Research contribution

Early work on the psychological reality of linguistic rules.

Kennedy's early research (much of it in collaboration with A. L. Wilkes) was concerned with the "psychological reality" of linguistic competence, a preoccupation of cognitive psychologists in the 1970s. This work made use of simple laboratory tasks involving pressing buttons to indicate whether sentence fragments were grammatical or not, or to signal the presence of a particular word in a sentence. [6]

Eye movement control and reading

In 1972, Kennedy spent six months in Paris, coming into contact with members of "Groupe Regard", an informal network of researchers working on psychological issues relating to eye movement control and led by Arianne Levy-Schoen. On his return to Dundee, Kennedy set up an eye movement laboratory aiming to replace indirect measurement of reaction time with more direct measurements of eye movements as participants read text. Initially, the principal UK funding agency (the Social Science Research Council) saw no future in work on eye movement control and refused to fund it. The validity of the approach was eventually accepted following a series of highly influential publications from laboratories in the USA (in particular, work by Keith Rayner and colleagues. In 1979 Kennedy secured funding and a series of papers in collaboration with Wayne S. Murray confirmed that both the duration and location of eye fixations were controlled by linguistic properties of the text being read. [7]

Spatial coding

The psychological community rapidly established a consensus view that when a reader made an incorrect syntactic attachment (or was induced to do so by some experimental manipulation), this led to the deployment of corrective eye movements, involving looking back at the point in the text where the defective attachment had been made. In 1981, at a Sloan Conference in Amherst, Kennedy pointed out that although this equivalence between re-inspection and syntactic correction seems plausible, it also involves a paradox. This can be illustrated by considering a sentence such as:

While Mary was mending the old grandfather clock struck twelve

The words old grandfather clock may initially be attached as the direct object of the verb mending. The missing comma encourages this error. The fact that the attachment is incorrect becomes apparent when the word struck is encountered. The reader needs to re-analyse the sentence and there is ample experimental evidence that this process of re-analysis may be associated with re-inspecting eye movements (sometimes called "regressions"). For example, an eye movement may be made from the word struck back to the word mending.

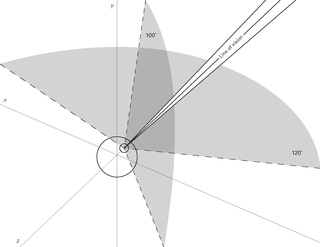

Consideration of how eye movements in reading are controlled exposes a problem with this account. Visual acuity is restricted, so the question of how the eyes can be selectively and accurately directed to particular words arises. When the target is so visually degraded as to be virtually invisible, how is this achieved? Furthermore, if the target of such reinspections is the point where a faulty attachment was made, does this not imply that the reader was, in some sense, already aware of the potential problem?

Kennedy suggested a possible solution to this paradox: the proposal that readers retain information on the spatial disposition of elements of text. This Spatial Coding Theory has proved controversial with researchers claiming either that no spatial information is maintained or that only very primitive non-specific information is retained. [8]

Parafoveal-on-Foveal Effects

In 1995 in a poster presentation at the AmLap Conference in Edinburgh, Kennedy presented evidence that the duration of an eye fixation on a given word could be directly affected by properties (in this case, its frequency of occurrence in the language) of an adjacent word that had not yet been inspected. Up until that time it had been widely accepted that un-fixated words could be pre-processed (the so-called "preview effect"), but any advantage gained from this preview only became evident when the reader actually fixated the next word. The issue was important because of the developing consensus at that time that reading was best characterised as a serial activity in which only one word at a time was attended and all the processing needed to identify that word was completed before the eyes moved on. A preview effect is not inconsistent with this position because the reader’s eyes lag behind the reader’s attention. Attention shifts to the next word while the relevant eye movement is being prepared.

In contrast, evidence that properties of an un-fixated word feed back and directly affect processing time on a currently-fixated word would be seriously damaging to the serial position. Kennedy published the first study demonstrating such "parafoveal-on-foveal" effects in 1998. This was followed by a number of further laboratory studies (most in collaboration with Joël Pynte in Aix-en-Provence) revealing a large number of sources of mutual cross-talk involving adjacent words in text. Factors identified included frequency-of-occurrence, familiarity, the constraint of the initial letters (i.e. how many other words in the language share the same initial letters), and the plausibility of the target sentence-frame.

The initial response from proponents of the strictly serial view of reading to these data was to acknowledge that some mutual interactions between adjacent words might occur, but to claim that the effects were small and fugitive – restricted to the unusual presentation conditions typically found in small-scale experiments (e.g. short sentences on a single line across a computer display). It was claimed that parafoveal-on-foveal interactions were not found in normal reading, and the bulk of evidence at that time supported this contention.

This changed, however, with the publication of an analysis of the Dundee Corpus by Kennedy and Pynte published in 2005. This involved French and English readers working through extended passages of text taken from newspaper articles. Shortly afterwards, Kliegl and colleagues in the University of Potsdam published an even larger analysis of a huge corpus of eye movement data collected during the reading of lengthy passages of text in German. Both the Dundee and Potsdam analyses revealed clear evidence of parafoveal-on-foveal effects. An obvious conclusion is that, rather than characterise the reader’s attention as a "switch" operating in a strictly serial fashion, it seems more plausible that a degree of parallel processing takes place, involving the simultaneous processing of more than one word.

Up to the present, this controversy has not been settled. Although the effects obtained are clearly not an artefact of small-scale laboratory procedures, it must be accepted they are small; it is still possible that artefacts may be involved. One such draws on the fact that eye movement control in normal reading is not particularly precise: sometimes fixations intended for the next word may miss their target. A sufficiently large number of systematic mislocations of this kind might mimic measured parafoveal-on-foveal effects, reducing them to the status of a systematic measurement error. Unfortunately, details of a mechanism that would produce this outcome in practice are lacking. It has also not gone un-noticed that the argument involves a considerable shift of ground, with cross-talk now being seen as characteristic of normal, rather than laboratory, reading. Furthermore, recent evidence that cross-talk varies as a function of the class and syntactic function of the words involved makes an explanation in terms of mislocation implausible.

A critical question in the debate between proponents of serial and parallel views of reading is how the reader arrives relatively effortlessly at a single coherent understanding of the meaning of text. From the serial perspective reading is a sort of "surrogate listening", in which an orderly pattern of inspection delivers the message in the correct order: the problem is the pattern of inspection is usually anything but orderly. From the parallel perspective the meaning of several words becomes available simultaneously: the problem is how are these competing signals resolved into a single correct meaning? [9]

Serial Order in reading

Together with colleagues (in particular Joël Pynte in Paris) Kennedy has recently addressed the problem of serial order in reading head on. Proponents of the view that reading is a kind of "surrogate listening" assume that the reader deals with each word in a strict serial order. You either process a word while looking directly at it, or, in certain cases, manage to attend to the next word without ever looking at it directly (in which case the word concerned may be skipped). In both circumstances words are processed, either overtly or covertly, in their correct serial order. Furthermore, this is a necessary order: the phrases "run home" and "home run" mean quite different things and the only way the two meanings can be disambiguated is to ensure they are looked at in the right order.

Notwithstanding the superficial appeal of this position, Kennedy points out that the claim conflicts with the way people actually look at printed text. Real patterns of inspection are relatively chaotic. For example, words are often looked at several times (particularly so for the beginner); the eyes sometimes jump back several words and re-examine segments of text already processed; the reader may return to words that had been skipped; and so on. In fact it has been known for more than twenty years that a strictly serial pattern of word-to-word inspection makes up only a minority of cases, accounting for about twenty percent of all eye fixations. This is obviously an uncomfortable notion for proponents of the metaphor of the reader as listener, but it also poses some severe challenges for all theories of reading. If readers look at words in a haphazard way and process several at the same time, how do they manage to arrive at a single coherent understanding of what they are reading? Why is this chaotic pattern of inspection not reflected in a chaotic jumble of meanings? As some have argued, encoding multiple words simultaneously in reading seems implausible.

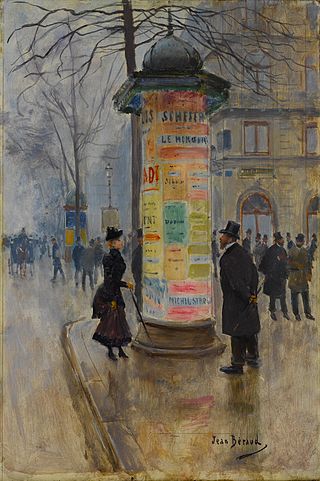

Part of the answer may found by noting that printed text is not at all like the auditory stimulus we process when listening. For one thing, it is stable and relatively permanent: unlike speech, it remains out there, available to be re-examined at will. Text is not distributed in time; it is distributed in space, like a picture. When we look at a picture the claim that we encode multiple meanings simultaneously does not seem at all implausible because the visual system is designed to process objects in parallel. To take a concrete example, when we look at a tree, the temporal order of the fixations that fall on it is of no concern at all. It will be seen as a tree whatever the pattern of inspection. In fact there is little or no evidence for what might be termed a canonical scanpath, or "right way of looking", for a given object. Obviously, particular words convey particular meanings, but the fact that the medium (printed text) is spatially extended means that these meanings can be allocated to specific locations in space. The problem of multiple simultaneous representations disappears once it is accepted that their "simultaneity" is spatial, rather than temporal.

The work of Kennedy and Pynte on non-canonical order in reading has proved controversial and has provoked a vigorous response from proponents of the serial view of reading. [10]