| Upper airway resistance syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | UARS, non-hypoxic sleep-disordered breathing |

Upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) is a sleep disorder characterized by the narrowing of the airway that can cause disruptions to sleep. [1] [2] The symptoms include unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, sleepiness, chronic insomnia, and difficulty concentrating. UARS can be diagnosed by polysomnograms capable of detecting Respiratory Effort-related Arousals. It can be treated with lifestyle changes, functional orthodontics, surgery, mandibular repositioning devices or CPAP therapy. [3] UARS is considered a variant of sleep apnea, [4] although some scientists and doctors believe it to be a distinct disorder. [5] [6]

Upper airway resistance syndrome was first recognized at Stanford University in the late 1980s. The article that described it by name, along with its relationship to obstructive sleep apnea, was published in 1992 by Guilleminault et al. [7]

Symptoms of UARS are similar to those of obstructive sleep apnea, but not inherently overlapping. Fatigue, insomnia, daytime sleepiness, unrefreshing sleep, anxiety, and frequent awakenings during sleep are the most common symptoms. Oxygen desaturation is minimal or absent in UARS, with most having a minimum oxygen saturation >92%. [8]

Many patients experience chronic insomnia that creates both a difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. As a result, patients typically experience frequent sleep disruptions. [9] Most patients with UARS snore, but not all. [4]

Some patients experience hypotension, which may cause lightheadedness, and patients with UARS are also more likely to experience headaches and irritable bowel syndrome. [9]

Predisposing factors include a high and narrow hard palate, an abnormally small intermolar distance, an abnormal overjet greater than or equal to 3 millimeters, and a thin soft palatal mucosa with a short uvula. In 88% of the subjects, there is a history of early extraction or absence of wisdom teeth. There is an increased prevalence of UARS in east Asians. [6]

Upper airway resistance syndrome is caused when the upper airway narrows without closing. Consequently, airflow is either reduced or compensated for through an increase in inspiratory efforts. This increased activity in inspiratory muscles leads to the arousals during sleep which patients may or may not be aware of. [1]

A typical UARS patient is not obese and possesses small jaws, which can result in a smaller amount of space in the nasal airway and behind the base of the tongue. [4] Patients may have other anatomical abnormalities that can cause UARS such as deviated septum, inferior turbinate hypertrophy, a narrow hard palate that reduces nasal volume, enlarged tonsils, or nasal valve collapse. [10] [2] UARS affects equal numbers of males and females. [1]

Why some patients with airway obstruction present with UARS and not OSA is thought to be caused by alterations in nerves located in the palatal mucosa. UARS patients have largely intact and responsive nerves, while OSA patients show clear impairment and nerve damage. Functioning nerves in the palatal mucosa allow UARS patients to more effectively detect and respond to flow limitations before apneas and hypopneas can occur. Patients with intact nerves are able to dilate the genioglossus muscle, a key compensatory mechanism utilized in the presence of airway obstruction. What damages the nerves is not definitively known, but it is hypothesized to be caused by the long term effects of gastroesophageal reflux and/or snoring. [11] [12]

UARS is diagnosed using the Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI). A patient is considered to have UARS when they have an Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) less than 5, but an RDI greater than or equal to 5. Unlike the Apnea-Hypopnea Index, the Respiratory Disturbance Index includes Respiratory Effort-related Arousals (RDI = AHI + RERA Index). [13] In 2005, the definition of sleep apnea was changed to include patients with UARS by using RDI to determine sleep apnea severity.

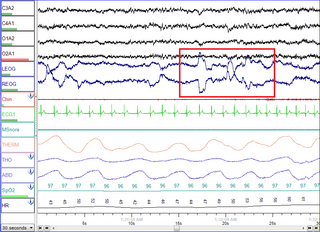

The diagnosis of UARS is based on findings on a polysomnogram. On polysomnograms, a UARS patient will have very few apneas and hypopneas, but many Respiratory effort-related Arousals.

More recently, it has become increasingly more common for doctors to utilize portable Home Sleep Test monitors (HST) for the diagnosis of sleep – related breathing problems when insurance will not approve polysomnography. Some of the HSTs allow for the breathing signals to be viewed within the raw data of the HST study and even a cursory review of these flow signals, will reveal those patients who would likely have upper airway resistance syndrome as well. RERAs are periods of increased respiratory effort lasting for more than ten seconds and ending in arousal. Whether or not an event is classified as a RERA or Hypopnea depends on the definition of Hypopnea used by the sleep technician. [13] The American Academy of Sleep Medicine currently recognizes two definitions. The scoring of Respiratory Effort-related Arousals is currently designated as "optional" by the AASM. Thus, many patients who receive sleep studies may receive a negative result, even if they have UARS. [14]

Based on symptoms, patients are commonly misdiagnosed with idiopathic insomnia, idiopathic hypersomnia, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, or a psychiatric disorder such as ADHD or depression. [9] Studies have found that children with UARS are frequently misdiagnosed with ADHD. One study found UARS or OSA present in up to 56% of children with ADHD. [15] Studies show that symptoms of ADHD caused by UARS significantly improve or remit with treatment in surgically treated children. [16]

Behavioral modifications include getting at least 7–8 hours of sleep and various lifestyle changes, such as positional therapy. [17] Sleeping on one's side rather than in a supine position or using positional pillows can provide relief, but these modifications may not be sufficient to treat more severe cases. [17] Avoiding sedatives including alcohol and narcotics can help prevent the relaxation of airway muscles, and thereby reduce the chance of their collapse. Avoiding sedatives may also help to reduce snoring. [17]

Nasal steroids may be prescribed in order to ease nasal allergies and other obstructive nasal conditions that could cause UARS. [17]

If left untreated, UARS can develop into obstructive sleep apnea. Treatments for OSA such as positive airway pressure therapy can be effective at stopping the progression of UARS. [18] [19] Positive airway pressure therapy is similar to that in obstructive sleep apnea and works by stenting the airway open with pressure, thus reducing the airway resistance. Use of a CPAP can help ease the symptoms of UARS. Therapeutic trials have shown that using a CPAP with pressure between four and eight centimeters of water can help to reduce the number of arousals and improve sleepiness. [4] CPAPs are the most promising treatment for UARS, but effectiveness is reduced by low patient compliance. [20]

Oral appliances to protrude the tongue and lower jaw forward have been used to reduce sleep apnea and snoring, and hold potential for treating UARS, but this approach remains controversial. [20] Oral appliances may be a suitable alternative for patients who cannot tolerate CPAP. [17]

For nasal obstruction, options can be septoplasty, turbinate reductions, or surgical palate expansion. [2]

Orthognathic surgeries that expands the airway, such as Maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) or Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (SARPE) are the most effective surgeries for sleep disordered breathing.

Though less common methods of treatment, various surgical options including uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), hyoid suspension, and linguloplasty exist. These procedures increase the dimensions of the upper airway and reduce the collapsibility of the airway. [3] One should also be screened for the presence of a hiatal hernia, which may result in abnormal pressure differentials in the esophagus, and in turn, constricted airways during sleep. [3] Palatal tissue reduction via radiofrequency ablation has also been successful in treating UARS. [20]

Orthodontic treatment to expand the volume of the nasal airway, such as nonsurgical Rapid Palatal expansion is common in children. [21] [17] Due to the ossification of the median palatine suture, traditional tooth-born expanders cannot achieve maxillary expansion in adults as the mechanical forces instead tip the teeth and dental alveoli. Mini-implant assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) has been recently developed as a minimally invasive option for the transverse expansion of the maxilla in adults. [22] This method increases the volume of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, leading to increased airflow and reduced respiratory arousals during sleep. [23]

Sleep apnea, also spelled sleep apnoea, is a sleep disorder in which pauses in breathing or periods of shallow breathing during sleep occur more often than normal. Each pause can last for a few seconds to a few minutes and they happen many times a night. In the most common form, this follows loud snoring. A choking or snorting sound may occur as breathing resumes. Because the disorder disrupts normal sleep, those affected may experience sleepiness or feel tired during the day. In children, it may cause hyperactivity or problems in school.

Snoring is the vibration of respiratory structures and the resulting sound due to obstructed air movement during breathing while sleeping. The sound may be soft or loud and unpleasant. Snoring during sleep may be a sign, or first alarm, of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Research suggests that snoring is one of the factors of sleep deprivation.

Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) is a condition in which severely overweight people fail to breathe rapidly or deeply enough, resulting in low oxygen levels and high blood carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. The syndrome is often associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which causes periods of absent or reduced breathing in sleep, resulting in many partial awakenings during the night and sleepiness during the day. The disease puts strain on the heart, which may lead to heart failure and leg swelling.

Positive airway pressure (PAP) is a mode of respiratory ventilation used in the treatment of sleep apnea. PAP ventilation is also commonly used for those who are critically ill in hospital with respiratory failure, in newborn infants (neonates), and for the prevention and treatment of atelectasis in patients with difficulty taking deep breaths. In these patients, PAP ventilation can prevent the need for tracheal intubation, or allow earlier extubation. Sometimes patients with neuromuscular diseases use this variety of ventilation as well. CPAP is an acronym for "continuous positive airway pressure", which was developed by Dr. George Gregory and colleagues in the neonatal intensive care unit at the University of California, San Francisco. A variation of the PAP system was developed by Professor Colin Sullivan at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, Australia, in 1981.

Hypersomnia is a neurological disorder of excessive time spent sleeping or excessive sleepiness. It can have many possible causes and can cause distress and problems with functioning. In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), hypersomnolence, of which there are several subtypes, appears under sleep-wake disorders.

Polysomnography (PSG), a type of sleep study, is a multi-parameter study of sleep and a diagnostic tool in sleep medicine. The test result is called a polysomnogram, also abbreviated PSG. The name is derived from Greek and Latin roots: the Greek πολύς, the Latin somnus ("sleep"), and the Greek γράφειν.

A mandibi splint or mandibi advancement splint is a prescription custom-made medical device worn in the mouth used to treat sleep-related breathing disorders including: obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), snoring, and TMJ disorders. These devices are also known as mandibular advancement devices, sleep apnea oral appliances, oral airway dilators, and sleep apnea mouth guards.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common sleep-related breathing disorder and is characterized by recurrent episodes of complete or partial obstruction of the upper airway leading to reduced or absent breathing during sleep. These episodes are termed "apneas" with complete or near-complete cessation of breathing, or "hypopneas" when the reduction in breathing is partial. In either case, a fall in blood oxygen saturation, a disruption in sleep, or both, may result. A high frequency of apneas or hypopneas during sleep may interfere with the quality of sleep, which – in combination with disturbances in blood oxygenation – is thought to contribute to negative consequences to health and quality of life. The terms obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) or obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) may be used to refer to OSA when it is associated with symptoms during the daytime.

Hypopnea is overly shallow breathing or an abnormally low respiratory rate. Hypopnea is defined by some to be less severe than apnea, while other researchers have discovered hypopnea to have a "similar if not indistinguishable impact" on the negative outcomes of sleep breathing disorders. In sleep clinics, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome or obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome is normally diagnosed based on the frequent presence of apneas and/or hypopneas rather than differentiating between the two phenomena. Hypopnea is typically defined by a decreased amount of air movement into the lungs and can cause oxygen levels in the blood to drop. It commonly is due to partial obstruction of the upper airway.

When we sleep, our breathing changes due to normal biological processes that affect both our respiratory and muscular systems.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a form of positive airway pressure (PAP) ventilation in which a constant level of pressure greater than atmospheric pressure is continuously applied to the upper respiratory tract of a person. The application of positive pressure may be intended to prevent upper airway collapse, as occurs in obstructive sleep apnea, or to reduce the work of breathing in conditions such as acute decompensated heart failure. CPAP therapy is highly effective for managing obstructive sleep apnea. Compliance and acceptance of use of CPAP therapy can be a limiting factor, with 8% of people stopping use after the first night and 50% within the first year.

The respiratory disturbance index (RDI)—or respiratory distress Index—is a formula used in reporting polysomnography findings. Like the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), it reports on respiratory distress events during sleep, but unlike the AHI, it also includes respiratory-effort related arousals (RERAs). RERAs are arousals from sleep that do not technically meet the definitions of apneas or hypopneas, but do in some way disrupt breathing during sleep and cause respiratory symptoms that may cause an arousal.

Catathrenia or nocturnal groaning is a sleep-related breathing disorder, consisting of end-inspiratory apnea and expiratory groaning during sleep. It describes a rare condition characterized by monotonous, irregular groans while sleeping. Catathrenia begins with a deep inspiration. The person with catathrenia holds her or his breath against a closed glottis, similar to the Valsalva maneuver. Expiration can be slow and accompanied by sound caused by vibration of the vocal cords or a simple rapid exhalation. Despite a slower breathing rate, no oxygen desaturation usually occurs. The moaning sound is usually not noticed by the person producing the sound, but it can be extremely disturbing to sleep partners. It appears more often during expiration REM sleep than in NREM sleep.

Christian Guilleminault was a French physician and researcher in the field of sleep medicine who played a central role in the early discovery of obstructive sleep apnea and made seminal discoveries in many other areas of sleep medicine.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) or central sleep apnea syndrome (CSAS) is a sleep-related disorder in which the effort to breathe is diminished or absent, typically for 10 to 30 seconds either intermittently or in cycles, and is usually associated with a reduction in blood oxygen saturation. CSA is usually due to an instability in the body's feedback mechanisms that control respiration. Central sleep apnea can also be an indicator of Arnold–Chiari malformation.

Nasal expiratory positive airway pressure is a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and snoring.

A sleep-related breathing disorder is a sleep disorder in which abnormalities in breathing occur during sleep that may or may not be present while awake. According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, sleep-related breathing disorders are classified as follows:

Sleep surgery is a surgery performed to treat sleep disordered breathing. Sleep disordered breathing is a spectrum of disorders that includes snoring, upper airway resistance syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea. These surgeries are performed by surgeons trained in otolaryngology, oral maxillofacial surgery, and craniofacial surgery.

A high-arched palate is where the palate is unusually high and narrow. It is usually a congenital developmental feature that results from the failure of the palatal shelves to fuse correctly in development, the same phenomenon that leads to cleft palate. It may occur in isolation or in association with a number of conditions. It may also be an acquired condition caused by chronic thumb-sucking. A high-arched palate may result in a narrowed airway and sleep disordered breathing.

Alexander Adu Clerk, is a Ghanaian American academic, psychiatrist and sleep medicine specialist who was the Director of the world's first sleep medical clinic, the Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine from 1990 to 1998. Clerk is also a Fellow of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)