The rules of chess govern the play of the game of chess. Chess is a two-player abstract strategy board game. Each player controls sixteen pieces of six types on a chessboard. Each type of piece moves in a distinct way. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent's king. A game can end in various ways besides checkmate: a player can resign, and there are several ways a game can end in a draw.

Descriptive notation is a chess notation system based on abbreviated natural language. Its distinctive features are that it refers to files by the piece that occupies the back rank square in the starting position and that it describes each square two ways depending on whether it is from White or Black's point of view. It was common in English, Spanish and French chess literature until about 1980. In most other languages, the more concise algebraic notation was in use. Since 1981, FIDE no longer recognizes descriptive notation for the purposes of dispute resolution, and algebraic notation is now the accepted international standard.

A chess problem, also called a chess composition, is a puzzle set by the composer using chess pieces on a chess board, which presents the solver with a particular task. For instance, a position may be given with the instruction that White is to move first, and checkmate Black in two moves against any possible defence. A chess problem fundamentally differs from over-the-board play in that the latter involves a struggle between Black and White, whereas the former involves a competition between the composer and the solver. Most positions which occur in a chess problem are 'unrealistic' in the sense that they are very unlikely to occur in over-the-board play. There is a good deal of specialized jargon used in connection with chess problems.

This glossary of chess explains commonly used terms in chess, in alphabetical order. Some of these terms have their own pages, like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of named opening lines, see List of chess openings; for a list of chess-related games, see List of chess variants; for a list of terms general to board games, see Glossary of board games.

A Babson task is a directmate chess problem with the following properties:

- White has only one key, or first move, that forces checkmate in the stipulated number of moves.

- Black's defences include the promotion of a certain pawn to a queen, rook, bishop, or knight.

- If Black promotes, then White must promote a pawn to the same piece to which Black promoted in order to complete the solution.

This glossary of chess problems explains commonly used terms in chess problems, in alphabetical order. For a list of unorthodox pieces used in chess problems, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms used in chess is general, see Glossary of chess; for a list of chess-related games, see List of chess variants.

A Grimshaw is a device found in chess problems in which two pieces arriving on a particular square mutually interfere with each other. It is named after the 19th-century problem composer Walter Grimshaw. The Grimshaw is one of the most common devices found in directmates.

The Novotny is a device found in chess problems named after a problem from 1854 by Antonín Novotný, though the first example was composed by Henry Turton in 1851. A piece is sacrificed on a square where it could be taken by two different opposing pieces, but whichever makes the capture, it interferes with the other. It is essentially a Grimshaw brought about by a sacrifice on the critical square.

The Immortal Game was a game of chess, played in 1851 by Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky. It was played while the London 1851 chess tournament was in progress, an event in which both players participated. However, the Immortal Game was itself a casual game, not played as part of the tournament. Anderssen won the game by allowing a double rook sacrifice, a major loss of material, while also developing a mating attack with his remaining minor pieces. Despite losing the game, Kieseritzky was impressed with Anderssen's performance. Shortly after it was played, Kieseritzky published the game in La Régence, a French chess journal which he helped to edit. In 1855, Ernst Falkbeer published an analysis of the game, describing it for the first time with its namesake "immortal".

A proof game is a type of retrograde analysis chess problem. The solver must construct a game starting from the initial chess position, which ends with a given position after a specified number of moves. A proof game is called a shortest proof game if no shorter solution exists. In this case the task is simply to construct a shortest possible game ending with the given position.

In chess, the scholar's mate is the checkmate achieved by the following moves, or similar:

In chess, a back-rank checkmate is a checkmate delivered by a rook or queen along a back rank in which the mated king is unable to move up the board because the king is blocked by friendly pieces on the second rank. A typical position is shown to the right.

In chess problems, retrograde analysis is a technique employed to determine which moves were played leading up to a given position. While this technique is rarely needed for solving ordinary chess problems, there is a whole subgenre of chess problems in which it is an important part; such problems are known as retros.

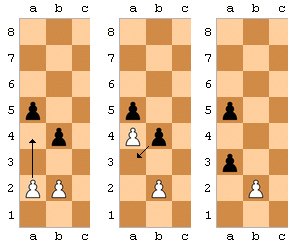

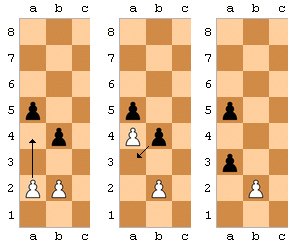

En passant is a special method of capturing in chess that occurs when a pawn captures a horizontally adjacent enemy pawn that has just made an initial two-square advance. The capturing pawn moves to the square that the enemy pawn passed over, as if the enemy pawn had advanced only one square. The rule ensures that a pawn cannot use its two-square move to safely skip past an enemy pawn.

In chess, a cross-check is a tactic in which a check is played in response to a check, especially when the original check is blocked by a piece that itself either delivers check or reveals a discovered check from another piece. Sometimes the term is extended to cover cases in which the king moves out of check and reveals a discovered check from another piece ; it does not generally apply to cases where the original checking piece is captured.

In chess, promotion is the replacement of a pawn with a new piece when the pawn is moved to its last rank. The player replaces the pawn immediately with a queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color. The new piece does not have to be a previously captured piece. Promotion is mandatory; the pawn cannot remain as a pawn.

Joke chess problems are puzzles in chess that use humor as a primary or secondary element. Although most chess problems, like other creative forms, are appreciated for serious artistic themes, joke chess problems are enjoyed for some twist. In some cases the composer plays a trick to prevent a solver from succeeding with typical analysis. In other cases, the humor derives from an unusual final position. Unlike in ordinary chess puzzles, joke problems can involve a solution which violates the inner logic or rules of the game.

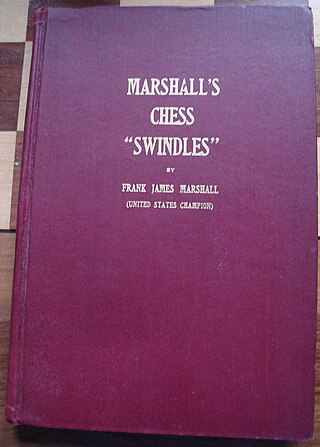

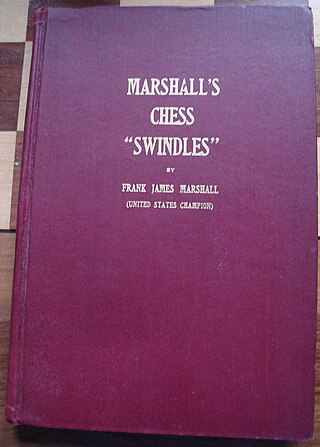

In chess, a swindle is a ruse by which players in a losing position trick their opponent and thereby achieve a win or draw instead of the expected loss. It may also refer more generally to obtaining a win or draw from a clearly losing position. I. A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld distinguish among "traps", "pitfalls", and "swindles". In their terminology, a "trap" refers to a situation where players go wrong through their own efforts. In a "pitfall", the beneficiary of the pitfall plays an active role, creating a situation where a plausible move by the opponent will turn out badly. A "swindle" is a pitfall adopted by a player who has a clearly lost game. Horowitz and Reinfeld observe that swindles, "though ignored in virtually all chess books", "play an enormously important role in over-the-board chess, and decide the fate of countless games".

Omega Chess is a commercial chess variant designed and released in 1992 by Daniel MacDonald. The game is played on a 10×10 board with four extra squares, each added diagonally adjacent to the corner squares. The game is laid out like standard chess with the addition of a champion in each corner of the 10×10 board and a wizard in each new added corner square.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to chess: