, Wake Forest University professor Cyclone Covey re-examined the controversy in his book titled Calalus: A Roman Jewish Colony in America from the Time of Charlemagne Through Alfred the Great. Covey was in direct contact with Thomas Bent by 1970, and planned to carry out excavations at the site in 1972, but was not allowed, due to legal complications preventing Wake Forest University from leading a dig at the site. [3] Covey's book proposes that the objects are from a Jewish settlement, founded by people who came from Rome and settled outside of present-day Tucson around 800 AD. [5]

Professor Frank Fowler originally translated the Latin inscriptions on the first items and found that the inscriptions were from well known classical authors such as Cicero, Virgil and Horace. He researched local Latin texts available in Tucson at the time and found the inscriptions on the lead items to be identical to the texts available.

Dean Cumming's student and excavator, Emil Haury, closely examined scratches on the surface of the objects as they were removed from the ground and concluded that they were planted, based partly on a cavity in the ground which was longer than a lead bar removed from it. After Cummings became president of the university, his views changed in an unclear manner, possibly due to Haury's skepticism, or the increasing sentiment that the items were nothing more than a hoax and as university president had to take a different stand on the matter. George M. B. Hawley staunchly opposed Bent's views about the objects. Hawley even accused Ostrander and Sarle as perpetrators of the hoax. [3] [4]

A local news article identified Timoteo Odohui as the possible creator of the items. Odohui was a young Mexican sculptor who lived near the site in the 1880s. The article mentions his possible connection to the site and his ability to craft lead objects. Bent wrote that a craftsman in the area had recalled the boy, his love for sculpture of soft metals and his collection of books on foreign languages, and told the excavators this. [8] [5] [9]

H. P. Lovecraft alludes to the Tucson artifacts in "The Mound," a short story ghost-written for Zealia Bishop. [10] Archaeologist and Lovecraft scholar Marc A. Beherec argues that the items influenced some of Lovecraft's other writings. [9] [11]

The Tucson artifacts were featured on The History Channel show America Unearthed in the episode titled "The Desert Cross," on February 22, 2013. [12] This episode was criticised for its methodology, its ignorance (or deliberate omission) of the complete text on the crosses, and its conclusions. [13]

An out-of-place artifact is an artifact of historical, archaeological, or paleontological interest found in an unusual context, which challenges conventional historical chronology by its presence in that context. Such artifacts may appear too advanced for the technology known to have existed at the time, or may suggest human presence at a time before humans are known to have existed. Other examples may suggest contact between different cultures that is hard to account for with conventional historical understanding.

The Glozel artifacts are a collection of over 3,000 artifacts, including clay tablets, sculptures and vases, some of which were inscribed, discovered from 1924 to 1930 in the vicinity of French hamlet of Glozel. Glozel is part of the commune of Ferrières-sur-Sichon in the Allier department, some 17 km from Vichy in central France.

Mogollon culture is an archaeological culture of Native American peoples from Southern New Mexico and Arizona, Northern Sonora and Chihuahua, and Western Texas. The northern part of this region is Oasisamerica, while the southern span of the Mogollon culture is known as Aridoamerica.

The Hohokam Pima National Monument is an ancient Hohokam village within the Gila River Indian Community, near present-day Sacaton, Arizona. The monument features the archaeological site Snaketown 30 miles (48 km) southeast of Phoenix, Arizona, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964. The area was further protected by declaring it a national monument in 1972, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

The Amerind Foundation is a museum and research facility dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of Native American cultures and their histories. Its facilities are located near the village of Dragoon in Cochise County, Arizona, about 65 miles east of Tucson in Texas Canyon.

The National Archaeological Museum in Athens houses some of the most important artifacts from a variety of archaeological locations around Greece from prehistory to late antiquity. It is considered one of the greatest museums in the world and contains the richest collection of Greek Antiquity artifacts worldwide. It is situated in the Exarcheia area in central Athens between Epirus Street, Bouboulinas Street and Tositsas Street while its entrance is on the Patission Street adjacent to the historical building of the Athens Polytechnic university.

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums are a group of three archaeological museums located in the Eminönü quarter of Istanbul, Turkey, near Gülhane Park and Topkapı Palace.

The Newark Holy Stones refer to a set of artifacts allegedly discovered by David Wyrick in 1860 within a cluster of ancient Indian burial mounds near Newark, Ohio, now generally believed to be a hoax. The set consists of the Keystone, a stone bowl, and the Decalogue with its sandstone box. They can be viewed at the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum in Coshocton, Ohio. The site where the objects were found is known as The Newark Earthworks, one of the biggest collections from an ancient American Indian culture known as the Hopewell that existed from approximately 100 BC to AD 500.

The Mound is a horror/science fiction novella by American author H. P. Lovecraft, written by him as a ghostwriter from December 1929 to January 1930 after he was hired by Zealia Bishop to create a story about a Native American mound which is haunted by a headless ghost. Lovecraft expanded the story into a tale about a mound that conceals a gateway to a subterranean civilization, the realm of K'n-yan. The story was not published during Lovecraft's lifetime. A heavily abridged version was published in the November 1940 issue of Weird Tales, and the full text was finally published in 1989.

Emil Walter "Doc" Haury was an influential archaeologist who specialized in the archaeology of the American Southwest. He is most famous for his work at Snaketown, a Hohokam site in Arizona.

The Double Adobe site is an archaeological site in southern Arizona, twelve miles northwest of Douglas in the Whitewater Draw area. In October 1926, just three months after the first human artifact was uncovered at the Folsom site, Byron Cummings, first Head of the Archaeology Department at the University of Arizona, led four students to Whitewater Draw. Discovered by a schoolboy, the Double Adobe site contained the skull of a mammoth overlying a sand layer containing stone artifacts. One of these students was Emil Haury.

Pueblo Grande Ruin and Irrigation Sites are pre-Columbian archaeological sites and ruins, located in Phoenix, Arizona. They include a prehistoric platform mound and irrigation canals. The City of Phoenix manages these resources as the S’edav Va’aki Museum.

Ventana Cave is an archaeological site in southern Arizona. It is located on the Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation. The cave was excavated under the direction of Emil Haury by teams led by Julian Hayden in 1942, and in 1941 by a team led by Wilfrid C Bailey, one of Emil Haury's graduate students. The deepest artifacts from Ventana Cave were recovered from a layer of volcanic debris that also contained Pleistocene horse, Burden's pronghorn, tapir, sloth, and other extinct and modern species. A projectile point from the volcanic debris layer was compared to the Folsom Tradition and later to the Clovis culture, but the assemblage was peculiar enough to warrant a separate name – the Ventana Complex. Radiocarbon dates from the volcanic debris layer indicated an age of about 11,300 BP.

The Arizona State Museum (ASM), founded in 1893, was originally a repository for the collection and protection of archaeological resources. Today, however, ASM stores artifacts, exhibits them and provides education and research opportunities. It was formed by authority of the Arizona Territorial Legislature. The museum is operated by the University of Arizona, and is located on the university campus in Tucson.

The Naco Mammoth Kill Site is an archaeological site in southeast Arizona, 1 mile northwest of Naco in Cochise County. The site was reported to the Arizona State Museum in September 1951 by Marc Navarrete, a local resident, after his father found two Clovis points in Greenbush Draw, while digging out the fossil bones of a mammoth. Emil Haury excavated the Naco mammoth site in April 1952. In only five days, Haury recovered the remains of a Columbian Mammoth in association with 8 Clovis points. The excavator believed the assemblage to date from about 10,000 Before Present. An additional point was found in the arroyo upstream. The Naco site was the first Clovis mammoth kill association to be identified. An additional, unpublished, second excavation occurred in 1953 which doubled the area of the original work and found bones from a 2nd mammoth. In 2020, small charcoal fragments were found adhered to a mammoth bone from the site. AMS radiocarbon dating produced a mean date of 10,985 ± 56 Before Present.

Hyperdiffusionism is an archaeological hypothesis that postulates that certain historical technologies or ideas were developed by a single people or civilization and then spread to other cultures. Thus, all great civilizations that engaged in similar cultural practices, such as the construction of pyramids, derived them from a single common progenitor. According to proponents of hyperdiffusion, examples of hyperdiffusion can be found in religious practices, cultural technologies, megalithic monuments, and lost ancient civilizations.

The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology is a museum of archaeology located on the University of Michigan central campus in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the United States. The museum is a unit of the University of Michigan's College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. It has a collection of more than 100,000 ancient and medieval artifacts from the civilizations of the Mediterranean and the Near East. In addition to displaying its permanent and special exhibitions, the museum sponsors research and fieldwork and conducts educational programs for the public and for schoolchildren. The museum also houses the University of Michigan Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology.

Silver Bell is a ghost town in the Silver Bell Mountains in Pima County, Arizona, United States. The name "Silver Bell" refers to a more recent ghost town, which was established in 1954 and abandoned in 1984. The original town, established in 1904, was named "Silverbell" and abandoned in the early 1930s. Both towns were utilized and later abandoned due to the mining of copper in the area.

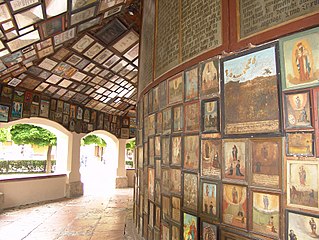

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally made in order to gain favor with supernatural forces.

Clara Lee Tanner was an American anthropologist, editor and art historian. She is known for studies of the arts and crafts of American Indians of the Southwest.

The manuscript’s age looked appallingly genuine ... It must be a shocking hoax ... Surely this was the clever forgery of some learned cynic — something like the leaden crosses in New Mexico, which a jester once planted and pretended to discover as a relique of some forgotten Dark Age colony from Europe.