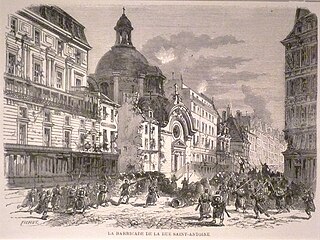

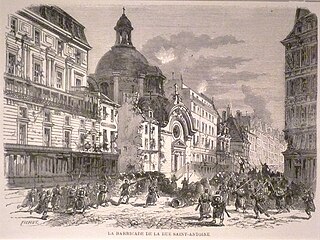

The Paris Commune was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended Paris, and working-class radicalism grew among its soldiers. Following the establishment of the French Third Republic in September 1870 and the complete defeat of the French Army by the Germans by March 1871, soldiers of the National Guard seized control of the city on 18 March. The Communards killed two French army generals and refused to accept the authority of the Third Republic; instead, the radicals set about establishing their own independent government.

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

The Communards were members and supporters of the short-lived 1871 Paris Commune formed in the wake of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.

In politics, a red flag is predominantly a symbol of left-wing ideologies, including socialism, communism, anarchism, and the labour movement. The originally empty or plain red flag has been associated with left-wing politics since the French Revolution (1789–1799). The red flag and red as a political colour are the oldest symbols of socialism.

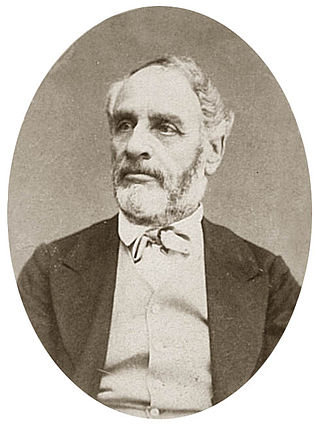

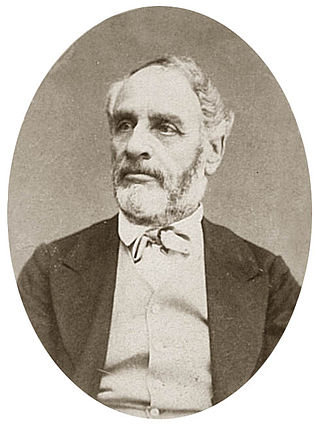

Louis Charles Delescluze was a French revolutionary leader, journalist, and military commander of the Paris Commune.

The Hôtel de Ville is the city hall of Paris, France, standing on the Place de l'Hôtel-de-Ville – Esplanade de la Libération in the 4th arrondissement. The south wing was originally constructed by Francis I beginning in 1535 until 1551. The north wing was built by Henry IV and Louis XIII between 1605 and 1628. It was burned by the Paris Commune, along with all the city archives that it contained, during the Semaine Sanglante, the Commune's final days, in May 1871. The outside was rebuilt following the original design, but larger, between 1874 and 1882, while the inside was considerably modified. It has been the headquarters of the municipality of Paris since 1357. It serves multiple functions, housing the local government council, since 1977 the Mayors of Paris and their cabinets, and also serves as a venue for large receptions. It was designated a monument historique by the French government in 1975.

The Government of National Defense was the first government of the Third Republic of France from 4 September 1870 to 13 February 1871 during the Franco-Prussian War. It was formed after the proclamation of the Republic in Paris on 4 September, which in turn followed the surrender and capture of Emperor Napoleon III by the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan. The government, headed by General Louis Jules Trochu, was under Prussian siege in Paris. Breakouts were attempted twice, but met with disaster and rising dissatisfaction of the public. In late January the government, having further enraged the population of Paris by crushing a revolutionary uprising, surrendered to the Prussians. Two weeks later, it was replaced by the new government of Adolphe Thiers, which soon passed a variety of financial laws in an attempt to pay reparations and thus oblige the Prussians to leave France, leading to the outbreak of revolutions in French cities, and the ultimate creation of the Paris Commune.

Leo Fränkel 25 February 1844, Altofen-Neustift, Austro-Hungarian Empire – 29 March 1896, Paris) was a socialist revolutionary, labour leader of Jewish descent. In France where he participated in the Paris Commune of 1871 as a member of the International and after his return to Paris in 1889, he was known as Léo Frankel.

Théophile Charles Gilles Ferré was one of the members of the Paris Commune. He authorized the executions of Georges Darboy, the archbishop of Paris, and five other hostages, on 24 May 1871. He was captured by the army, tried by a military court, and was shot at Satory. He was the first of twenty-five Commune members to be executed for their role in the Paris Commune.

Marie Édouard Vaillant was a French politician.

Events from the year 1871 in France.

The New Babylon is a 1929 silent historical drama film written and directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg. The film deals with the 1871 Paris Commune and the events leading to it, and follows the encounter and tragic fate of two lovers separated by the barricades of the Commune.

The Mokrani Revolt was the most important local uprising against France in Algeria since the conquest in 1830.

This chronology of the Paris Commune lists major events that occurred during and surrounding the Paris Commune, a revolutionary government that controlled Paris between March and May 1871.

The Lyon Commune was a short-lived revolutionary movement in Lyon, France, in 1870–1871. Republicans and activists from several components of the far-left of the time seized power in Lyon and established an autonomous government. The commune organized elections, but dissolved after the restoration of a republican "normality", which frustrated the most radical elements, who hoped for a different revolution. Radicals twice tried to regain power, without success.

The semaine sanglante was a weeklong battle in Paris from 21 to 28 May 1871, during which the French Army recaptured the city from the Paris Commune. This was the final battle of the Paris Commune.

The Commune Council, simply known as the Commune, was the government during the 72-day Paris Commune in 1871. Following elections on 26 March, the municipal council adopted the formal name Paris Commune in its first session, implying a more revolutionary intent. The council declared itself and its name on 28 March at the Hôtel de Ville as a celebratory event. Their first proclamation followed the next day, reminding citizens of their autonomy and warning of civil war. The Commune was supported by the vast majority of Parisians. The Central Committee of the National Guard recognized and relinquished power to the Commune, but continued to organize as the "guardian of the revolution". The two groups exercised a de facto dual sovereignty.

On 1 March 1871 the Imperial German Army paraded through Paris to mark their victory in the Franco-Prussian War. The city had been under siege by Prussian forces since September 1870, with Prussia being unified into the German Empire on 18 January 1871. The Armistice of Versailles of 28 January ended hostilities, but the city remained in French hands. Preliminary peace terms were agreed in the 26 February Treaty of Versailles, which allowed 30,000 German troops to occupy Paris from 1 March until the treaty was ratified.

On January 22, 1871, a contingent of France's National Guard marched on Paris's City Hall. The group opposed the armistice that was being drafted, believing that the French government had sabotaged their military. Demonstrators released Gustave Flourens and marched on the City Hall, including 150 guardsmen. But unlike the larger City Hall uprising three months earlier, Breton Mobile Guards defended the building. Five died, and 18 were wounded. Though the event had been smaller than the October uprising, the January insurrection irreconcilably split Paris's factions and presaged the coming civil war.

The Federated Legion of Women was an armed unit composed of women active during the Paris Commune in May 1871. It was founded in the 12th arrondissement, with the intended mission of hunting down deserters. The legion had uniforms, parades, and a standard-bearer, and was led by two officers, Colonel Adélaïde Valentin and Captain Louise Neckbecker. There were an estimated 20-100 members, most from working-class backgrounds. They held and attended meetings in Parisian political clubs, where they incited citizens to take up arms. After the defeat of the Commune, arrested members were given heavy sentences, including forced labour and deportation.