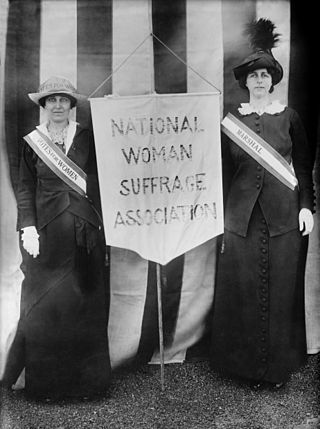

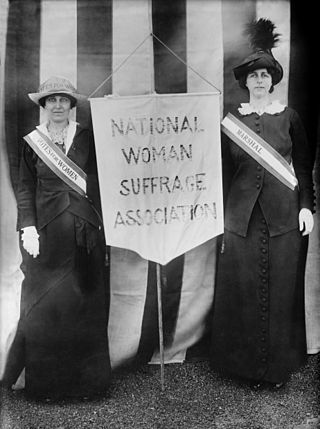

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement split over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution, which would in effect extend voting rights to black men. One wing of the movement supported the amendment while the other, the wing that formed the NWSA, opposed it, insisting that voting rights be extended to all women and all African Americans at the same time.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

Women's legal right to vote was established in the United States over the course of more than half a century, first in various states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920 with the passing of the 19th Amendment.

The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was a single-issue national organization formed in 1869 to work for women's suffrage in the United States. The AWSA lobbied state governments to enact laws granting or expanding women's right to vote in the United States. Lucy Stone, its most prominent leader, began publishing a newspaper in 1870 called the Woman's Journal. It was designed as the voice of the AWSA, and it eventually became a voice of the women's movement as a whole.

Ida Husted Harper was an American author, journalist, columnist, and suffragist, as well as the author of a three-volume biography of suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony at Anthony's request. Harper also co-edited and collaborated with Anthony on volume four (1902) of the six-volume History of Woman Suffrage and completed the project by solo writing volumes five and six (1922) after Anthony's death. In addition, Harper served as secretary of the Indiana chapter of the National Woman Suffrage Association, became a prominent figure in the women's suffrage movement in the U.S., and wrote columns on women's issues for numerous newspapers across the United States. Harper traveled extensively, delivered lectures in support of women's rights, handled press relations for a women's suffrage amendment in California, headed the National American Woman Suffrage Association's national press bureau in New York City and the editorial correspondence department of the Leslie Bureau of Suffrage Education in Washington, D.C., and chaired the press committee of the International Council of Women.

The College Equal Suffrage League (CESL) was an American woman suffrage organization founded in 1900 by Maud Wood Park and Inez Haynes Irwin, as a way to attract younger Americans to the women's rights movement. The League spurred the creation of college branches around the country and influenced the actions of other prominent groups such as National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

The Georgia Woman Suffrage Association was the first women's suffrage organization in the U.S. state of Georgia. It was founded in 1890 by Helen Augusta Howard (1865-1934). It was affiliated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Ellen Battelle Dietrick (1847–1895) was an American suffragist and author who was active in the movement's organizations in Kentucky and Massachusetts. She was a core member of the group that published The Woman's Bible in the 1890s.

Lucy Elmina Anthony was an internationally known leader in the American woman's suffrage movement. She was the niece of American social reformer and women's rights activist, Susan B. Anthony, and longtime companion of women's suffrage leader, Anna Howard Shaw. She served as a secretary to both women, as well as on the committee on local arrangements for the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA)

Lenna Lowe Yost, president of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association (WVESA) during the state woman suffrage referendum campaign of 1916 and chairman of the WVESA Ratification Committee during the national amendment ratification campaign of 1920. Yost was at the time also the state president of the West Virginia Woman's Christian Temperance Union, thus being the only woman in the nation to serve as both president of temperance and of the suffrage club at the same time. Yost was the first woman to be appointed to the state Board of Education, and the first woman to chair the West Virginia Republic Party convention.

Anna Beulah Boyd Ritchie was a founding member of the Fairmont Woman Suffrage Club, third president of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association, and officer in the West Virginia Woman's Christian Temperance Union.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Missouri. Women's suffrage in Missouri started in earnest after the Civil War. In 1867, one of the first women's suffrage groups in the U.S. was formed, called the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri. Suffragists in Missouri held conventions, lobbied the Missouri General Assembly and challenged the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). The case that went to SCOTUS in 1874, Minor v. Happersett was not ruled in the suffragists' favor. Instead of challenging the courts for suffrage, Missouri suffragists continued to lobby for changes in legislation. In April 1919, they gained the right to vote in presidential elections. On July 3, 1919, Missouri becomes the eleventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Virginia. While there were some very early efforts to support women's suffrage in Virginia, most of the activism for the vote for women occurred early in the 20th century. The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was formed in 1909 and the Virginia Branch of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage was formed in 1915. Over the next years, women held rallies, conventions and many propositions for women's suffrage were introduced in the Virginia General Assembly. Virginia didn't ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952. Native American women could not have a full vote until 1924 and African American women were effectively disenfranchised until the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Georgia. Women's suffrage in Georgia started in earnest with the formation of the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA) in 1892. GWSA helped bring the first large women's rights convention to the South in 1895 when the National American Woman's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) held their convention in Atlanta. GWSA was the main source of activism behind women's suffrage until 1913. In that year, several other groups formed including the Georgia Young People's Suffrage Association (GYPSA) and the Georgia Men's League for Woman Suffrage. In 1914, the Georgia Association Opposed to Women's Suffrage (GAOWS) was formed by anti-suffragists. Despite the hard work by suffragists in Georgia, the state continued to reject most efforts to pass equal suffrage. In 1917, Waycross, Georgia allowed women to vote in primary elections and in 1919 Atlanta granted the same. Georgia was the first state to reject the Nineteenth Amendment. Women in Georgia still had to wait to vote statewide after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified on August 26, 1920. Native American and African American women had to wait even longer to vote. Georgia ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in 1970.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Illinois. Women's suffrage in Illinois began in the mid 1850s. The first women's suffrage group was created in 1855 in Earlville, Illinois by Susan Hoxie Richardson. The Illinois Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), later renamed the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA), was created by Mary Livermore in 1869. This group held annual conventions and petitioned various governmental bodies in Illinois for women's suffrage. On June 19, 1891, women gained the right to vote for school offices. However, it wasn't until 1913 that women saw expanded suffrage. That year women in Illinois were granted the right to vote for Presidential electors and various local offices. Suffragists continued to fight for full suffrage in the state. Finally, Illinois became the first state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on June 10, 1919. The League of Women Voters (LWV) was announced in Chicago on February 14, 1920.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Alabama. Women's suffrage in Alabama starts in the late 1860s and grows over time in the 1890s. Much of the women's suffrage work stopped after 1901, only to pick up again in 1910. Alabama did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1953 and African-Americans and women were affected by poll taxes and other issues until the mid 1960s.

Women's suffrage in Nevada began in the late 1860s. Lecturer and suffragist, Laura de Force Gordon, started giving women's suffrage speeches in the state starting in 1867. In 1869, Assemblyman Curtis J. Hillyer introduced a women's suffrage resolution in the Nevada Legislature. He also spoke out on women's rights. Hillyer's resolution passed, but like all proposed amendments to the state constitution, must pass one more time and then go out to a voter referendum. In 1870, Nevada held its first women's suffrage convention in Battle Mountain Station. In the late 1880s, women gained the right to run for school offices and the next year several women are elected to office. A few suffrage associations were formed in the mid 1890s, with a state group operating a few women's suffrage conventions. However, after 1899, most suffrage work slowed down or stopped altogether. In 1911, the Nevada Equal Franchise Society (NEFS) was formed. Attorney Felice Cohn wrote a women's suffrage resolution that was accepted and passed the Nevada Legislature. The resolution passed again in 1913 and will go out to the voters on November 3, 1914. Suffragists in the state organized heavily for the 1914 vote. Anne Henrietta Martin brought in suffragists and trade unionists from other states to help campaign. Martin and Mabel Vernon traveled around the state in a rented Ford Model T, covering thousands of miles. Suffragists in Nevada visited mining towns and even went down into mines to talk to voters. On November 3, the voters of Nevada voted overwhelmingly for women's suffrage. Even though Nevada women won the vote, they did not stop campaigning for women's suffrage. Nevada suffragists aided other states' campaigns and worked towards securing a federal suffrage amendment. On February 7, 1920, Nevada became the 28th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Maine. Suffragists began campaigning in Maine in the mid 1850s. A lecture series was started by Ann F. Jarvis Greely and other women in Ellsworth, Maine in 1857. The first women's suffrage petition to the Maine Legislature was sent that same year. Women continue to fight for equal suffrage throughout the 1860s and 1870s. The Maine Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) is established in 1873 and the next year, the first Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) chapter was started. In 1887, the Maine Legislature votes on a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution, but it does not receive the necessary two-thirds vote. Additional attempts to pass women's suffrage legislation receives similar treatment throughout the rest of the century. In the twentieth century, suffragists continue to organize and meet. Several suffrage groups form, including the Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League in 1914 and the Men's Equal Suffrage League of Maine in 1914. In 1917, a voter referendum on women's suffrage is scheduled for September 10, but fails at the polls. On November 5, 1919 Maine ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment. On September 13, 1920, most women in Maine are able to vote. Native Americans in Maine are barred from voting for many years. In 1924, Native Americans became American citizens. In 1954, a voter referendum for Native American voting rights passes. The next year, Lucy Nicolar Poolaw (Penobscot), is the Native American living on an Indian reservation to cast a vote.

Frances Ellen Burr was an American suffragist and writer from Connecticut.