Rosa Luxemburg was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, orthodox Marxist, and anti-War activist during the First World War. She became a key figure of the revolutionary socialist movements of Poland and Germany during the late 19th and early 20th century, particularly the Spartacist uprising.

The Communist Party of Germany was a major far-left political party in the Weimar Republic during the interwar period, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West Germany during the postwar period until it was banned by the Federal Constitutional Court in 1956.

The German revolution of 1918–1919, also known as the November Revolution, was an uprising started by workers and soldiers in the final days of World War I. It quickly and almost bloodlessly brought down the German Empire, then, in its more violent second stage, the supporters of a parliamentary republic were victorious over those who wanted a Soviet-style council republic. The defeat of the forces of the far left cleared the way for the establishment of the Weimar Republic. The key factors leading to the revolution were the extreme burdens suffered by the German people during the war, the economic and psychological impacts of the Empire's defeat, and the social tensions between the general populace and the aristocratic and bourgeois elite.

Leon "Leo" Jogiches, also commonly known by the party name Jan Tyszka, was a Polish Marxist revolutionary and politician, active in Poland, Lithuania, and Germany.

A union representative, union steward, or shop steward is an employee of an organization or company who represents and defends the interests of their fellow employees as a trades/labour union member and official. Rank-and-file members of the union hold this position voluntarily while maintaining their role as an employee of the firm. As a result, the union steward becomes a significant link and conduit of information between the union leadership and rank-and-file workers.

Social patriotism is an openly patriotic standpoint which combines patriotism with socialism. It was first identified at the outset of the First World War when a majority of Social Democrats opted to support the war efforts of their respective governments and abandoned socialist internationalism and worker solidarity.

The Free Association of German Trade Unions was a trade union federation in Imperial and early Weimar Germany. It was founded in 1897 in Halle under the name Representatives' Centralization of Germany as the national umbrella organization of the localist current of the German labor movement. The localists rejected the centralization in the labor movement following the sunset of the Anti-Socialist Laws in 1890 and preferred grassroots democratic structures. The lack of a strike code soon led to conflict within the organization. Various ways of providing financial support for strikes were tested before a system of voluntary solidarity was agreed upon in 1903, the same year that the name Free Association of German Trade Unions was adopted.

Emil Barth was a German Social Democratic party worker and socialist politician who became a key figure in the German Revolution of 1918.

Richard Müller was a German socialist, metal worker, union shop steward, and later historian. Trained as a lathe-operator, Müller later became an industrial unionist and organizer of mass-strikes against World War I. In 1918 he was a leading figure of the council movement in the German Revolution. In the 1920s he wrote a three-volume history of the German Revolution.

Events in the year 1916 in Germany.

During the First World War (1914–1918), the Revolutionary Stewards were shop stewards who were independent from the official unions and freely chosen by workers in various German industries. They rejected the war policies of the German Empire and the support which parliamentary representatives of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) gave to the policies. They also played a role during the German Revolution of 1918–19.

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht was a German revolutionary socialist and anti-militarist. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) beginning in 1900, he was one of its deputies in the Reichstag from 1912 to 1916, where he represented the left-revolutionary wing of the party. In 1916 he was expelled from the SPD's parliamentary group for his opposition to the Burgfriedenspolitik, the political truce between all parties in the Reichstag while the war lasted. He twice spent time in prison, first for writing an anti-militarism pamphlet in 1907 and then for his role in a 1916 antiwar demonstration. He was released from the second under a general amnesty three weeks before the end of the First World War.

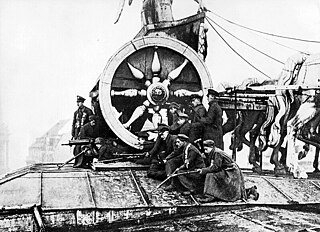

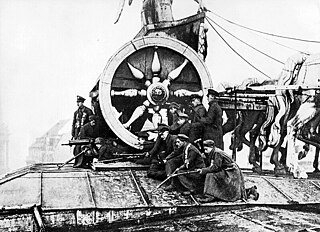

The Spartacist uprising, also known as the January uprising or, more rarely, Bloody Week, was an armed uprising that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the German revolution that broke out just before the end of World War I. The uprising was primarily a power struggle between the supporters of the provisional government led by Friedrich Ebert of the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD), which favored a social democracy, and those who backed the position of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, which wanted to set up a council republic similar to the one established by the Bolsheviks in Russia. The government's forces were victorious in the fighting.

A workers' council, also called labor council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of political and economic organization, the workers themselves are able to exercise decision-making power. Furthermore, the workers within each council decide on what their agenda is and what their needs are. The council communist Antonie Pannekoek describes shop-committees and sectional assemblies as the basis for workers' management of the industrial system. A variation is a soldiers' council, where soldiers direct a mutiny. Workers and soldiers have also operated councils in conjunction. Workers' councils may in turn elect delegates to central committees, such as the Congress of Soviets.

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions of political, social, and labour organizations and may also include rallies, marches, boycotts, civil disobedience, non-payment of taxes, and other forms of direct or indirect action. Additionally, general strikes might exclude care workers, such as teachers, doctors, and nurses.

The Spartacus League was a Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. It was founded in August 1914 as the International Group by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, and other members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) who were dissatisfied with the party's official policies in support of the war. In 1916 it renamed itself the Spartacus Group and in 1917 joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), which had split off from the SPD as its left wing faction.

The Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany was the name officially used by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) between April 1917 and September 1922. The name differentiated it from the Independent Social Democratic Party, which split from the SPD as a result of the party majority's support of the government during the First World War.

The German strike of January 1918 was a strike against World War I which spread across the German Empire. It lasted from 25 January to 1 February 1918. It is known as the "Januarstreik", as distinct from the "Jännerstreik" which preceded it spreading across Austria-Hungary between January 3 and 25, 1918. The strike began in Berlin on 28 January and spread across the rest of Germany, but finally collapsed. The strike was caused by food shortages, war weariness and the October Revolution in Russia, which raised the hopes of revolutionary Marxists in Germany. The strike was conceived by the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany or USPD, whose left wing, the Spartacus League was now agitating for political revolution in order to end the war. While the strikes were triggered by the earlier "Jännerstreik" in Austria, the widespread response in Germany signaled the USPD's growing importance in German politics. At its height the strike involved over a million people in important industrial regions such as Kiel, Hamburg, Mannheim, and Augsburg, only being shut down when the military arrested or impressed the strike leaders, sending them to the front lines.

August Ernst Reinhold Merges was a German activist, politician and revolutionary. He was a member of various communist and syndicalist organisations; becoming one of the leaders of the German Revolution in Braunschweig, and subsequently a member of the Weimar National Assembly, convened in 1919 to draw up a constitution for the new German republic. In 1933, he came to the notice of the authorities as a "background member" of an anti-government resistance group. In 1945, after he was found dead in the little summer-hut in his son's allotment it was determined that ever since undergoing a succession of severe torture sessions at the hands of the security services during and after 1935, he had suffered without a break from the bone tuberculosis that killed him. His name is accordingly listed on the "Reichstag Memorial" to the 96 members of the parliament who died "unnaturally" during the twelve Hitler years.

The German workers' and soldiers' councils of 1918–1919 were short-lived revolutionary bodies that spread the German Revolution to cities across the German Empire during the final days of World War I. Meeting little to no resistance, they formed quickly, took over city governments and key buildings, caused most of the locally stationed military to flee and brought about the abdications of all of Germany's ruling monarchs, including Emperor Wilhelm II when they reached Berlin on 9 November 1918.