Related Research Articles

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership of property and the distribution of resources.

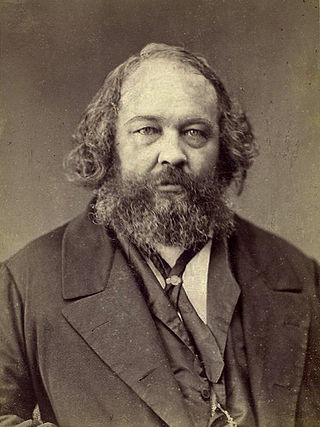

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, social anarchist, and collectivist anarchist traditions. Bakunin's prestige as a revolutionary also made him one of the most famous ideologues in Europe, gaining substantial influence among radicals throughout Russia and Europe.

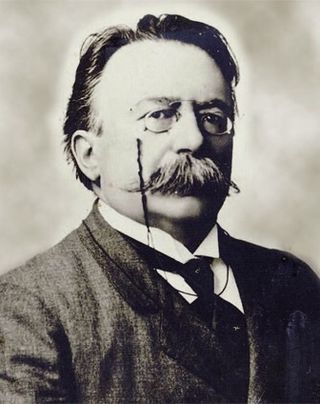

Errico Malatesta was an Italian anarchist propagandist, theorist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from Italy, Britain, France, and Switzerland. Originally a supporter of insurrectionary propaganda by deed, Malatesta later advocated for syndicalism. His exiles included five years in Europe and 12 years in Argentina. Malatesta participated in actions including an 1895 Spanish revolt and a Belgian general strike. He toured the United States, giving lectures and founding the influential anarchist journal La Questione Sociale. After World War I, he returned to Italy where his Umanità Nova had some popularity before its closure under the rise of Mussolini.

Gaetano Bresci was an Italian anarchist who assassinated the king Umberto I of Italy. As a young weaver, his experiences with exploitation in the workplace drew him to anarchism. Bresci emigrated to the United States, where he became involved with other Italian immigrant anarchists in Paterson, New Jersey. News of the Bava Beccaris massacre motivated him to return to Italy, where he planned to assassinate Umberto. Local police knew of his return but did not mobilize. Bresci killed the king in July 1900 during Umberto's scheduled appearance in Monza amid a sparse police presence.

Propaganda of the deed, or propaganda by the deed, is a type of direct action intended to influence public opinion. The action itself is meant to serve as an example for others to follow, acting as a catalyst for social revolution.

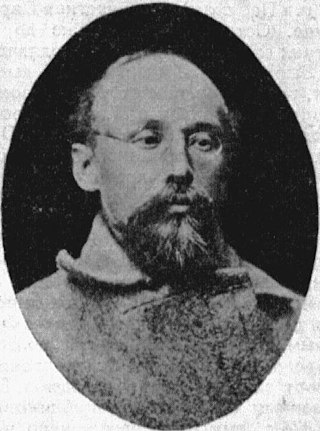

Giuseppe Fanelli was an Italian revolutionary anarchist, best known for his tour of Spain in 1868, introducing the anarchist ideas of Mikhail Bakunin.

Andrea Costa was an Italian politician, among the founders of socialism in Italy, and the first socialist deputy in Italian history. He was also initiated on September 25, 1883 to the Masonic Lodge "Rienzi" in Rome and progressively become 32nd-degree Mason and adjunctive Great Master of the Grande Oriente of Italy.

According to different scholars, the history of anarchism either goes back to ancient and prehistoric ideologies and social structures, or begins in the 19th century as a formal movement. As scholars and anarchist philosophers have held a range of views on what anarchism means, it is difficult to outline its history unambiguously. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined movement stemming from 19th-century class conflict, while others identify anarchist traits long before the earliest civilisations existed.

Luigi Galleani was an Italian insurrectionary anarchist best known for his advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", a strategy of political assassinations and violent attacks.

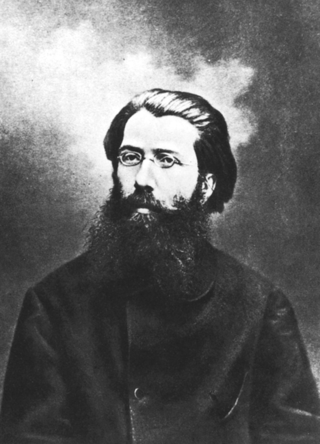

Carlo Cafiero was an Italian anarchist that led the Italian section of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA). An early leader of the Marxist and anarchist communist movements in Italy, he was a key influence in the development of both currents.

Anarchism in Russia developed out of the populist and nihilist movements' dissatisfaction with the government reforms of the time.

Italian anarchism as a movement began primarily from the influence of Mikhail Bakunin, Giuseppe Fanelli, Carlo Cafiero, and Errico Malatesta. Rooted in collectivist anarchism and social or socialist anarchism, it expanded to include illegalist individualist anarchism, mutualism, anarcho-syndicalism, and especially anarcho-communism. In fact, anarcho-communism first fully formed into its modern strain within the Italian section of the First International. Italian anarchism and Italian anarchists participated in the biennio rosso and survived Italian Fascism, with Italian anarchists significantly contributing to the Italian Resistance Movement. Platformism and insurrectionary anarchism have long been particularly common in Italian anarchism and continue to influence the movement today. The synthesist Italian Anarchist Federation and insurrectionary Informal Anarchist Federation appeared after the war, and autonomismo and operaismo especially influenced Italian anarchism in the second half of the 20th century.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to anarchism:

The Italian Revolutionary Socialist Party was a socialist political party in Italy.

Emilio Covelli (1846–1915) was an Italian anarchist and socialist who together with Carlo Cafiero was one of the most important figures in the early socialist movement in Italy, a member of the International Workingmen's Association, or "First International". He lived in exile in Paris for a while, returning to Italy for reasons of health, and dying in the psychiatric hospital in Nocera Inferiore.

La Plebe was an Italian newspaper that was published in Lodi from 1868 to 1875, then in Milan from 1875 to 1883. The editor was Enrico Bignami.

Lodovico Nabruzzi was an Italian journalist and anarchist. He played a leading role in the dissensions between the revolutionary and evolutionary Italian socialists. He spent several years in exile in Switzerland and France, often forced to undertake menial work and often in trouble with the authorities. After returning to Italy his life continued to be difficult, and he suffered from mental health problems. Although he married and had four children the marriage did not last. He died alone in a public hospital.

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based on a political program and periodic congresses. Instead, insurrectionary anarchists advocate informal organization and small affinity group based organization. Insurrectionary anarchists put value in attack, permanent class conflict and a refusal to negotiate or compromise with class enemies.

Mikhail Petrovich Sazhin, also known by the pseudonym Armand Ross, was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. An activist during his years as a student, he was expelled and exiled for his revolutionary activities, forcing him to flee the country to Switzerland, where he became a disciple of the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. During the 1870s, he participated in a series of uprisings, including those of the Lyon and Paris Communes, the 1874 Bologna insurrection and Herzegovina uprising, before returning to Russia in order to ignite an insurrection there. He was arrested for smuggling revolutionary literature across the border and tried as part of the Trial of the 193, which resulted in him getting exiled to Siberia. He spent the subsequent decades working in a number of steamship companies throughout Russia, eventually returning to European Russia and participating in a number of radical publishing ventures. He spent his final years in Moscow, attempting to publish Bakunin's literary works and working as an activist for the Society of Former Political Prisoners and Exiled Settlers.

Olimpiada Evgrafovna Kutuzova, also known as Olimpia Kutuzova Cafiero, was a Russian Narodnik. Facing arrest for her revolutionary activities, she married the Italian anarchist Carlo Cafiero in order to seek political asylum abroad. After a year in exile, she returned to Russia, where she educated peasant children and participated in the Going to the People movement, which brought her again to the attention of authorities.

References

- ↑ Drake 2009, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 Drake 2009, p. 36.

- ↑ Pernicone 1993, p. 85.