Related Research Articles

In materials science, superplasticity is a state in which solid crystalline material is deformed well beyond its usual breaking point, usually over about 400% during tensile deformation. Such a state is usually achieved at high homologous temperature. Examples of superplastic materials are some fine-grained metals and ceramics. Other non-crystalline materials (amorphous) such as silica glass and polymers also deform similarly, but are not called superplastic, because they are not crystalline; rather, their deformation is often described as Newtonian fluid. Superplastically deformed material gets thinner in a very uniform manner, rather than forming a "neck" that leads to fracture. Also, the formation of microvoids, which is another cause of early fracture, is inhibited. Superplasticity must not be confused with superelasticity.

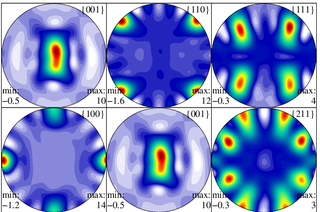

In physical chemistry and materials science, texture is the distribution of crystallographic orientations of a polycrystalline sample. A sample in which these orientations are fully random is said to have no distinct texture. If the crystallographic orientations are not random, but have some preferred orientation, then the sample has a weak, moderate or strong texture. The degree is dependent on the percentage of crystals having the preferred orientation.

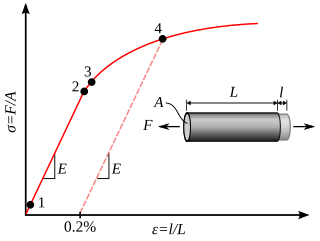

Work hardening, also known as strain hardening, is the process by which a material's load-bearing capacity (strength) increases during plastic (permanent) deformation. This characteristic is what sets ductile materials apart from brittle materials. Work hardening may be desirable, undesirable, or inconsequential, depending on the application.

A superalloy, or high-performance alloy, is an alloy with the ability to operate at a high fraction of its melting point. Key characteristics of a superalloy include mechanical strength, thermal creep deformation resistance, surface stability, and corrosion and oxidation resistance.

Zirconium alloys are solid solutions of zirconium or other metals, a common subgroup having the trade mark Zircaloy. Zirconium has very low absorption cross-section of thermal neutrons, high hardness, ductility and corrosion resistance. One of the main uses of zirconium alloys is in nuclear technology, as cladding of fuel rods in nuclear reactors, especially water reactors. A typical composition of nuclear-grade zirconium alloys is more than 95 weight percent zirconium and less than 2% of tin, niobium, iron, chromium, nickel and other metals, which are added to improve mechanical properties and corrosion resistance.

In materials science and engineering, the yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning of plastic behavior. Below the yield point, a material will deform elastically and will return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible and is known as plastic deformation.

A shear band is a narrow zone of intense shearing strain, usually of plastic nature, developing during severe deformation of ductile materials. As an example, a soil specimen is shown in Fig. 1, after an axialsymmetric compression test. Initially the sample was cylindrical in shape and, since symmetry was tried to be preserved during the test, the cylindrical shape was maintained for a while during the test and the deformation was homogeneous, but at extreme loading two X-shaped shear bands had formed and the subsequent deformation was strongly localized.

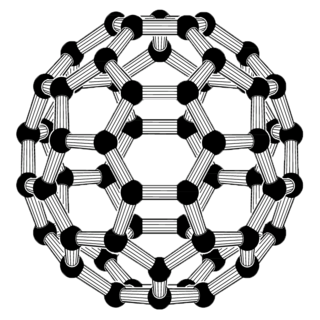

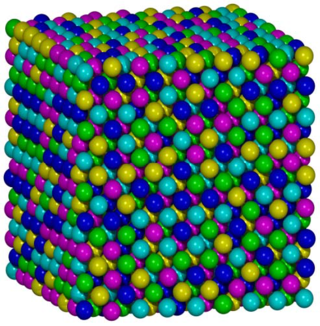

A nanocrystalline (NC) material is a polycrystalline material with a crystallite size of only a few nanometers. These materials fill the gap between amorphous materials without any long range order and conventional coarse-grained materials. Definitions vary, but nanocrystalline material is commonly defined as a crystallite (grain) size below 100 nm. Grain sizes from 100 to 500 nm are typically considered "ultrafine" grains.

A cryogenic treatment is the process of treating workpieces to cryogenic temperatures in order to remove residual stresses and improve wear resistance in steels and other metal alloys, such as aluminum. In addition to seeking enhanced stress relief and stabilization, or wear resistance, cryogenic treatment is also sought for its ability to improve corrosion resistance by precipitating micro-fine eta carbides, which can be measured before and after in a part using a quantimet.

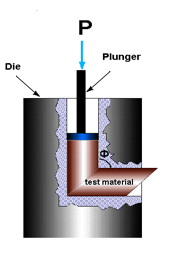

Equal channel angular extrusion (ECAE) called also equal channel angular pressing (ECAP) is one technique from the Severe Plastic Deformation (SPD) group, aimed at producing Ultra Fine Grained (UFG) material. The method was developed in the Soviet Union in 1973 by Segal. However, the dates are not always consistent. In industrial metalworking, it is an extrusion process, The technique is able to refine the microstructure of metals and alloys, thereby improving their strength according to the Hall-Petch relationship. This process improves not only the strength but also other properties such as corrosion and wear resistance of alloys and compounds.

Methods have been devised to modify the yield strength, ductility, and toughness of both crystalline and amorphous materials. These strengthening mechanisms give engineers the ability to tailor the mechanical properties of materials to suit a variety of different applications. For example, the favorable properties of steel result from interstitial incorporation of carbon into the iron lattice. Brass, a binary alloy of copper and zinc, has superior mechanical properties compared to its constituent metals due to solution strengthening. Work hardening has also been used for centuries by blacksmiths to introduce dislocations into materials, increasing their yield strengths.

In materials science, grain-boundary strengthening is a method of strengthening materials by changing their average crystallite (grain) size. It is based on the observation that grain boundaries are insurmountable borders for dislocations and that the number of dislocations within a grain has an effect on how stress builds up in the adjacent grain, which will eventually activate dislocation sources and thus enabling deformation in the neighbouring grain as well. By changing grain size, one can influence the number of dislocations piled up at the grain boundary and yield strength. For example, heat treatment after plastic deformation and changing the rate of solidification are ways to alter grain size.

Mechanical alloying (MA) is a solid-state and powder processing technique involving repeated cold welding, fracturing, and re-welding of blended powder particles in a high-energy ball mill to produce a homogeneous material. Originally developed to produce oxide-dispersion strengthened (ODS) nickel- and iron-base superalloys for applications in the aerospace industry, MA has now been shown to be capable of synthesizing a variety of equilibrium and non-equilibrium alloy phases starting from blended elemental or pre-alloyed powders. The non-equilibrium phases synthesized include supersaturated solid solutions, metastable crystalline and quasicrystalline phases, nanostructures, and amorphous alloys.The method is sometimes is classified as a surface severe platic deformation method to achieve nanomaterials.

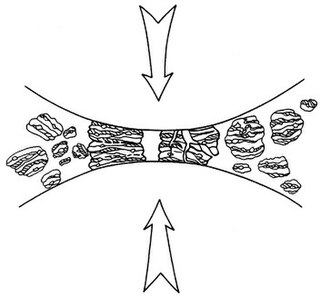

Severe plastic deformation (SPD) is a generic term describing a group of metalworking techniques involving very large strains typically involving a complex stress state or high shear, resulting in a high defect density and equiaxed "ultrafine" grain (UFG) size or nanocrystalline (NC) structure.

High-entropy alloys (HEAs) are alloys that are formed by mixing equal or relatively large proportions of (usually) five or more elements. Prior to the synthesis of these substances, typical metal alloys comprised one or two major components with smaller amounts of other elements. For example, additional elements can be added to iron to improve its properties, thereby creating an iron-based alloy, but typically in fairly low proportions, such as the proportions of carbon, manganese, and others in various steels. Hence, high-entropy alloys are a novel class of materials. The term "high-entropy alloys" was coined by Taiwanese scientist Jien-Wei Yeh because the entropy increase of mixing is substantially higher when there is a larger number of elements in the mix, and their proportions are more nearly equal. Some alternative names, such as multi-component alloys, compositionally complex alloys and multi-principal-element alloys are also suggested by other researchers.

This glossary of structural engineering terms pertains specifically to structural engineering and its sub-disciplines. Please see glossary of engineering for a broad overview of the major concepts of engineering.

In materials science, toughening refers to the process of making a material more resistant to the propagation of cracks. When a crack propagates, the associated irreversible work in different materials classes is different. Thus, the most effective toughening mechanisms differ among different materials classes. The crack tip plasticity is important in toughening of metals and long-chain polymers. Ceramics have limited crack tip plasticity and primarily rely on different toughening mechanisms.

Friction extrusion is a thermo-mechanical process that can be used to form fully consolidated wire, rods, tubes, or other non-circular metal shapes directly from a variety of precursor charges including metal powder, flake, machining waste or solid billet. The process imparts unique, and potentially, highly desirable microstructures to the resulting products. Friction extrusion was invented at The Welding Institute in the UK and patented in 1991. It was originally intended primarily as a method for production of homogeneous microstructures and particle distributions in metal matrix composite materials.

Electroplasticity, describes the enhanced plastic behavior of a solid material under the application of an electric field. This electric field could be internal, resulting in current flow in conducting materials, or external. The effect of electric field on mechanical properties ranges from simply enhancing existing plasticity, such as reducing the flow stress in already ductile metals, to promoting plasticity in otherwise brittle ceramics. The exact mechanisms that control electroplasticity vary based on the material and the exact conditions. Enhancing the plasticity of materials is of great practical interest as plastic deformation provides an efficient way of transforming raw materials into final products. The use of electroplasticity to improve processing of materials is known as electrically assisted manufacturing.

Terence G. Langdon is a scientist and an academic. He is a Professor of Materials Science at the University of Southampton, and a Professor of Engineering Emeritus at the University of Southern California.

References

- ↑ Edalati, K.; Bachmaier, A.; Beloshenko, V.A.; Beygelzimer, Y.; Blank, V.D.; Botta, W.J.; Bryła, K.; Čížek, J.; Divinski, S.; Enikeev, N.A.; Estrin, Y.; Faraji, G.; Figueiredo, R.B.; Fuji, M.; Furuta, T.; Grosdidier, T.; Gubicza, J.; Hohenwarter, A.; Horita, Z.; Huot, J.; Ikoma, Y.; Janeček, M.; Kawasaki, M.; Krǎl, P.; Kuramoto, S.; Langdon, T.G.; Leiva, D.R.; Levitas, V.I.; Mazilkin, A.; Mito, M.; Miyamoto, H.; Nishizaki, T.; Pippan, R.; Popov, V.V.; Popova, E.N.; Purcek, G.; Renk, O.; Révész, A.; Sauvage, X.; Sklenicka, V.; Skrotzki, W.; Straumal, B.B.; Suwas, S.; Toth, L.S.; Tsuji, N.; Valiev, R.Z.; Wilde, G.; Zehetbauer, M.J.; Zhu, X. (April 2022). "Nanomaterials by severe plastic deformation: review of historical developments and recent advances". Materials Research Letters. 10 (4): 163–256. doi: 10.1080/21663831.2022.2029779 . S2CID 246959065.

- ↑ Saito, Y; Utsunomiya, H; Tsuji, N; Sakai, T (1999). "Novel Ultra-High Straining Process for Bulk Materials - Development of the Accumulative Roll-Bonding (ARB)". Acta Materialia. 47 (2): 579–583. doi:10.1016/s1359-6454(98)00365-6.

- ↑ Tsuji, N.; Saito, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Minamino, Y. (2003). "ARB (Accumulative Roll-Bonding) and other new Techniques to Produce Bulk Ultrafine Grained Materials". Advanced Engineering Materials. 5 (5): 338. doi:10.1002/adem.200310077.

- ↑ Karlik; Slamova; Homola (2004). "Accumulative roll-bonding: first experience with a twin-roll cast AA8006 alloy". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 378 (1–2): 322–325. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2003.10.082.