Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. The method in which these threads are interwoven affects the characteristics of the cloth. Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.

Kente refers to a Ghanaian textile made of hand-woven strips of silk and cotton. Historically the fabric was worn in a toga-like fashion among the Asante, Akan and Ewe people. According to Asante oral tradition, it originated from Bonwire in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. In modern day Ghana, the wearing of kente cloth has become widespread to commemorate special occasions, and kente brands led by master weavers are in high demand.

Ikat is a dyeing technique from Southeast Asia used to pattern textiles that employs resist dyeing on the yarns prior to dyeing and weaving the fabric. In Southeast Asia, where it is the most widespread, ikat weaving traditions can be divided into two general groups of related traditions. The first is found among Daic-speaking peoples. The second, larger group is found among the Austronesian peoples and spread via the Austronesian expansion to as far as Madagascar. It is most prominently associated with the textile traditions of Indonesia in modern times, from where the term ikat originates. Similar unrelated dyeing and weaving techniques that developed independently are also present in other regions of the world, including India, Central Asia, Japan, Africa, and the Americas.

Damask is a woven, reversible patterned fabric. Damasks are woven by periodically reversing the action of the warp and weft threads. The pattern is most commonly created with a warp-faced satin weave and the ground with a weft-faced or sateen weave. Yarns used to create damasks include silk, wool, linen, cotton, and synthetic fibers, but damask is best shown in cotton and linen. Over time, damask has become a broader term for woven fabrics with a reversible pattern, not just silks.

Jamdani is a fine muslin textile produced for centuries in South Rupshi of Narayanganj district in Bangladesh on the bank of Shitalakhwa river.

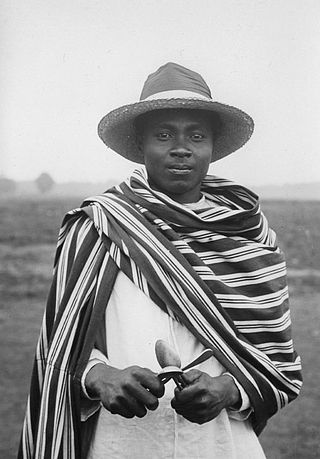

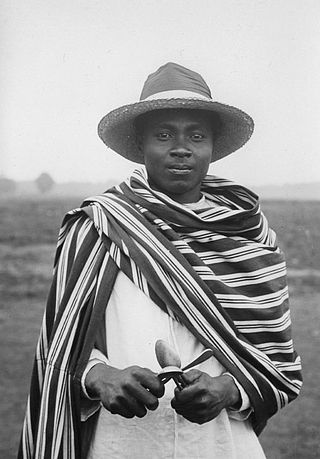

The wrapper, lappa, or pagne is a colorful garment widely worn in West Africa by both men and women. It has formal and informal versions and varies from simple draped clothing to fully tailored ensembles. The formality of the wrapper depends on the fabric used to create or design it.

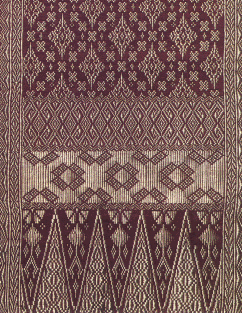

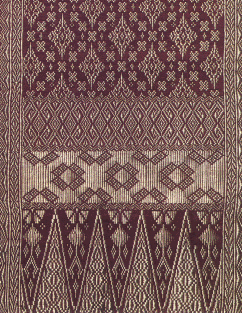

Songket or sungkit is a tenun fabric that belongs to the brocade family of textiles of Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia. It is hand-woven in silk or cotton, and intricately patterned with gold or silver threads. The metallic threads stand out against the background cloth to create a shimmering effect. In the weaving process the metallic threads are inserted in between the silk or cotton weft (latitudinal) threads in a technique called supplementary weft weaving technique.

Maya textiles (k’apak) are the clothing and other textile arts of the Maya peoples, indigenous peoples of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Belize. Women have traditionally created textiles in Maya society, and textiles were a significant form of ancient Maya art and religious beliefs. They were considered a prestige good that would distinguish the commoners from the elite. According to Brumfiel, some of the earliest weaving found in Mesoamerica can date back to around 1000–800 BCE.

In India, about 97% of the raw mulberry silk is produced in the Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. Mysore and North Bangalore, the upcoming site of a US$20 million "Silk City", contribute to a majority of silk production. Another emerging silk producer is Tamil Nadu in the place in where mulberry cultivation is concentrated in Salem, Erode and Dharmapuri districts. Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh and Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu were the first locations to have automated silk reeling units.

The manufacture of textiles is one of the oldest of human technologies. To make textiles, the first requirement is a source of fiber from which a yarn can be made, primarily by spinning. The yarn is processed by knitting or weaving, with color and patterns, which turns it into cloth. The machine used for weaving is the loom. For decoration, the process of coloring yarn or the finished material is dyeing. For more information of the various steps, see textile manufacturing.

African textiles are textiles from various locations across the African continent. Across Africa, there are many distinctive styles, techniques, dyeing methods, and decorative and functional purposes. These textiles hold cultural significance and also have significance as historical documents of African design.

Adire (Yoruba) textile is a type of dyed cloth from south west Nigeria traditionally made by Yoruba women, using a variety of resist-dyeing techniques. The word 'Adire' originally derives from the Yoruba words 'adi' which means to tie and 're' meaning to dye. It is a material designed with wax-resist methods that produce patterned designs in dazzling arrays of tints and hues. It is common among the Egba people of Ogun State.

Aso oke fabric, is a hand-woven cloth that originated from the ijebu people of western Nigeria. Usually woven by men, the fabric is used to make men's gowns, called agbada and hats, called fila, as well as Yoruba women's wrappers called Iro and a Yoruba women's blouse called Buba and a gown called Komole, as well as a head tie, called gele and so on.

The Andean textile tradition once spanned from the Pre-Columbian to the Colonial era throughout the western coast of South America, but was mainly concentrated in what is now Peru. The arid desert conditions along the coast of Peru have allowed for the preservation of these dyed textiles, which can date to 6000 years old. Many of the surviving textile samples were from funerary bundles, however, these textiles also encompassed a variety of functions. These functions included the use of woven textiles for ceremonial clothing or cloth armor as well as knotted fibers for record-keeping. The textile arts were instrumental in political negotiations, and were used as diplomatic tools that were exchanged between groups. Textiles were also used to communicate wealth, social status, and regional affiliation with others. The cultural emphasis on the textile arts was often based on the believed spiritual and metaphysical qualities of the origins of materials used, as well as cosmological and symbolic messages within the visual appearance of the textiles. Traditionally, the thread used for textiles was spun from indigenous cotton plants, as well as alpaca and llama wool.

The textiles of Mexico have a long history. The making of fibers, cloth and other textile goods has existed in the country since at least 1400 BCE. Fibers used during the pre-Hispanic period included those from the yucca, palm and maguey plants as well as the use of cotton in the hot lowlands of the south. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Spanish introduced new fibers such as silk and wool as well as the European foot treadle loom. Clothing styles also changed radically. Fabric was produced exclusively in workshops or in the home until the era of Porfirio Díaz, when the mechanization of weaving was introduced, mostly by the French. Today, fabric, clothes and other textiles are both made by craftsmen and in factories. Handcrafted goods include pre-Hispanic clothing such as huipils and sarapes, which are often embroidered. Clothing, rugs and more are made with natural and naturally dyed fibers. Most handcrafts are produced by indigenous people, whose communities are concentrated in the center and south of the country in states such as Mexico State, Oaxaca and Chiapas. The textile industry remains important to the economy of Mexico although it has suffered a setback due to competition by cheaper goods produced in countries such as China, India and Vietnam.

A lamba is the traditional garment worn by men and women that live in Madagascar. The textile, highly emblematic of Malagasy culture, consists of a rectangular length of cloth wrapped around the body.

Amuzgo textiles are those created by the Amuzgo indigenous people who live in the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca. The history of this craft extends to the pre-Columbian period, which much preserved, as many Amuzgos, especially in Xochistlahuaca, still wear traditional clothing. However, the introduction of cheap commercial cloth has put the craft in danger as hand woven cloth with elaborate designs cannot compete as material for regular clothing. Since the 20th century, the Amuzgo weavers have mostly made cloth for family use, but they have also been developing specialty markets, such as to collectors and tourists for their product.

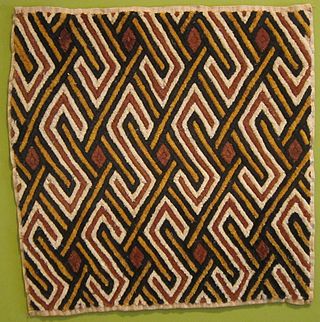

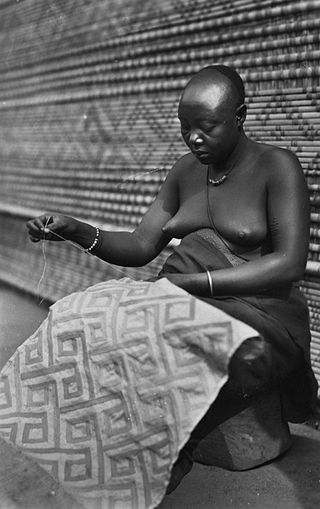

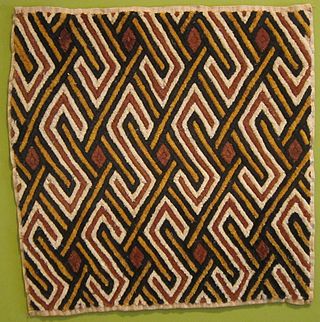

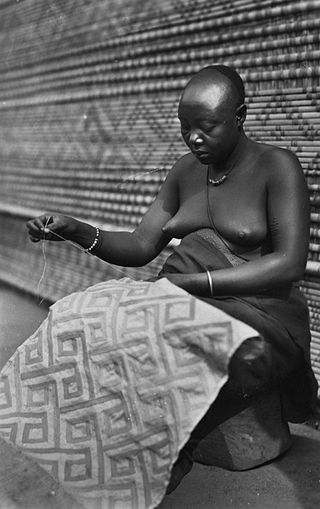

Kuba textiles are a type of raffia cloth unique to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaire, and noted for their elaboration and complexity of design and surface decoration. Most textiles are a variation on rectangular or square pieces of woven palm leaf fiber enhanced by geometric designs executed in linear embroidery and other stitches, which are cut to form pile surfaces resembling velvet. Traditionally, men weave the raffia cloth, and women are responsible for transforming it into various forms of textiles, including ceremonial skirts, ‘velvet’ tribute cloths, headdresses and basketry.

Malagasy textile arts flourished until around 1950. Due to varied ecology in Madagascar, many different materials were used to weave with and formed various styles of mainly striped cloth.

Aso Olona is a traditional Yoruba textile known for its intricate geometric patterns and cultural significance, particularly among the Ijebu subgroup. The term "Aso Olona" translates to "cloth with patterns" in the Yoruba language. Aso Olona is an handwoven fabrics that can come with motifs like the chameleon.