Beadwork is the art or craft of attaching beads to one another by stringing them onto a thread or thin wire with a sewing or beading needle or sewing them to cloth. Beads are produced in a diverse range of materials, shapes, and sizes, and vary by the kind of art produced. Most often, beadwork is a form of personal adornment, but it also commonly makes up other artworks.

Zulu people are a native people of Southern Africa of the Nguni. The Zulu people are the largest ethnic group and nation in South Africa, with an estimated 13.56 million people, living mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

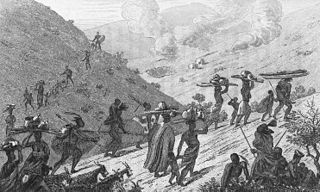

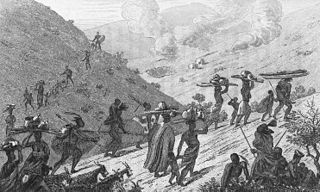

The Mfecane, also known by the Sesotho names Difaqane or Lifaqane, is a historical period of heightened military conflict and migration associated with state formation and expansion in Southern Africa. The exact range of dates that comprise the Mfecane varies between sources. At its broadest, the period lasted from the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century, but scholars often focus on an intensive period from the 1810s to the 1840s. The concept first emerged in the 1830s and blamed the disruption on the actions of Shaka Zulu, who was alleged to have waged near-genocidal wars that depopulated the land and sparked a chain reaction of violence as fleeing groups sought to conquer new lands. Since the latter half of the 20th century, this interpretation has fallen out of favor among scholars due to a lack of historical evidence.

Kraal is an Afrikaans and Dutch word, also used in South African English, for an enclosure for cattle or other livestock, located within a Southern African settlement or village surrounded by a fence of thorn-bush branches, a palisade, mud wall, or other fencing, roughly circular in form. It is similar to a boma in eastern or central Africa.

The Damara, plural Damaran are an ethnic group who make up 8.5% of Namibia's population. They speak the Khoekhoe language and the majority live in the northwestern regions of Namibia, however they are also found widely across the rest of the country.

African clothing is the traditional clothing worn by the people of Africa.

Unkulunkulu (/uɲɠulun'ɠulu/), often formatted as uNkulunkulu, is a mythical ancestor, mythical predecessor group, or Supreme Creator in the language of the Zulu, Ndebele and Swati people. Originally a "first ancestor" figure, Unkulunkulu morphed into a creator god figure with the spread of Christianity.

Inyathi is a village located in the Bubi District of Matabeleland North, Zimbabwe that grew from colonization by missionaries in the late 19th century. The Mission itself sits upon around 2,729 hectares of land. Inyathi is about 100 kilometres (62 mi) from Bulawayo and has a number of gold mines that have inspired both corporate and illegal mining.

Ndebele house painting is a style of African art practiced by the Southern Ndebele people of South Africa and the Northern Ndebele people in Zimbabwe in Matobo. It is predominantly practiced by the Ndebele women.

South African Bantu-speaking peoples represent the majority ethno-racial group of South Africans. Occasionally grouped as Bantu, the term itself is derived from the English word "people", common to many of the Bantu languages. The Oxford Dictionary of South African English describes "Bantu", when used in a contemporary usage or racial context as "obsolescent and offensive", because of its strong association with the "white minority rule" with their Apartheid system. However, Bantu is used without pejorative connotations in other parts of Africa and is still used in South Africa as the group term for the language family.

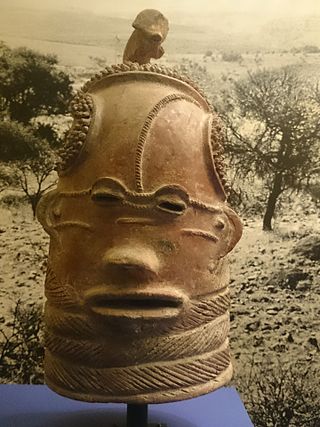

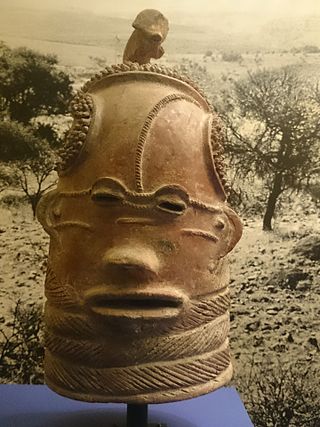

The Luvale people, also spelled Lovale, Balovale, Lubale, as well as Lwena or Luena in Angola, are a Bantu ethnic group found in northwestern Zambia and southeastern Angola. They are closely related to the Lunda and Ndembu to the northeast, but they also share cultural similarities to the Kaonde to the east, and to the Chokwe and Luchazi, important groups of eastern Angola.

The Xhosa people, or Xhosa-speaking people are a Bantu ethnic group native to South Africa. They are the second largest ethnic group in Southern Africa and are native speakers of the IsiXhosa language.

AmaNdebele are an ethnic group native to South Africa who speak isiNdebele. They mainly inhabit the provinces of Mpumalanga, Gauteng and Limpopo, all of which are in the northeast of the country. In academia this ethnic group is referred to as the Southern Ndebele to differentiate it from their relatives the Northern Ndebele people of Limpopo and Northwest.

Umxhentso is the traditional dancing of Xhosa people performed mostly by Amagqirha, the traditional healers/Sangoma. Ukuxhentsa-Dancing has always been a source of pride to the Xhosas as they use this type of dancing in their ceremonies.

The isidwaba, a traditional Zulu leather skirt worn by married women, is made from the hide of animals that belonged to the woman's father. This article will illustrate how the traditional skirt is made and at which occasions it is worn. It further describes the various designs and patterns of an isidwaba and how they are perceived in society, including the symbolic anthropology associations of the isidwaba.

Intonjane is a Xhosa rite of passage into womanhood practiced in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. The ritual takes place after a girl has had her first period. This ritual is symbolic of a girl's sexual maturity and ability to conceive. It is through this ritual that girls are taught about socially accepted behaviours of Xhosa women, while also encouraging them not to have sex before marriage. The origin of the name intonjane is associated with the life cycle of a stick insect. At the end of its larval stage, caterpillars encase themselves in a little grass-like mat cocoon until they are ready to emerge as adults. During these months, trees have these grassy cocoons that Xhosa people refer to as ntonjane. The kind of grass that the girl sits on during the ritual, called inxkopho, bears a resemblance to the cocoons encasing of the caterpillars on the tree, hence the name intonjane. The intonjane ritual takes three to six weeks, and several events take place during that period.

Inqawe is the Xhosa term for the traditional smoking pipe used among the Xhosa people. The pipes come in many variations but are mostly made from Acacia caffra or ‘mnyamanzi’ which is commonly found in the Eastern Cape. Xhosa men and women carry a pipe in a beaded tobacco bag called ‘inxili’ as part of their traditional attire when they attend rituals and traditional functions.

Letsoku is a clayey soil used by several tribes in Southern Africa and other parts of the African continent.The Sotho-Tswana of Southern Africa have described a number of clay soils as letsoku. These are named differently by other tribes in the region, it is known as chomane in Shona, ilibovu in Swati, imbola in Xhosa and luvhundi in Venda, there are many other names given by other ethnic groups. Letsoku occurs naturally in a number of colours and it has many use, it is mostly used for cosmetic applications in Southern Africa. However, other functions of it is related to artwork, medicinal use, cultural symbolism and traditional beliefs

Waist beads is a type of jewelry worn around the waist or on the hips originating from West Africa, they are traditionally worn by women as a symbol of beauty, sexuality, femininity, fertility, well-being or maturity.

Ukusina is a type of traditional dance that has its roots in South Africa's coastal region. For the Zulu people, it is an expressive and rhythmic dance form with deep cultural importance. The Ukusina requires dancers to kick their legs in any direction up and out, and then stamp each foot into the ground. The majority of the time, this dance is performed for entertainment during social occasions such as wedding ceremony. Ukusina dances, as a result, are socially created and center on the song leader singing interlocking word phrases. Traditionally, it was thought that no religious event would be complete without at least one ukusina dance performance. Ukusina dance is a fundamental component of the social, religious, and cultural life of the Zulu people, as evidenced by the descriptions of traditional dances in South Africa. Everyone in attendance is drawn into a coherent action atmosphere by the intimate relationship between body movement and music.