History

Until the second half of the 19th century, researchers had at their disposal three methods of investigating eye movement. The first, unaided observation, yielded only small amounts of data that would be considered unreliable by today's scientific standards. This lack of reliability arises from the fact that eye movement occurs frequently, rapidly, and over small angles, to the extent that it is impossible for an experimenter to perceive and record the data fully and accurately without technological assistance. The other method was self-observation, now considered to be of doubtful status in a scientific context. Despite this, some knowledge appears to have been produced from introspection and naked-eye observation. For example, Ibn al Haytham, a medical man in 11th-century Egypt, is reported to have written of reading in terms of a series of quick movements and to have realised that readers use peripheral as well as central vision. [1]

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) may have been the first in Europe to recognize certain special optical qualities of the eye. He derived his insights partly through introspection but mainly through a process that could be described as optical modelling. Based on dissection of the human eye he made experiments with water-filled crystal balls. He wrote "The function of the human eye, ... was described by a large number of authors in a certain way. But I found it to be completely different." [2]

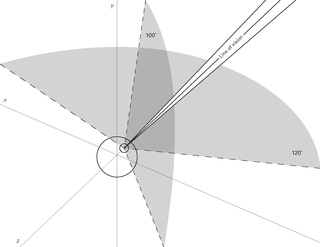

His main experimental finding was that there is only distinct and clear vision at the "line of sight", the optical axis that ends at the fovea. Although he did not use these words literally he actually is the father of the modern distinction between foveal vision (where the observer fixates on the object of interest) and peripheral vision. However, Leonardo did not know that the retina is the sensible layer, he still believed that the lens is the organ of vision.

There appear to be no records of eye movement research until the early 19th century. At first, the chief concern was to describe the eye as a physiological and mechanical moving object, the most serious attempt being Hermann von Helmholtz's major work Handbook of physiological optics (1866). The physiological approach was gradually superseded by interest in the psychological aspects of visual input, in eye movement as a functional component of visual tasks.

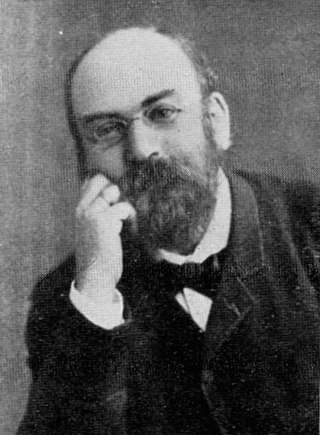

The subsequent decades saw more elaborate attempts to interpret eye movement, including a claim that meaningful text requires fewer fixations to read than random strings of letters. [3] In 1879, the French ophthalmologist Louis Émile Javal used a mirror on one side of a page to observe eye movement in silent reading, and found that it involves a succession of discontinuous individual movements for which he coined the term saccades. In 1898, Erdmann & Dodge used a hand-mirror to estimate average fixation duration and saccade length with surprising accuracy.

Early tracking technology

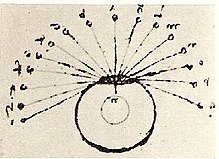

Eye tracking device is a tool created to help measure eye and head movements. The first devices for tracking eye movement took two main forms: those that relied on a mechanical connection between participant and recording instrument, and those in which light or some other form of electromagnetic energy was directed at the participant's eyes and its reflection measured and recorded. In 1883, Lamare was the first to use a mechanical connection, by placing a blunt needle on the participant's upper eyelid. The needle picked up the sound produced by each saccade and transmitted it as a faint clicking to the experimenter's ear through an amplifying membrane and a rubber tube. The rationale behind this device was that saccades are easier to perceive and register aurally than visually. [4] In 1889, Edmund B. Delabarre invented a system of recording eye movement directly onto a rotating drum by means of a stylus with a direct mechanical connection to the cornea. [5] Other devices involving physical contact with the surface of the eyes were developed and used from the end of the 19th century until the late 1920s; these included such items as rubber balloons and eye caps.

Mechanical systems suffered three serious disadvantages: questionable accuracy due to slippage of the physical connection, the considerable discomfort caused to participants by the direct mechanical connection (and consequently great difficulty in persuading people to participate), and issues of ecological validity, since participants' experience of reading in trials was significantly different from the normal reading experience. Despite these drawbacks, mechanical devices were used in eye movement research well into the 20th century.

Attempts were soon made to overcome these problems. One solution was to use electromagnetic energy rather than a mechanical connection. In the "Dodge technique", a beam of light was directed at the cornea, focused by a system of lenses and then recorded on a moveable photographic plate. Erdmann & Dodge [6] used this technique to claim that there is little or no perception during saccades, a finding that was later confirmed by Utall & Smith using more sophisticated equipment. The photographic plate in the Dodge technique was soon replaced with a film camera, but was still plagued by problems of accuracy, due to the difficulty of keeping all parts of the equipment perfectly aligned throughout a trial and accurately compensating for the distortion caused by the diffractive qualities of photographic lenses. In addition, it was usually necessary to restrain a participant's head by using an uncomfortable bite-bar or head-clamp.

In 1922, Schott pioneered a further advance called electro-oculography (EOG), a method of recording the electrical potential between the cornea and the retina. [7] Electrodes may be covered with special contact paste before being placed on the skin. So, it is now unnecessary to make incisions in patient's skin. A common misconception about EOG is that the measured potential is the electromyogram of extraocular muscles. In fact, it is only the projection of eye dipole to the skin, because higher frequencies, corresponding to EMG, are filtered out. EOG delivered considerable improvements in accuracy and reliability, which explain its continued use by experimentalists for many decades. [8] [9] [10]