Related Research Articles

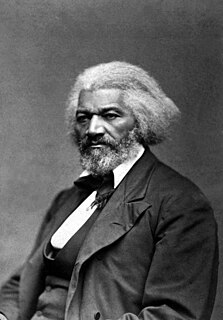

Frederick Douglass was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, becoming famous for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings. Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counterexample to slaveholders' arguments that slaves lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. Likewise, Northerners at the time found it hard to believe that such a great orator had once been a slave.

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society, who often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown, also a freedman, also often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had 1,350 local chapters with around 250,000 members.

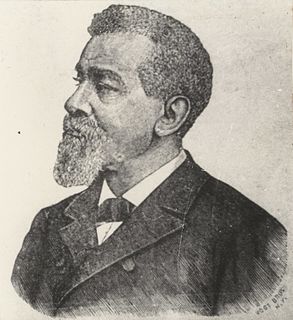

Henry Highland Garnet was an African-American abolitionist, minister, educator and orator. Having escaped with his family as a child from slavery in Maryland, he grew up in New York City. He was educated at the African Free School and other institutions, and became an advocate of militant abolitionism. He became a minister and based his drive for abolitionism in religion.

James McCune Smith was an American physician, apothecary, abolitionist, and author in New York City. He was the first African American to hold a medical degree and graduated at the top in his class at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. After his return to the United States, he became the first African American to run a pharmacy in the nation.

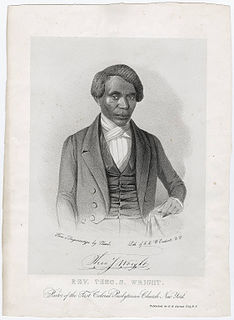

Theodore Sedgwick Wright (1797–1847), sometimes Theodore Sedgewick Wright, was an African-American abolitionist and minister who was active in New York City, where he led the First Colored Presbyterian Church as its second pastor. He was the first African American to attend Princeton Theological Seminary, from which he graduated in 1828 or 1829. In 1833 he became a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, an interracial group that included Samuel Cornish, a black Presbyterian, and many Congregationalists, and served on its executive committee until 1840.

Amos Noë Freeman (1809—1893) was an African-American abolitionist, Presbyterian minister, and educator. He was the first full-time minister of Abyssinian Congregational Church in Portland, Maine, where he led a station on the Underground Railroad, and served for decades at Siloam Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, New York.

Alexander Crummell was a pioneering African-American minister, academic and African nationalist. Ordained as an Episcopal priest in the United States, Crummell went to England in the late 1840s to raise money for his church by lecturing about American slavery. Abolitionists supported his three years of study at Cambridge University, where Crummell developed concepts of pan-Africanism.

The North Star was a nineteenth-century anti-slavery newspaper published from the Talman Building in Rochester, New York, by abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The paper commenced publication on December 3, 1847, and ceased as The North Star in June 1851, when it merged with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper. At the time of the Civil War, it was Douglass' Monthly.

Beriah Green, Jr. was an American reformer, abolitionist, temperance advocate, college professor, minister, and head of the Oneida Institute. He was "consumed totally by his abolitionist views". He has been described as "cantankerous". Former student Alexander Crummell described him as a "bluff, kind-hearted man," a "master-thinker".

The National Equal Rights League (NERL) is the oldest nationwide human rights organization in the United States. It was founded in Syracuse, New York in 1864 dedicated to the liberation of black people in the United States. Its origins can be traced back to the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies in 1833. The league emphasized moral reform and self-help, aiming "to encourage sound morality, education, temperance, frugality, industry, and promote everything that pertains to a well-ordered and dignified life." Black leaders formed state and local branches of the league which drew many members, which caused the society to grow quickly, in areas such as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where people such as Thomas Morris Chester joined.

The Noyes Academy was a racially integrated school, which also admitted women, founded by New England abolitionists in 1835 in Canaan, New Hampshire, near Dartmouth College, whose then-abolitionist president, Nathan Lord, was "the only seated New England college president willing to admit black students to his college".

William Cooper Nell was an African-American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for the integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Writing for abolitionist newspapers The Liberator and The North Star, he helped publicize the anti-slavery cause. He published the North Star from 1847 to 18xx, moving temporarily to Rochester, New York.

The Liberty Party was a minor political party in the United States in the 1840s. The party was an early advocate of the abolitionist cause and it broke away from the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) to advocate the view that the Constitution was an anti-slavery document. William Lloyd Garrison, leader of the AASS, held the contrary view, that the Constitution should be condemned as an evil pro-slavery document. The party included abolitionists who were willing to work within electoral politics to try to influence people to support their goals. By contrast, the radical Garrison opposed voting and working within the system. Many Liberty Party members joined the anti-slavery Free Soil Party in 1848 and eventually helped establish the Republican Party in the 1850s.

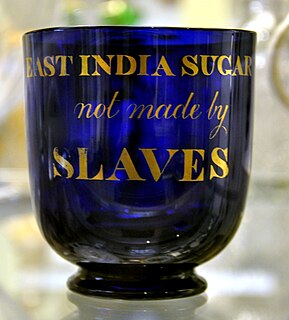

The free-produce movement was an international boycott of goods produced by slave labor. It was used by the abolitionist movement as a non-violent way for individuals, including the disenfranchised, to fight slavery.

Abolitionism in the United States was a movement that sought to end gradually or immediately slavery in the United States. It was active from the late colonial era until the American Civil War, which brought about the abolition of American slavery through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The anti-slavery movement originated during the Age of Enlightenment, focused on ending the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In Colonial America, a few German Quakers issued the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery, which marks the beginning of the American abolitionist movement. Before the Revolutionary War, evangelical colonists were the primary advocates for the opposition to slavery and the slave trade, doing so on humanitarian grounds. James Oglethorpe, the founder of the colony of Georgia, originally tried to prohibit slavery upon its founding, a decision that was eventually reversed.

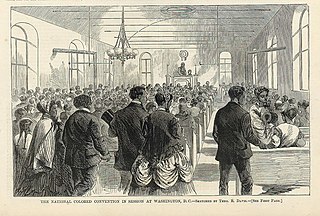

The Colored Conventions Movement, or Negro Convention Movement, was a series of national, regional, and state conventions held irregularly during the decades preceding and following the American Civil War. The delegates who attended these conventions consisted of both free and fugitive African Americans including religious leaders, businessmen, politicians, writers, publishers, and abolitionists. The conventions provided "an organizational structure through which black men could maintain a distinct black leadership and pursue black abolitionist goals."

William Gustavus Allen was an African-American academic, intellectual, and lecturer. For a time he co-edited The National Watchman, an abolitionist newspaper. While studying law in Boston he lectured widely on abolition, equality, and integration. He was then appointed a professor of rhetoric and Greek at New-York Central College, the second African-American college professor in the United States. He saw himself as an academic and intellectual.

George T. Downing was an abolitionist and activist for African-American civil rights while building a successful career as a restaurateur in New York City; Newport, Rhode Island; and Washington, DC. His father had been an oyster seller and caterer in Philadelphia and New York City, building a business that attracted wealthy white clients. From the 1830s until the end of slavery, Downing was active in the Underground Railroad, using his restaurant as a rest station for refugees on the move. He built a summer season business in Newport, and made it his home. For more than 10 years, he worked to integrate Rhode Island public schools. During the American Civil War (1861-1865), Downing helped recruit African-American soldiers.

The National Convention of Colored Citizens was held August 15–19, 184 at the Park Presbyterian Church in Buffalo, New York. Similar to previous colored conventions, the convention of 1843 was an assembly for African American citizens to discuss the organized efforts of the anti-slavery movement. The convention included individuals and delegates from various states and cities. Henry Garnet and Samuel Davis delivered key speeches. Delegates deliberated courses of action and voted upon resolutions to further anti-slavery efforts and to help African Americans.

References

- ↑ Ripley, C. Peter (1985). The Black Abolitionist Papers: The United States, 1830-1846. UNC Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8078-1926-5.

- ↑ WM, Nell (Nov 9, 1847). "REPORT OF THE DOINGS OF THE NATIONAL CONVENTION OF COLORED AMERICANS AND THEIR FRIENDS, HELD AT TROY, N. Y., OCT. 6, 1847.: Presented to a Meeting held in Boston, Monday Evening, Oct. 25th, by WM. C. NELL". Liberator.

- ↑ Proceedings of the National Convention of Colored People, and Their Friends Held in Troy N.Y on the 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th October, 1847. Troy, N.Y. 1847.

- ↑ Comminey, Shawn C. (2015). "National Black Conventions and the Quest for African American Freedom and Progress, 1847-1867". International Social Science Review. 91 (1): 1–18. ISSN 0278-2308. JSTOR intesociscierevi.91.1.02.

- ↑ Eckel, Leslie (2013-02-28). Atlantic Citizens. Edinburgh University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7486-6939-4.