Ulysses S. Grant was an American military officer, politician, and the 18th president of the United States, who served from 1869 to 1877. As commanding general, Grant led the Union Army to victory in the American Civil War in 1865 and briefly served as U.S. secretary of war. An effective civil rights executive, Grant signed a bill to create the Justice Department and worked with Radical Republicans to protect African Americans during Reconstruction.

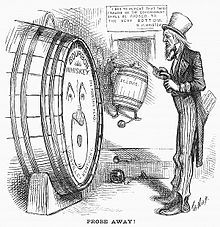

The Whiskey Rebellion was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax imposed on a domestic product by the newly formed federal government. Beer was difficult to transport and spoiled more easily than rum and whiskey. Rum distillation in the United States had been disrupted during the American Revolutionary War, and whiskey distribution and consumption increased afterwards. The "whiskey tax" became law in 1791, and was intended to generate revenue to pay the war debt incurred during the Revolutionary War. The tax applied to all distilled spirits, but consumption of American whiskey was rapidly expanding in the late 18th century, so the excise became widely known as a "whiskey tax". Farmers of the western frontier were accustomed to distilling their surplus rye, barley, wheat, corn, or fermented grain mixtures to make whiskey. These farmers resisted the tax. In these regions, whiskey often served as a medium of exchange. Many of the resisters were war veterans who believed that they were fighting for the principles of the American Revolution, in particular against taxation without local representation, while the federal government maintained that the taxes were the legal expression of Congressional taxation powers.

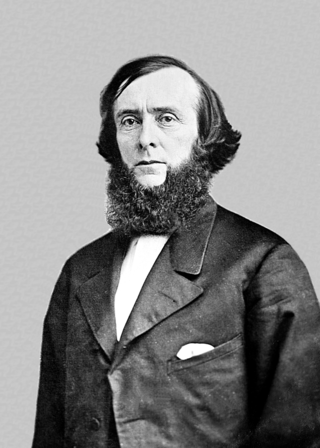

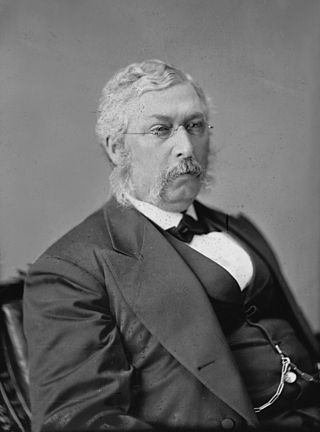

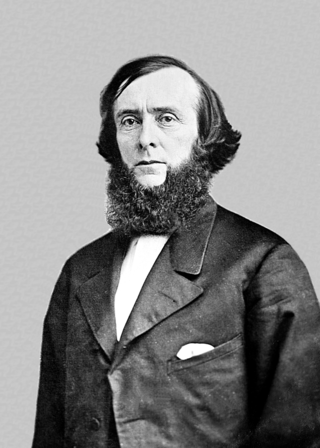

Lot Myrick Morrill was an American politician who served as the 28th governor of Maine, as a United States senator, and as U.S. secretary of the treasury under President Ulysses S. Grant. An advocate for hard currency rather than paper money, Morrill was popularly received as treasury secretary by the American press and Wall Street. He was known for financial and political integrity, and was said to be focused on serving the public good rather than party interests. Morrill was President Grant's fourth and last Secretary of the Treasury.

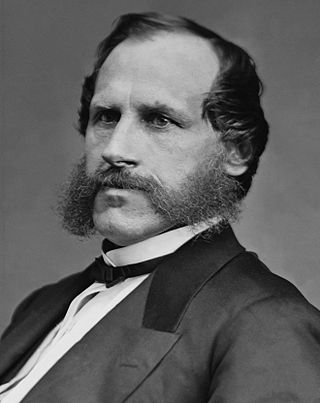

Benjamin Helm Bristow was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first Solicitor General.

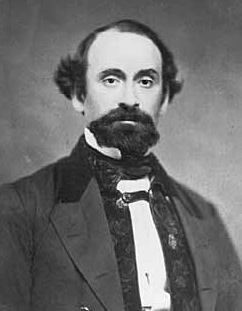

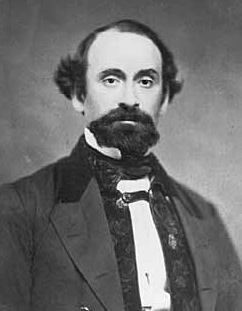

Edwards Pierrepont was an American attorney, reformer, jurist, traveler, New York U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Minister to England, and orator. Having graduated from Yale in 1837, Pierrepont studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1840. During the American Civil War, Pierrepont was a Democrat, although he supported President Abraham Lincoln. Pierrepont initially supported President Andrew Johnson's conservative Reconstruction efforts having opposed the Radical Republicans. In both 1868 and 1872, Pierrepont supported Ulysses S. Grant for president. For his support, President Grant appointed Pierrepont United States Attorney in 1869. In 1871, Pierrepont gained the reputation as a solid reformer, having joined New York's Committee of Seventy that shut down Boss Tweed's corrupt Tammany Hall. In 1872, Pierrepont modified his views on Reconstruction and stated that African American freedman's rights needed to be protected.

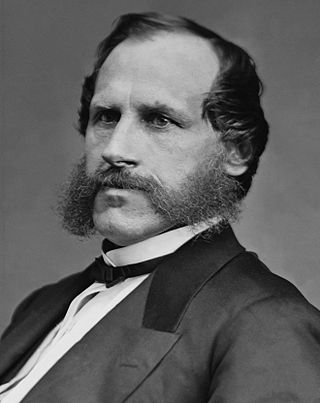

Marshall Jewell was a manufacturer, pioneer telegrapher, telephone entrepreneur, world traveler, and political figure who served as 44th and 46th Governor of Connecticut, the US Minister to Russia, the 25th United States Postmaster General, and Republican Party National Chairman. Jewell, distinguished for his fine "china" skin, grey eyes, and white eyebrows, was popularly known as the "Porcelain Man". As Postmaster General, Jewell made reforms and was intent on cleaning up the Postal Service from internal corruption and profiteering. Postmaster Jewell helped Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin H. Bristow shut down and prosecute the Whiskey Ring. President Grant, however, became suspicious of Jewell's loyalty after Jewell fired a Boston postmaster over non payment of a surety bond and asked for his resignation.

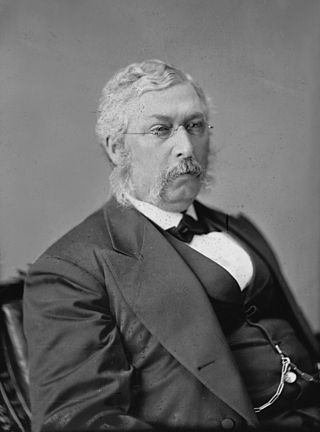

Columbus Delano was an American lawyer, rancher, banker, statesman, and a member of the prominent Delano family. Forced to live on his own at an early age, Delano struggled to become a self-made man. Delano was elected U.S. Congressman from Ohio, serving two full terms and one partial one. Prior to the American Civil War, Delano was a National Republican and then a Whig; as a Whig, he was identified with the faction of the party that opposed the spread of slavery into the Western territories. He became a Republican when the party was founded as the major anti-slavery party after the demise of the Whigs in the 1850s. During Reconstruction Delano advocated federal protection of African-Americans' civil rights, and argued that the former Confederate states should be administered by the federal government, but not as part of the United States until they met the requirements for readmission to the Union.

George Henry Williams was an American judge and politician. He served as chief justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, was the 32nd Attorney General of the United States, and was elected Oregon's U.S. senator, and served one term. Williams, as U.S. senator, authored and supported legislation that allowed the U.S. military to be deployed in Reconstruction of the southern states to allow for an orderly process of re-admittance into the United States. Williams was the first presidential Cabinet member to be appointed from the Pacific Coast. As attorney general under President Ulysses S. Grant, Williams continued the prosecutions that shut down the Ku Klux Klan. He had to contend with controversial election disputes in Reconstructed southern states. President Grant and Williams legally recognized P. B. S. Pinchback as the first African American state governor. Williams ruled that the Virginius, a gun-running ship delivering men and munitions to Cuban revolutionaries, which was captured by Spain during the Virginius Affair, did not have the right to bear the U.S. flag. However, he also argued that Spain did not have the right to execute American crew members. Nominated for Supreme Court Chief Justice by President Grant, Williams failed to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate primarily due to Williams's opposition to U.S. Attorney A. C. Gibbs, his former law partner, who refused to stop investigating Republican fraud in the special congressional election that resulted in a victory for Democrat James Nesmith.

The Sanborn incident or Sanborn contract was an American political scandal which occurred in 1874. William Adams Richardson, President Ulysses S. Grant's Secretary of the Treasury, hired a private citizen, John B. Sanborn, a former Union General, to collect $427,000 in unpaid taxes. Richardson agreed Sanborn could keep half of what he collected. After extorting money from companies to pay back taxes by falsely making claims of tax evasion, Sanborn kept $213,000, of which $156,000 went to his various assistants. After an investigation by the Treasury Department discovered corruption, President Grant signed legislation making the practice illegal.

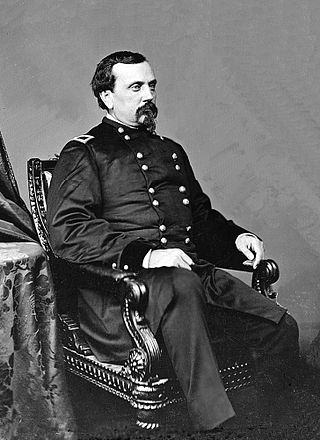

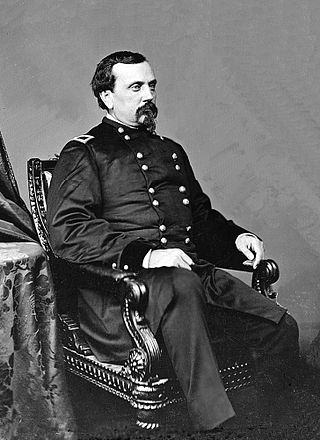

George Maxwell Robeson was an American politician and lawyer from New Jersey. A brigadier general in the New Jersey Militia during the American Civil War, he served as Secretary of the Navy, appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant, from 1869 to 1877. A member of the Republican Party, he also served two terms as a U.S. Representative for New Jersey from 1879 to 1883.

Orville Elias Babcock was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secretary at the White House, Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds for Washington D.C., and a Florida-based federal inspector of lighthouses. Babcock continued to serve as lighthouse inspector under Grant's successors Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Chester A. Arthur.

Grantism is a derisive term of United States origin referring to the political incompetence, corruption, and fraud, during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant. His presidency, which lasted from 1869 to 1877, was marred by many scandals and fraudulent activities associated with persons within his administration, including his cabinet, which was in continual transition, divided by the forces of political corruption and reform. Among them were: Black Friday, corruption in the Department of the Interior, the Sanborn incident, and the Whiskey Ring.

Ulysses S. Grant and his administration, including his cabinet, suffered many scandals, leading to a continuous reshuffling of officials. Grant, ever trusting of his chosen associates, had strong bonds of loyalty to those he considered friends. Grant was influenced by political forces of both reform and corruption. The standards in many of his appointments were low, and charges of corruption were widespread At times, however, Grant appointed various cabinet members who helped clean up the executive corruption. Starting with the Black Friday (1869) gold speculation ring, corruption would be discovered in seven federal departments. The Liberal Republicans, a political reform faction that bolted from the Republican Party in 1871, attempted to defeat Grant for a second term in office, but the effort failed. Taking over the House in 1875, the Democratic Party had more success in investigating, rooting out, and exposing corruption in the Grant Administration. Nepotism, although legally unrestricted at the time, was prevalent, with over 40 family members benefiting from government appointments and employment. In 1872, Senator Charles Sumner, labeled corruption in the Grant administration "Grantism."

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The Ku Klux Klan caused widespread violence throughout the South against African Americans. By 1870, all former Confederate states had been readmitted into the United States and were represented in Congress; however, Democrats and former slave owners refused to accept that freedmen were citizens who were granted suffrage by the Fifteenth Amendment, which prompted Congress to pass three Force Acts to allow the federal government to intervene when states failed to protect former slaves' rights. Following an escalation of Klan violence in the late 1860s, Grant and his attorney general, Amos T. Akerman, head of the newly created Department of Justice, began a crackdown on Klan activity in the South, starting in South Carolina, where Grant sent federal troops to capture Klan members. This led the Klan to demobilize and helped ensure fair elections in 1872.

During Ulysses S. Grant's two terms as president of the United States (1869–1877) there were several executive branch investigations, prosecutions, and reforms carried-out by President Grant, Congress, and several members of his cabinet, in the wake of several revelations of fraudulent activities within the administration. Grant's cabinet fluctuated between talented individuals or reformers and those involved with political patronage or party corruption. Some notable reforming cabinet members were persons who had outstanding abilities and made many positive contributions to the administration. These reformers resisted the Republican Party's demands for patronage to select efficient civil servants. Although Grant traditionally is known for his administration scandals, more credit has been given to him for his appointment of reformers.

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th president of the United States (1869–1877) following his success as military commander in the American Civil War. Under Grant, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and secession, the war ending with the surrender of Robert E. Lee's army at Appomattox Court House. As president, Grant led the Radical Republicans in their effort to eliminate vestiges of Confederate nationalism and slavery, protect African American citizenship, and pursued Reconstruction in the former Confederate states. In foreign policy, Grant sought to increase American trade and influence, while remaining at peace with the world. Although his Republican Party split in 1872 as reformers denounced him, Grant was easily reelected. During his second term the country's economy was devastated by the Panic of 1873, while investigations exposed corruption scandals in the administration. Although still below average, his reputation among scholars has significantly improved in recent years because of greater appreciation for his commitment to civil rights, moral courage in his prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan, and enforcement of voting rights.

President Ulysses S. Grant signed a series of laws during his first and second terms that limited the number of special tax agents and prevented or reduced the collection of delinquent taxes under a commissions or moiety system. The public outcry over the Sanborn incident caused the Grant administration to abolish the practice of appointing special treasury agents to collect commissions or moieties on delinquent taxes.

President Ulysses S. Grant sympathized with the plight of Native Americans and believed that the original occupants of the land were worthy of study. Grant's Inauguration Address set the tone for the Grant administration Native American Peace policy. The Board of Indian Commissioners was created to make reforms in Native policy and to ensure Native tribes received federal help. Grant lobbied the United States Congress to ensure that Native peoples would receive adequate funding. The hallmark of Grant's Peace policy was the incorporation of religious groups that served on Native agencies, which were dispersed throughout the United States.

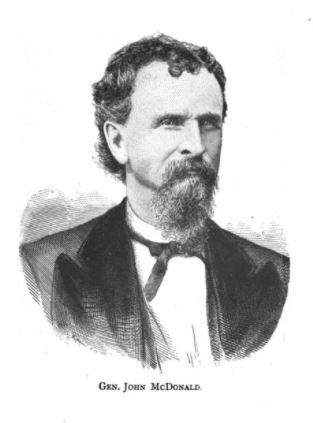

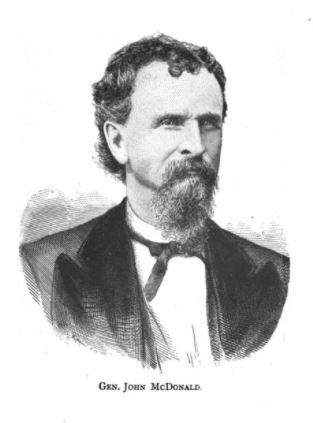

John McDonald was born in Rochester, New York, on February 22, 1832. At the age of nine, he was orphaned. To support himself, McDonald worked a series of odd jobs on canals, lakes, and rivers. He arrived in St. Louis at the age of 15. McDonald worked his way up in responsible river trade jobs. By the 1850s he was a passenger agent for a St. Louis steam company. Eventually, he started his own business, running a freight steamer that carried passengers on the Missouri River. At the outbreak of the Civil War, McDonald was a strong Union man. Appointed a Major rank, McDonald raised and outfitted the Eighth Regiment that served in battles at Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, and Shiloh. President Abraham Lincoln appointed him a Brigadier General. McDonald kept the title of "General" for the rest of his life.

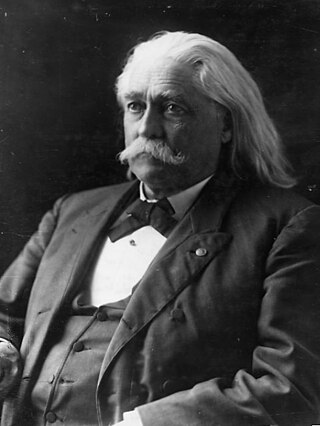

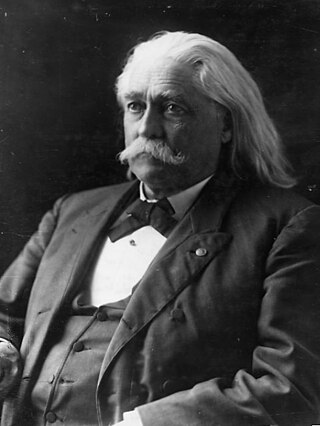

John Alexander Joyce was an Irish–American poet and writer. He served as a first lieutenant and regimental adjutant in the Union Army. He was indicted for his role as Internal Revenue Service agent in the Whiskey Ring.