A prayer wheel, or mani wheel, is a cylindrical wheel for Buddhist recitation. The wheel is installed on a spindle made from metal, wood, stone, leather, or coarse cotton. Prayer wheels are common in Tibet and areas where Tibetan culture is predominant.

Tibetan Buddhism is a form of Buddhism practiced in China, Bhutan and Mongolia. It also has a sizable number of adherents in the areas surrounding the Himalayas, including the Indian regions of Ladakh, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh, as well as in Nepal. Smaller groups of practitioners can be found in Central Asia, some regions of China like Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and some regions of Russia, such as Tuva, Buryatia, and Kalmykia.

Vajrayāna, also known as Mantrayāna, Mantranāya, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, is a Buddhist tradition of tantric practice that developed in Medieval India and spread to Tibet, Nepal, other Himalayan states, East Asia, parts of Southeast Asia and Mongolia.

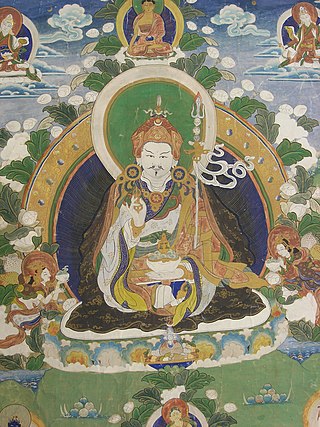

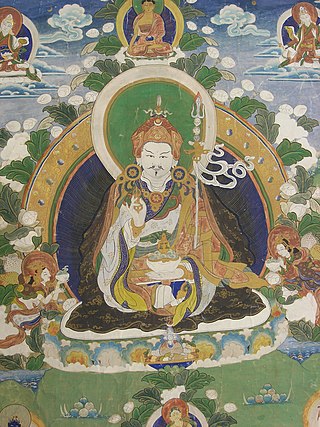

Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche and the Lotus from Oḍḍiyāna, was a tantric Buddhist Vajra master from medieval India who taught Vajrayana in Tibet. According to some early Tibetan sources like the Testament of Ba, he came to Tibet in the 8th century and helped construct Samye Monastery, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. However, little more is known about the actual historical figure other than his ties to Vajrayana and Indian Buddhism.

The Gelug is the newest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. It was founded by Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), a Tibetan philosopher, tantric yogi and lama and further expanded and developed by his disciples.

The Kadam school of Tibetan Buddhism was an 11th century Buddhist tradition founded by the great Bengali master Atiśa (982–1054) and his students like Dromtön (1005–1064), a Tibetan Buddhist lay master. The Kadampa stressed compassion, pure discipline and study.

The vast majority of surviving Tibetan art created before the mid-20th century is religious, with the main forms being thangka, paintings on cloth, mostly in a technique described as gouache or distemper, Tibetan Buddhist wall paintings, and small statues in bronze, or large ones in clay, stucco or wood. They were commissioned by religious establishments or by pious individuals for use within the practice of Tibetan Buddhism and were manufactured in large workshops by monks and lay artists, who are mostly unknown. Various types of religious objects, such as the phurba or ritual dagger, are finely made and lavishly decorated. Secular objects, in particular jewellery and textiles, were also made, with Chinese influences strong in the latter.

The schools of Buddhism are the various institutional and doctrinal divisions of Buddhism which are the teachings off buddhist texts. The schools of Buddhism have existed from ancient times up to the present. The classification and nature of various doctrinal, philosophical or cultural facets of the schools of Buddhism is vague and has been interpreted in many different ways, often due to the sheer number of different sects, subsects, movements, etc. that have made up or currently make up the whole of Buddhist traditions. The sectarian and conceptual divisions of Buddhist thought are part of the modern framework of Buddhist studies, as well as comparative religion in Asia. Some factors in Buddhism appear to be consistent, such as the afterlife. Which differs on the version of Buddhism.

Buddhist music is music created for or inspired by Buddhism and includes numerous ritual and non-ritual musical forms. As a Buddhist art form, music has been used by Buddhists since the time of early Buddhism, as attested by artistic depictions in Indian sites like Sanchi. While certain early Buddhist sources contain negative attitudes to music, Mahayana sources tend to be much more positive to music, seeing it as a suitable offering to the Buddhas and as a skillful means to bring sentient beings to Buddhism.

A lineage in Buddhism is a line of transmission of the Buddhist teaching that is "theoretically traced back to the Buddha himself." The acknowledgement of the transmission can be oral, or certified in documents. Several branches of Buddhism, including Chan and Tibetan Buddhism maintain records of their historical teachers. These records serve as a validation for the living exponents of the tradition.

A thangka is a Tibetan Buddhist painting on cotton, silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala. Thangkas are traditionally kept unframed and rolled up when not on display, mounted on a textile backing somewhat in the style of Chinese scroll paintings, with a further silk cover on the front. So treated, thangkas can last a long time, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places where moisture will not affect the quality of the silk. Most thangkas are relatively small, comparable in size to a Western half-length portrait, but some are extremely large, several metres in each dimension; these were designed to be displayed, typically for very brief periods on a monastery wall, as part of religious festivals. Most thangkas were intended for personal meditation or instruction of monastic students. They often have elaborate compositions including many very small figures. A central deity is often surrounded by other identified figures in a symmetrical composition. Narrative scenes are less common, but do appear.

A vajrācārya is a Vajrayana Buddhist master, guru or priest. It is a general term for a tantric master in Vajrayana Buddhist traditions, including Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Bhutanese Buddhism, Newar Buddhism.

The Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) was founded in 1975 by Gelugpa Lamas Thubten Yeshe and Thubten Zopa Rinpoche, who began teaching Tibetan Buddhism to Western students in Nepal. The FPMT has grown to encompass over 138 dharma centers, projects, and services in 34 countries. Lama Yeshe led the organization until his death in 1984, followed by Lama Zopa until his death in 2023. The FPMT is now without a spiritual director; meetings on the organization's structure and future are planned.

Mahākāla is a deity common to Hinduism and Buddhism.

Women in Buddhism is a topic that can be approached from varied perspectives including those of theology, history, anthropology, and feminism. Topical interests include the theological status of women, the treatment of women in Buddhist societies at home and in public, the history of women in Buddhism, and a comparison of the experiences of women across different forms of Buddhism. As in other religions, the experiences of Buddhist women have varied considerably.

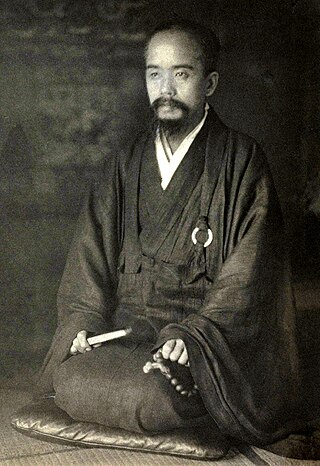

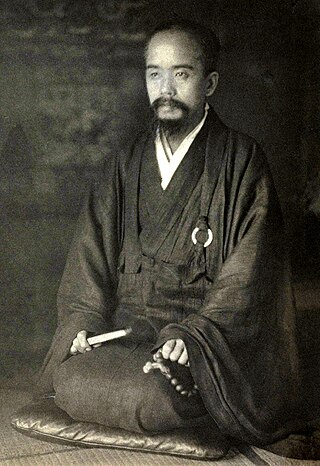

Ekai Kawaguchi was a Japanese Buddhist monk who was famed for his four journeys to Nepal and two to Tibet. He was the first recorded Japanese citizen to travel to either country.

Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism or Esoteric Buddhism in Maritime Southeast Asia refers to the traditions of Esoteric Buddhism found in Maritime Southeast Asia which emerged in the 7th century along the maritime trade routes and port cities of the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra as well as in Malaysia. These esoteric forms were spread by pilgrims and Tantric masters who received royal patronage from royal dynasties like the Sailendras and the Srivijaya. This tradition was also linked by the maritime trade routes with Indian Vajrayana, Tantric Buddhism in Sinhala, Cham and Khmer lands and in China and Japan, to the extent that it is hard to separate them completely and it is better to speak of a complex of "Esoteric Buddhism of Mediaeval Maritime Asia." Many key Indian port cities saw the growth of Esoteric Buddhism, a tradition which coexisted alongside Shaivism.

Dampa Sangye was a Buddhist mahasiddha of the Indian Tantra movement who transmitted many teachings based on both Sutrayana and Tantrayana to Buddhist practitioners in Tibet in the late 11th century. He travelled to Tibet more than five times. On his third trip from India to Tibet he met Machig Labdrön. Dampa Sangye appears in many of the lineages of Chöd and so in Tibet he is known as the Father of Chod, however perhaps his best known teaching is "the Pacification". This teaching became an element of the Mahamudra Chöd lineages founded by Machig Labdrön.

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism refers to traditions of Tantra and Esoteric Buddhism that have flourished among the Chinese people. The Tantric masters Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, established the Esoteric Buddhist Zhenyan tradition from 716 to 720 during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. It employed mandalas, mantras, mudras, abhiṣekas, and deity yoga. The Zhenyan tradition was transported to Japan as Shingon Buddhism by Kūkai as well as influencing Korean Buddhism and Vietnamese Buddhism. The Song dynasty (960–1279) saw a second diffusion of Esoteric texts. Esoteric Buddhist practices continued to have an influence into the late imperial period and Tibetan Buddhism was also influential during the Yuan dynasty period and beyond. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) through to the modern period, esoteric practices and teachings became absorbed and merged with the other Chinese Buddhist traditions to a large extent.