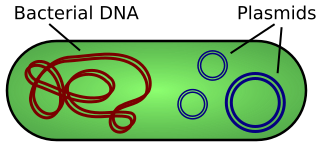

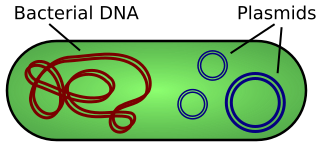

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; however, plasmids are sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotic organisms. In nature, plasmids often carry genes that benefit the survival of the organism and confer selective advantage such as antibiotic resistance. While chromosomes are large and contain all the essential genetic information for living under normal conditions, plasmids are usually very small and contain only additional genes that may be useful in certain situations or conditions. Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms. In the laboratory, plasmids may be introduced into a cell via transformation. Synthetic plasmids are available for procurement over the internet.

Antisense RNA (asRNA), also referred to as antisense transcript, natural antisense transcript (NAT) or antisense oligonucleotide, is a single stranded RNA that is complementary to a protein coding messenger RNA (mRNA) with which it hybridizes, and thereby blocks its translation into protein. The asRNAs have been found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and can be classified into short and long non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). The primary function of asRNA is regulating gene expression. asRNAs may also be produced synthetically and have found wide spread use as research tools for gene knockdown. They may also have therapeutic applications.

P1 is a temperate bacteriophage that infects Escherichia coli and some other bacteria. When undergoing a lysogenic cycle the phage genome exists as a plasmid in the bacterium unlike other phages that integrate into the host DNA. P1 has an icosahedral head containing the DNA attached to a contractile tail with six tail fibers. The P1 phage has gained research interest because it can be used to transfer DNA from one bacterial cell to another in a process known as transduction. As it replicates during its lytic cycle it captures fragments of the host chromosome. If the resulting viral particles are used to infect a different host the captured DNA fragments can be integrated into the new host's genome. This method of in vivo genetic engineering was widely used for many years and is still used today, though to a lesser extent. P1 can also be used to create the P1-derived artificial chromosome cloning vector which can carry relatively large fragments of DNA. P1 encodes a site-specific recombinase, Cre, that is widely used to carry out cell-specific or time-specific DNA recombination by flanking the target DNA with loxP sites.

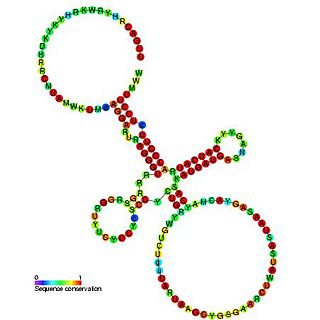

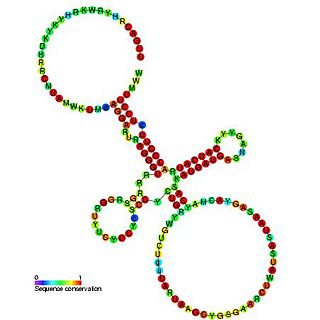

Sib RNA refers to a group of related non-coding RNA. They were originally named QUAD RNA after they were discovered as four repeat elements in Escherichia coli intergenic regions. The family was later renamed Sib when it was discovered that the number of repeats is variable in other species and in other E. coli strains.

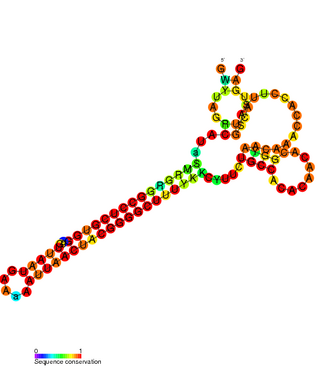

The hok/sok system is a postsegregational killing mechanism employed by the R1 plasmid in Escherichia coli. It was the first type I toxin-antitoxin pair to be identified through characterisation of a plasmid-stabilising locus. It is a type I system because the toxin is neutralised by a complementary RNA, rather than a partnered protein.

In a screen of the Bacillus subtilis genome for genes encoding ncRNAs, Saito et al. focused on 123 intergenic regions (IGRs) over 500 base pairs in length, the authors analyzed expression from these regions. Seven IGRs termed bsrC, bsrD, bsrE, bsrF, bsrG, bsrH and bsrI expressed RNAs smaller than 380 nt. All the small RNAs except BsrD RNA were expressed in transformed Escherichia coli cells harboring a plasmid with PCR-amplified IGRs of B. subtilis, indicating that their own promoters independently express small RNAs. Under non-stressed condition, depletion of the genes for the small RNAs did not affect growth. Although their functions are unknown, gene expression profiles at several time points showed that most of the genes except for bsrD were expressed during the vegetative phase, but undetectable during the stationary phase. Mapping the 5' ends of the 6 small RNAs revealed that the genes for BsrE, BsrF, BsrG, BsrH, and BsrI RNAs are preceded by a recognition site for RNA polymerase sigma factor σA.

PtaRNA1 is a family of non-coding RNAs. Homologs of PtaRNA1 can be found in the bacterial families, Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. In all cases the PtaRNA1 is located anti-sense to a short protein-coding gene. In Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, this gene is annotated as XCV2162 and is included in the plasmid toxin family of proteins.

The TisB-IstR toxin-antitoxin system is the first known toxin-antitoxin system which is induced by the SOS response in response to DNA damage.

A toxin-antitoxin system consists of a "toxin" and a corresponding "antitoxin", usually encoded by closely linked genes. The toxin is usually a protein while the antitoxin can be a protein or an RNA. Toxin-antitoxin systems are widely distributed in prokaryotes, and organisms often have them in multiple copies. When these systems are contained on plasmids – transferable genetic elements – they ensure that only the daughter cells that inherit the plasmid survive after cell division. If the plasmid is absent in a daughter cell, the unstable antitoxin is degraded and the stable toxic protein kills the new cell; this is known as 'post-segregational killing' (PSK).

RdlD RNA is a family of small non-coding RNAs which repress the protein LdrD in a type I toxin-antitoxin system. It was discovered in Escherichia coli strain K-12 in a long direct repeat (LDR) named LDR-D. This locus encodes two products: a 35 amino acid peptide toxin (ldrD) and a 60 nucleotide RNA antitoxin. The 374nt toxin mRNA has a half-life of around 30 minutes while rdlD RNA has a half-life of only 2 minutes. This is in keeping with other type I toxin-antitoxin systems.

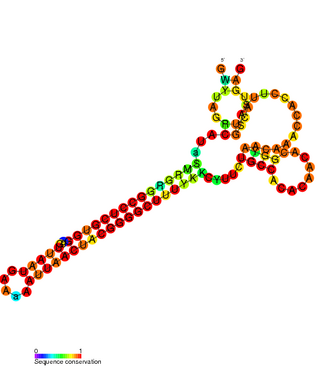

The SymE-SymR toxin-antitoxin system consists of a small symbiotic endonuclease toxin, SymE, and a non-coding RNA symbiotic RNA antitoxin, SymR, which inhibits SymE translation. SymE-SymR is a type I toxin-antitoxin system, and is under regulation by the antitoxin, SymR. The SymE-SymR complex is believed to play an important role in recycling damaged RNA and DNA. The relationship and corresponding structures of SymE and SymR provide insight into the mechanism of toxicity and overall role in prokaryotic systems.

The FlmA-FlmB toxin-antitoxin system consists of FlmB RNA, a family of non-coding RNAs and the protein toxin FlmA. The FlmB RNA transcript is 100 nucleotides in length and is homologous to sok RNA from the hok/sok system and fulfills the identical function as a post-segregational killing (PSK) mechanism.

The TxpA/RatA toxin-antitoxin system was first identified in Bacillus subtilis. It consists of a non-coding 222nt sRNA called RatA and a protein toxin named TxpA.

The par stability determinant is a 400 bp locus of the pAD1 plasmid which encodes a type I toxin-antitoxin system in Enterococcus faecalis. It was the first such plasmid addiction module to be found in gram-positive bacteria.

VapBC is the largest family of type II toxin-antitoxin system genetic loci in prokaryotes. VapBC operons consist of two genes: VapC encodes a toxic PilT N-terminus (PIN) domain, and VapB encodes a matching antitoxin. The toxins in this family are thought to perform RNA cleavage, which is inhibited by the co-expression of the antitoxin, in a manner analogous to a poison and antidote.

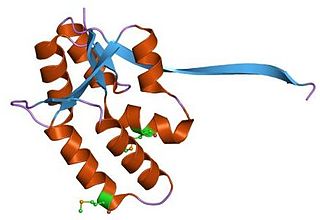

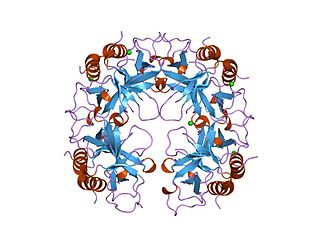

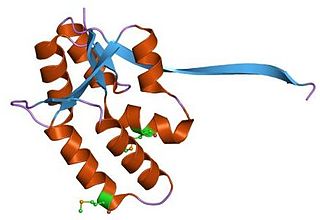

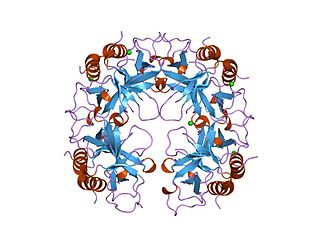

In molecular biology, the Fic/DOC protein family is a family of proteins which catalyzes the post-translational modification of proteins using phosphate-containing compound as a substrate. Fic domain proteins typically use ATP as a co-factor, but in some cases GTP or UTP is used. Post-translational modification performed by Fic domains is usually NMPylation, however they also catalyze phosphorylation and phosphocholine transfer. This family contains a central conserved motif HPFX[D/E]GNGR in most members and it carries the invariant catalytic histidine. Fic domain was found in bacteria, eukaryotes and archaea and can be found organized in almost hundred different multi-domain assemblies.

The SrnB-SrnC toxin-antitoxin system of the F plasmid is homologous to the hok/sok system of R1. Like the hok/sok system, it performs a post-segregational killing function, ensuring that all surviving daughter cells inherit the F plasmid. The system consists of srnB' mRNA, which is relatively stable and codes for the toxic protein SrnB, srnB mRNA, a regulatory element and srnC mRNA, an antitoxin with complementarity to srnB.

The CcdA/CcdB Type II Toxin-antitoxin system is one example of the bacterial toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems that encode two proteins, one a potent inhibitor of cell proliferation (toxin) and the other its specific antidote (antitoxin). These systems preferentially guarantee growth of plasmid-carrying daughter cells in a bacterial population by killing newborn bacteria that have not inherited a plasmid copy at cell division.

In cellular biology, the plasmid copy number is the number of copies of a given plasmid in a cell. To ensure survival and thus the continued propagation of the plasmid, they must regulate their copy number. If a plasmid has too high of a copy number, they may excessively burden their host by occupying too much cellular machinery and using too much energy. On the other hand, too low of a copy number may result in the plasmid not being present in all of their host's progeny. Plasmids may be either low, medium or high copy number plasmids; the regulation mechanisms between low and medium copy number plasmids are different. Low copy plasmids require either a partitioning system or a toxin-antitoxin pair such as CcdA/CcdB to ensure that each daughter receives the plasmid. For example, the F plasmid, which is the origin of BACs is a single copy plasmid with a partitioning system encoded in an operon right next to the plasmid origin. The partitioning system interacts with the septation apparatus to ensure that each daughter receives a copy of the plasmid. Many biotechnology applications utilize mutated plasmids that replicate to high copy number. For example, pBR322 is a medium copy number plasmid from which several high copy number cloning vectors have been derived by mutagenesis, such as the well known pUC series. This delivers the convenience of high plasmid DNA yields but the additional burden of the high copy number restricts the plasmid size. Larger high copy plasmids (>30kb) are disfavoured and also prone to size reduction through deletional mutagenesis.

cII or transcriptional activator II is a DNA-binding protein and important transcription factor in the life cycle of lambda phage. It is encoded in the lambda phage genome by the 291 base pair cII gene. cII plays a key role in determining whether the bacteriophage will incorporate its genome into its host and lie dormant (lysogeny), or replicate and kill the host (lysis).