The Bermuda Triangle, also known as the Devil's Triangle, is an urban legend focused on a loosely defined region in the western part of the North Atlantic Ocean where a number of aircraft and ships are said to have disappeared under mysterious circumstances. The idea of the area as uniquely prone to disappearances arose in the mid-20th century, but most reputable sources dismiss the idea that there is any mystery.

Q-ships, also known as Q-boats, decoy vessels, special service ships, or mystery ships, were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open fire and sink them.

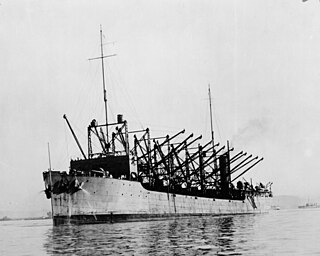

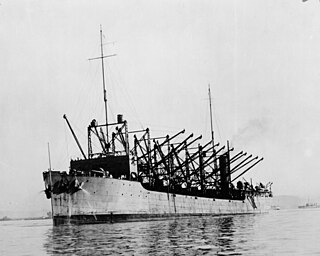

USS Langley (CV-1/AV-3) was the United States Navy's first aircraft carrier, converted in 1920 from the collier USS Jupiter, and also the US Navy's first turbo-electric-powered ship. Conversion of another collier was planned but canceled when the Washington Naval Treaty required the cancellation of the partially built Lexington-class battlecruisers Lexington and Saratoga, freeing up their hulls for conversion to the aircraft carriers Lexington and Saratoga. Langley was named after Samuel Langley, an American aviation pioneer. Following another conversion to a seaplane tender, Langley fought in World War II. On 27 February 1942, while ferrying a cargo of USAAF P-40s to Java, she was attacked by nine twin-engine Japanese bombers of the Japanese 21st and 23rd naval air flotillas and so badly damaged that she had to be scuttled by her escorts. She was also the only carrier of her class.

The second USS California (ACR-6), also referred to as "Armored Cruiser No. 6", and later renamed San Diego, was a United States Navy Pennsylvania-class armored cruiser.

USS Wasp (CV-7) was a United States Navy aircraft carrier commissioned in 1940 and lost in action in 1942. She was the eighth ship named USS Wasp, and the sole ship of a class built to use up the remaining tonnage allowed to the U.S. for aircraft carriers under the treaties of the time. As a reduced-size version of the Yorktown-class aircraft carrier hull, Wasp was more vulnerable than other United States aircraft carriers available at the opening of hostilities. Wasp was initially employed in the Atlantic campaign, where Axis naval forces were perceived as less capable of inflicting decisive damage. After supporting the occupation of Iceland in 1941, Wasp joined the British Home Fleet in April 1942 and twice ferried British fighter aircraft to Malta.

HMS Orion was a Leander-class light cruiser which served with distinction in the Royal Navy during World War II. She received 13 battle honours, a record only exceeded by HMS Warspite and matched by two others.

Flight 19 was the designation of a group of five General Motors TBM Avenger torpedo bombers that disappeared over the Bermuda Triangle on December 5, 1945, after losing contact during a United States Navy overwater navigation training flight from Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale, Florida. All 14 naval aviators on the flight were lost, as were all 13 crew members of a Martin PBM Mariner flying boat that subsequently launched from Naval Air Station Banana River to search for Flight 19.

USS Corry (DD-463), a Gleaves-class destroyer,, was the second ship of the United States Navy to be named for Lieutenant Commander William M. Corry, Jr., an officer in the Navy during World War I and a recipient of the Medal of Honor.

USS Hobson (DD-464/DMS-26), a Gleaves-class destroyer, was the only ship of the United States Navy to be named for Richmond Pearson Hobson, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions during the Spanish–American War. He would later in his career attain the rank of rear admiral and go on to serve as a congressman from the state of Alabama.

SM U-151 or SM Unterseeboot 151 was a World War I U-boat of the Imperial German Navy, constructed by Reiherstieg Schiffswerfte & Maschinenfabrik at Hamburg and launched on 4 April 1917. From 1917 until the Armistice in November 1918 she was part of the U-Kreuzer Flotilla, and was responsible for 34 ships sunk (88,395 GRT) and 7 ships damaged.

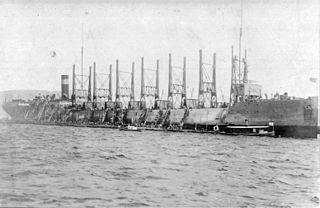

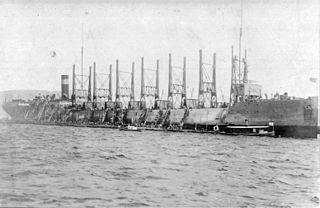

USS Nereus (AC-10) was one of four Proteus-class colliers built for the United States Navy before World War I. Named for Nereus, an aquatic deity from Greek mythology, she was the second U.S. Naval vessel to bear the name. Nereus was laid down on 4 December 1911, and launched on 26 April 1913 by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, Newport News, Virginia, and commissioned on 10 September 1913.

The collier USS Proteus (AC-9) was laid down on 31 October 1911, by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, and launched on 14 September 1912. She was the lead ship of her class of four colliers. She was commissioned on 9 July 1913, to the United States Navy.

USS Bayntun (DE-1) was the first of the American built lend lease Captain-class frigates in the Royal Navy as HMS Bayntun (K310). She was named for Henry William Bayntun.

HMSJuno was a 26-gun Spartan-class sixth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy launched in 1844 at Pembroke. As HMS Juno, she carried out the historic role in 1857 of annexing the Cocos (Keeling) Islands to the British Empire. She was renamed HMS Mariner in January 1878 and then HMS Atalanta two weeks later.

USS Orion (AC–11) was a collier of the United States Navy. The ship was laid down by the Maryland Steel Co., Sparrows Point, Maryland, on 6 October 1911, launched on 23 March 1912, and commissioned at Norfolk on 29 July 1912.

USS Hannibal (AG-1) was launched 9 March 1898 as the 1,785 GRT steamer Joseph Holland of London. The ship was laid down at as North Dock yard hull 143 for F. S. Holland, London, by J. Blumer & Company at Sunderland, England. Completion was in April 1898.

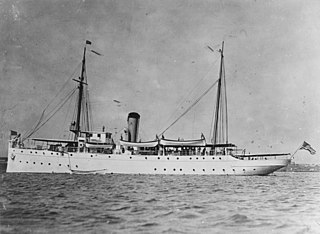

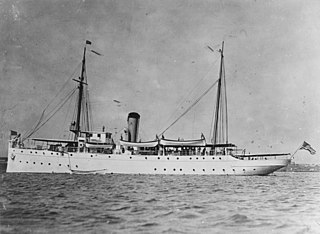

USCGC Tampa (ex-Miami) was a Miami-class cutter that initially served in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, followed by service in the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Navy. Tampa was used extensively on the International Ice Patrol and also during the Gasparilla Carnival at Tampa, Florida and other regattas as a patrol vessel. It was sunk with the highest American naval combat casualty loss in World War I.

USS Henry R. Mallory (ID-1280) was a transport for the United States Navy during World War I. She was also sometimes referred to as USS H. R. Mallory or as USS Mallory. Before her Navy service she was USAT Henry R. Mallory as a United States Army transport ship. From her 1916 launch, and after her World War I military service, she was known as SS Henry R. Mallory for the Mallory Lines. Pressed into service as a troopship in World War II by the War Shipping Administration, she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-402 in the North Atlantic Ocean and sank with the loss of 272 men—over half of those on board.

United States Navy operations during World War I began on April 6, 1917, after the formal declaration of war on the German Empire. The United States Navy focused on countering enemy U-boats in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea while convoying men and supplies to France and Italy. Because of United States's late entry into the war, her capital ships never engaged the German fleet and few decisive submarine actions occurred.