Palar is a river of southern India. It rises in the Nandi Hills in Chikkaballapura district of Karnataka state, and flows 93 kilometres (58 mi) in Karnataka, 33 kilometres (21 mi) in Andhra Pradesh and 222 kilometres (138 mi) in Tamil Nadu before reaching its confluence into the Bay of Bengal at Vayalur about 75 kilometres (47 mi) south of Chennai. It flows as an underground river for a long distance only to emerge near Bethamangala town, from where, gathering water and speed, it flows eastward down the Deccan Plateau. The Towns of Bethamangala, Santhipuram, Kuppam,Mottur, Ramanaickenpet, Vaniyambadi, Ambur, Melpatti, Gudiyatham, Pallikonda, Anpoondi, Melmonavoor, Vellore, Katpadi, Melvisharam, Arcot, Ranipet, Walajapet, Kanchipuram, Walajabad, Chengalpattu, Kalpakkam, and Lattur are located on the banks of the Palar River. Of the seven tributaries, the chief tributary is the Cheyyar River.

Chembarambakkam lake is a lake located in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, about 25 km from Chennai. It is one of the two rain-fed reservoirs that supply water to Chennai City, the other one being the Puzhal Lake. The Adyar River originates from this lake. A part of water supply of the metropolis of Chennai is drawn from this lake. This was the first Artificial lake built by Rajendra Chola I the son of Rajaraja Chola and Thiripuvana Madeviyar, prince of Kodumbalur.

Sholavaram aeri, or Sholavaram lake, is located in Ponneri taluk of Thiruvallur district, Tamil Nadu, India. It is one of the rain-fed reservoirs from where water is drawn for supply Chennai city from this lake to Puzhal lake through canals.

Pulhal Lake, or Pulhal aeri, sometimes spelled Puzhal lake and also known as the Red Hills Lake, is located in Red Hills, Chennai, India. It lies in Thiruvallur district of Tamil Nadu state. It is one of the two rain-fed reservoirs that supply water to Chennai City, the other one being the Chembarambakkam Lake and Porur Lake.

Chennai is located at 13.04°N 80.17°E on the southeast coast of India and in the northeast corner of Tamil Nadu. It is located on a flat coastal plain known as the Eastern Coastal Plains. The city has an average elevation of 6 metres (20 ft), its highest point being 60 m (200 ft). Chennai is 2,184 kilometres south of Delhi, 1,337 kilometres southeast of Mumbai, and 1,679 kilometers southwest of Kolkata by road.

The Telugu Ganga project is a joint water supply scheme implemented in 1980s by the then Andhra Pradesh chief minister Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao and Tamil Nadu chief minister Maruthur Gopalan Ramachandran to provide drinking water to Chennai City in Tamil Nadu. It is also known as the Krishna Water Supply Project, since the source of the water is the Krishna River in erstwhile Andhra Pradesh. Water is drawn from the Srisailam reservoir and diverted towards Chennai through a series of interlinked canals, over a distance of about 406 kilometres (252 mi), before it reaches the destination at the Poondi reservoir near Chennai. The main checkpoints en route include the Somasila reservoir in Penna River valley, the Kandaleru reservoir, the 'Zero Point' near Uthukkottai where the water enters Tamil Nadu territory and finally, the Poondi reservoir, also known as Satyamurthy Sagar. From Poondi, water is distributed through a system of link canals to other storage reservoirs located at Red Hills, Sholavaram and Chembarambakkam.

Ambattur aeri, or Ambattur lake, is a rain-fed reservoir which reaches top levels during the monsoon seasons. In November 2008, incessant monsoon rain filled the lake and encroachments on the north and south banks of the lake were demolished. It also caters to the drinking water needs of the Chennai city after Poondi and Chembarambakkam Lake.

Tamil Nadu is the tenth largest state in India and covers an area of 130,058 square kilometres (50,216 sq mi). It is bordered by Kerala to the west, Karnataka to the northwest, Andhra Pradesh to the north, the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Indian Ocean to the south. Cape Comorin (Kanyakumari), the southernmost tip of the Indian Peninsula which is the meeting point of the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the Indian Ocean is located in Tamil Nadu.

Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board, known shortly as CMWSSB, is a statutory board of Government of Tamil Nadu which provides water supply and sewage treatment to the city of Chennai and its metropolitan region.

Kosasthalaiyar River, also known as Kortalaiyar, is one of the three rivers that flow in the Chennai metropolitan area.

The Climate of Tamil Nadu, India is generally tropical and features fairly hot temperatures over the year except during the monsoon seasons. The city of Chennai lies on the thermal equator, which means Chennai and Tamil Nadu does not have that much temperature variation.

Water scarcity in India is an ongoing water crisis that affects nearly hundreds of million of people each year. In addition to affecting the huge rural and urban population, the water scarcity in India also extensively affects the ecosystem and agriculture. India has only 4% of the world's fresh water resources despite a population of over 1.4 billion people. In addition to the disproportionate availability of freshwater, water scarcity in India also results from drying up of rivers and their reservoirs in the summer months, right before the onset of the monsoons throughout the country. The crisis has especially worsened in the recent years due to climate change which results in delayed monsoons, consequently drying out reservoirs in several regions. Other factors attributed to the shortage of water in India are a lack of proper infrastructure and government oversight and unchecked water pollution.

The coastal city of Chennai has a metropolitan population of 10.6 million as per 2019 census. As the city lacks a perennial water source, catering the water requirements of the population has remained an arduous task. On 18 June 2019, the city's reservoirs ran dry, leaving the city in severe crisis.

Poondi Reservoir or Sathyamoorthy reservoir is the reservoir across Kotralai River in Tiruvallur district of Tamil Nadu state in India. It acts as the important water source for Chennai city which is 60 km away.

This is a list of notable recorded floods that have occurred in India. Floods are the most common natural disaster in India. The heaviest southwest, the Brahmaputra, and other rivers to distend their banks, often flooding surrounding areas.

The 2015 South India floods resulted from heavy rainfall generated by the annual northeast monsoon in November–December 2015. They affected the Coromandel Coast region of the South Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. More than 500 people were killed and over 1.8 million people were displaced. With estimates of damages and losses ranging from nearly ₹200 billion (US$3 billion) to over ₹1 trillion (US$13 billion), the floods were the costliest to have occurred in 2015, and were among the costliest natural disasters of the year.

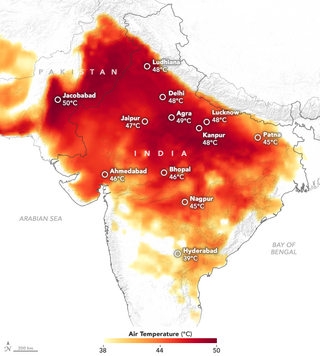

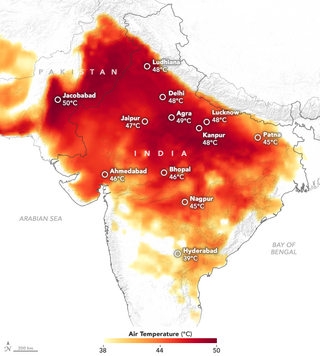

From mid-May to mid-June 2019, the republics of India and Pakistan had a severe heat wave. It was one of the hottest and longest heat waves in the subcontinent since the two countries began recording weather reports. The highest temperatures occurred in Churu, Rajasthan, reaching up to 50.8 °C (123.4 °F), a near record high in India, missing the record of 51.0 °C (123.8 °F) set in 2016 by a fraction of a degree. As of 12 June 2019, 32 days are classified as parts of the heatwave, making it the second longest ever recorded.

Very Severe Cyclonic Storm Nivar was a tropical cyclone which brought severe impacts to portions of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh in late November 2020. The eighth depression and fourth named storm of the 2020 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, Nivar originated from a disturbance in the Intertropical Convergence Zone. The disturbance gradually organized and on 23 November, both the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) and the India Meteorological Department (IMD) reported that a tropical depression had formed. On the next day, both agencies upgraded the system to a tropical storm, with the latter assigning it the name Nivar. Nivar made its landfall over north coastal Tamil Nadu between Puducherry and Chennai close to Marakkanam. Overall, Nivar caused $600 million in damages.

The effects of the 2020 North Indian Ocean cyclone season in India was considered one of the worst in decades, largely due to Super Cyclonic Storm Amphan. Throughout most of the year, a series of cyclones impacted the country, with the worst damage occurring in May, from Cyclone Amphan. The season started with Super Cyclonic Storm Amphan, which affected East India with very severe damages. 98 total people died from the storm. Approximately 1,167 km (725 mi) of power lines of varying voltages, 126,540 transformers, and 448 electrical substations were affected, leaving 3.4 million without power. Damage to the power grid reached ₹3.2 billion. Four people died in Odisha, two from collapsed objects, one due to drowning, and one from head trauma. Across the ten affected districts in Odisha, 4.4 million people were impacted in some way by the cyclone. At least 500 homes were destroyed and a further 15,000 were damaged. Nearly 4,000 livestock, primarily poultry, died. The cyclone was strongest at its northeast section. The next storm was a depression that did not affect India. Then Severe Cyclonic Storm Nisarga hit Maharashtra, with high damages. Nisarga caused 6 deaths and 16 injuries in the state. Over 5,033 ha of land were damaged.

The 2021 South India floods are a series of floods associated with Depression BOB 05 and a low pressure system that caused widespread disruption across the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and the nearby Sri Lanka. The rainfall started on 1 November in Tamil Nadu. The flooding was caused by extremely heavy downpours from BOB 05, killing at least 41 people across India and Sri Lanka.