Related Research Articles

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Different cultures have employed forms of astrology since at least the 2nd millennium BCE, these practices having originated in calendrical systems used to predict seasonal shifts and to interpret celestial cycles as signs of divine communications. Most, if not all, cultures have attached importance to what they observed in the sky, and some—such as the Hindus, Chinese, and the Maya—developed elaborate systems for predicting terrestrial events from celestial observations. Western astrology, one of the oldest astrological systems still in use, can trace its roots to 19th–17th century BCE Mesopotamia, from where it spread to Ancient Greece, Rome, the Islamic world, and eventually Central and Western Europe. Contemporary Western astrology is often associated with systems of horoscopes that purport to explain aspects of a person's personality and predict significant events in their lives based on the positions of celestial objects; the majority of professional astrologers rely on such systems.

Abraham ben Meir Ibn Ezra was one of the most distinguished Jewish biblical commentators and philosophers of the Middle Ages. He was born in Tudela, Taifa of Zaragoza.

Hindu astrology, also called Indian astrology, Jyotisha, Jyotish Shastra, and more recently Vedic astrology, is the traditional Hindu system of astrology. It is one of the six auxiliary disciplines in Hinduism that is connected with the study of the Vedas.

The House of Wisdom, also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, was believed to be a major Abbasid-era public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad. In popular reference, it acted as one of the world's largest public libraries during the Islamic Golden Age, and was founded either as a library for the collections of the fifth Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid in the late 8th century or as a private collection of the second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur to house rare books and collections of poetry in the Arabic and Persian language. During the reign of the seventh Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun, it was turned into a public academy and a library.

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī aṣ-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī, usually called al-Battānī, a name that was in the past Latinized as Albategnius, was an astronomer, astrologer and mathematician, who lived and worked for most of his life at Raqqa, now in Syria. He is considered to be the greatest and most famous of the astronomers of the medieval Islamic world.

Astrological belief in correspondences between celestial observations and terrestrial events have influenced various aspects of human history, including world-views, language and many elements of social culture.

Abu al-Hasan 'Ali ibn Abi al-Said 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Ahmad ibn Yunus ibn Abd al-'Ala al-Sadafi al-Misri was an important Egyptian astronomer and mathematician, whose works are noted for being ahead of their time, having been based on meticulous calculations and attention to detail. He is one of the famous Muslim astronomers who appeared after Al-Battani and Abu al-Wafa' al-Buzjani, and he was perhaps the greatest astronomer of his time. Because of his brilliance, the Fatimids gave him generous gifts and established an observatory for him on Mount Mokattam near Fustat. Al-Aziz Billah ordered him to make astronomical tables, which he completed during the reign of Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, son of Al-Aziz, and called it al-Zij al-Kabir al-Hakimi. The crater Ibn Yunus on the Moon is named after him.

Abu Ma‘shar al-Balkhi, Latinized as Albumasar, was an early Persian Muslim astrologer, thought to be the greatest astrologer of the Abbasid court in Baghdad. While he was not a major innovator, his practical manuals for training astrologers profoundly influenced Muslim intellectual history and, through translations, that of western Europe and Byzantium.

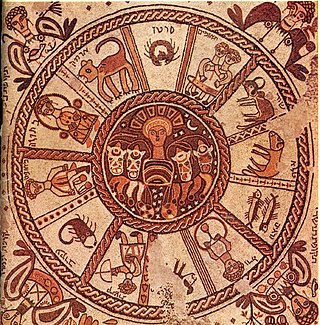

Astrology has been a topic of debate among Jews for over 2000 years. While not a Jewish practice or teaching as such, astrology made its way into Jewish thought, as can be seen in the many references to it in the Talmud. Astrological statements became accepted and worthy of debate and discussion by Torah scholars. Opinions varied: some rabbis rejected the validity of astrology; others accepted its validity but forbid practicing it; still others thought its practice to be meaningful and permitted. In modern times, as science has rejected the validity of astrology, many Jewish thinkers have similarly rejected it; though some continue to defend the pro-astrology views that were common among pre-modern Jews.

Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī, known as Mashallah, was an 8th century Persian Jewish astrologer, astronomer, and mathematician. Originally from Khorasan, he lived in Basra during the reigns of the Abbasid caliphs al-Manṣūr and al-Ma’mūn, and was among those who introduced astrology and astronomy to Baghdad. The bibliographer ibn al-Nadim described Mashallah "as virtuous and in his time a leader in the science of jurisprudence, i.e. the science of judgments of the stars". Mashallah served as a court astrologer for the Abbasid caliphate and wrote works on astrology in Arabic. Some Latin translations survive.

Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Nahawandi, also called al-Nahawandi, was an 8th/9th century Persian astronomer. His name indicates that he was from Nahavand, now in modern Iran.

Medieval Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age, and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle East, Central Asia, Al-Andalus, and North Africa, and later in the Far East and India. It closely parallels the genesis of other Islamic sciences in its assimilation of foreign material and the amalgamation of the disparate elements of that material to create a science with Islamic characteristics. These included Greek, Sassanid, and Indian works in particular, which were translated and built upon.

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia. The numeral system used, sexagesimal, was based on sixty, as opposed to ten in the modern decimal system. This system simplified the calculating and recording of unusually great and small numbers.

The three brothers Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir ; Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir, were Persian scholars who lived and worked in Baghdad. They are collectively known as the Banū Mūsā.

Babylonian astrology was the first known organized system of astrology, arising in the second millennium BC.

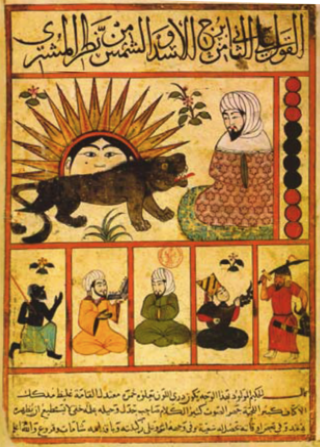

Some medieval Muslims took a keen interest in the study of astrology, partly because they considered the celestial bodies to be essential, partly because the dwellers of desert-regions often travelled at night, and relied upon knowledge of the constellations for guidance in their journeys.

Omar Tiberiades or Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar ibn al-Farrukhān al-Tabari, was a Medieval Persian astrologer and architect from Tabaristan.

Sinhala numerals, are the units of the numeral system, originating from the Indian subcontinent, used in Sinhala language in modern-day Sri Lanka.

Liber de orbe was a Latin translation made in 1130s CE of an Arabic work attributed to the 8th century astrologer Mashallah ibn Athari.

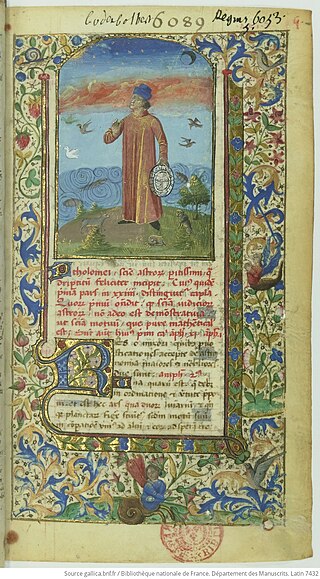

Latin 7432 is a medieval astronomical manuscript preserved as a part of the Latin collection in Bibliothèque nationale de France. This is an outstanding example of a presentation manuscript. It was produced under the supervision of Swiss astrologer and physician Conrad Heingarter for his patron Jean II, Duke of Bourbon in the second half of the 15th century. The content of this manuscript mainly concerns astrology and astronomy. It includes major texts on the astrological subject such as Ptolemy's Quadripartitum, Pseudo-Ptolemy Centiloquium and the works of Mashallah ibn Athari. It also contains Parisian Alfonsine tables complemented by the respective canons composed by John of Saxony. This manuscript is highly illuminated and contains a large number of decorative miniatures and technical diagrams.

References

- 1 2 Benjamin N. Dykes [translator]. Works of Sahl and Masha'allah. Cazimi Press, 2008. Archived 2009-11-14 at the Wayback Machine .

- ↑ The use of zero, essential in practical mathematics, is now familiar in India and is adopted in Baghdad