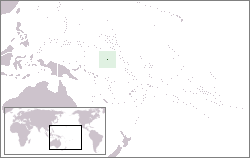

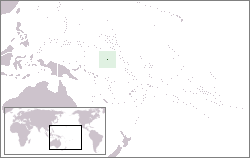

Nauru, officially the Republic of Nauru and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Micronesia, part of Oceania in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba of Kiribati, about 300 km (190 mi) to the east. It lies northwest of Tuvalu, 1,300 km (810 mi) northeast of Solomon Islands, east-northeast of Papua New Guinea, southeast of the Federated States of Micronesia and south of the Marshall Islands. With an area of only 21 km2 (8.1 sq mi), Nauru is the third-smallest country in the world behind Vatican City and Monaco, making it the smallest republic as well as the smallest island nation. Its population of about 10,000 is the world's second-smallest, after Vatican City.

The history of human activity in Nauru, an island country in the Pacific Ocean, began roughly 3,000 years ago when clans settled the island.

The demographics of Nauru, an island country in the Pacific Ocean, are known through national censuses, which have been analysed by various statistical bureaus since the 1920s. The Nauru Bureau of Statistics have conducted this task since 1977—the first census since Nauru gained independence in 1968. The most recent census of Nauru was in 2011, when population had reached ten thousand. The population density is 478 inhabitants per square kilometre, and the overall life expectancy is 59.7 years. The population rose steadily from the 1960s until 2006 when the Government of Nauru repatriated thousands of Tuvaluan and I-Kiribati workers from the country. Since 1992, Nauru's birth rate has exceeded its death rate; the natural growth rate is positive. In terms of age structure, the population is dominated by the 15–64-year-old segment (65.6%). The median age of the population is 21.5, and the estimated gender ratio of the population is 0.91 males per one female.

Reverend Philip Adam Delaporte was a German-born American Protestant missionary who ran a mission on Nauru with his wife from 1899 until 1915. During this time he translated numerous texts from German into Nauruan including the Bible and a hymnal. He was also one of the first to create a written form for the Nauruan dialect, published in a Nauruan-German dictionary.

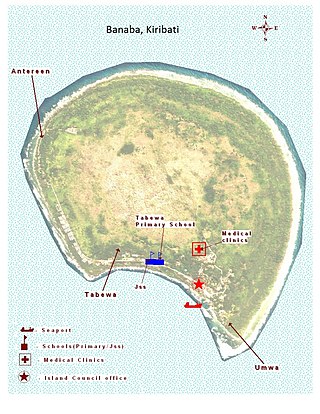

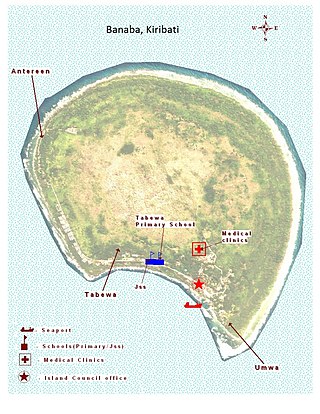

Banaba is an island of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean. A solitary raised coral island west of the Gilbert Island Chain, it is the westernmost point of Kiribati, lying 185 miles (298 km) east of Nauru, which is also its nearest neighbour. It has an area of six square kilometres (2.3 sq mi), and the highest point on the island is also the highest point in Kiribati, at 81 metres (266 ft) in height. Along with Nauru and Makatea, it is one of the important elevated phosphate-rich islands of the Pacific.

The displacement of the traditional culture of Nauru by contemporary western influences is evident on the island. Little remains from the old customs. The traditions of arts and crafts are nearly lost.

Timothy Detudamo was a Nauruan politician and linguist. He served as Head Chief of Nauru from 1930 until his death in 1953.

European exploration and settlement of Oceania began in the 16th century, starting with the Spanish (Castilian) landings and shipwrecks in the Mariana Islands, east of the Philippines. This was followed by the Portuguese landing and settling temporarily in some of the Caroline Islands and Papua New Guinea. Several Spanish landings in the Caroline Islands and New Guinea came after. Subsequent rivalry between European colonial powers, trade opportunities and Christian missions drove further European exploration and eventual settlement. After the 17th century Dutch landings in New Zealand and Australia, with no settlement in these lands, the British became the dominant colonial power in the region, establishing settler colonies in what would become Australia and New Zealand, both of which now have majority European-descended populations. States including New Caledonia (Caldoche), Hawaii, French Polynesia and Norfolk Island also have considerable European populations. Europeans remain a primary ethnic group in much of Oceania, both numerically and economically.

Sir Albert Fuller Ellis was a prospector in the Pacific. He discovered phosphate deposits on the Pacific islands of Nauru and Banaba in 1900. He was the British Phosphate Commissioner for New Zealand from 1921 to 1951.

The British Phosphate Commissioners (BPC) was a board of Australian, British, and New Zealand representatives who managed extraction of phosphate from Christmas Island, Nauru, and Banaba from 1920 until 1981.

Nauruan nationality law is regulated by the 1968 Constitution of Nauru, as amended; the Naoero Citizenship Act of 2017, and its revisions; custom; and international agreements entered into by the Nauruan government. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Nauru. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nauruan nationality is typically obtained either on the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in the Nauru or under the rules of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth to parents with Nauruan nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Raymond Gadabu was a Nauruan politician who served as Head Chief between 1953 and 1955.

The German attacks on Nauru refers to the two attacks on Nauru in December 1940. Nauru is an island country in Micronesia, a subregion of Oceania, in the Central Pacific. These attacks were conducted by auxiliary cruisers between 6 and 8 December and on 27 December. The raiders sank five Allied merchant ships and inflicted serious damage on Nauru's economically important phosphate-loading facilities. Despite the significance of the island to the Australian and New Zealand economies, Nauru was not defended and the German force did not suffer any losses.

The economy of Banaba and Nauru has been almost wholly dependent on phosphate, which has led to environmental disaster on these islands, with 80% of the islands’ surface having been strip-mined. The phosphate deposits were virtually exhausted by 2000, although some small-scale mining is still in progress on Nauru. Mining ended on Banaba in 1979.

The Japanese occupation of Nauru was the period of three years during which Nauru, a Pacific island under Australian administration, was occupied by the Japanese military as part of its operations in the Pacific War during World War II. With the onset of the war, the islands that flanked Japan's South Seas possessions became of vital concern to Japanese Imperial General Headquarters, and in particular to the Imperial Navy, which was tasked with protecting Japan's outlying Pacific territories.

Elections for the Local Government Council were held for the first time in Nauru on 15 December 1951.

Elections for the Legislative Council for the Territory of Nauru were held for the first and only time on 22 January 1966.

Constitutional Convention elections were held in Nauru on 19 December 1967.

Frederick Royden Chalmers, was an Australian farmer, soldier, businessman, and government administrator. His murder by Japanese soldiers on Nauru in 1943 was the focus of a war crimes trial following the Second World War.

The Nauru Local Government Council was a legislative body in Nauru. It was first established in 1951, when Nauru was a United Nations trust territory, as a successor to the Council of Chiefs. It continued to exist until 1992, when it was dissolved in favor of the Nauru Island Council.