Related Research Articles

Chiang Kai-shek was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and military commander who was the leader of the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party and commander-in-chief and Generalissimo of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) from 1926, and leader of the Republic of China (ROC) in mainland China from 1928. After Chiang was defeated in the Chinese Civil War by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1949, he continued to lead the Republic of China on the island of Taiwan until his death in 1975. He was considered the legitimate head of China by the United Nations until 1971.

Soong Mei-ling, also known as Madame Chiang, was a Chinese political figure. The youngest of the Soong sisters, she married Chiang Kai-shek and played a prominent role in Chinese politics and foreign relations in the first half of the 20th century.

Wang Zhaoming, widely known by his pen name Wang Jingwei, was a Chinese politician who was president of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China, a puppet state of the Empire of Japan. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang (KMT), leading a government in Wuhan in opposition to the right-wing Nationalist government in Nanjing, but later became increasingly anti-communist after his efforts to collaborate with the Chinese Communist Party ended in political failure.

The United States Senate's Special Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, 1951–77, known more commonly as the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) and sometimes the McCarran Committee, was authorized by S. 366, approved December 21, 1950, to study and investigate (1) the administration, operation, and enforcement of the Internal Security Act of 1950 and other laws relating to espionage, sabotage, and the protection of the internal security of the United States and (2) the extent, nature, and effects of subversive activities in the United States "including, but not limited to, espionage, sabotage, and infiltration of persons who are or may be under the domination of the foreign government or organization controlling the world Communist movement or any movement seeking to overthrow the Government of the United States by force and violence". The resolution also authorized the subcommittee to subpoena witnesses and require the production of documents. Because of the nature of its investigations, the subcommittee is considered by some to be the Senate equivalent to the older House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

Chen Cheng, courtesy name Tsi-siou, was a Chinese political and military leader, and one of the main commanders of the National Revolutionary Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War.

Owen Lattimore was an American Orientalist and writer. He was an influential scholar of China and Central Asia, especially Mongolia. Although he never earned a college degree, in the 1930s he was editor of Pacific Affairs, a journal published by the Institute of Pacific Relations, and taught at Johns Hopkins University from 1938 to 1963. He was director of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations from 1939 to 1953. During World War II, he was an advisor to Chiang Kai-shek and the American government and contributed extensively to the public debate on U.S. policy toward Asia. From 1963 to 1970, Lattimore was the first Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of Leeds in England.

Patrick Jay Hurley was an American politician and diplomat. He was the United States Secretary of War from 1929 to 1933, but is best remembered for being Ambassador to China in 1945, during which he was instrumental in getting Joseph Stilwell recalled from China and replaced with the more diplomatic General Albert Coady Wedemeyer. A man of humble origins, Hurley's lack of what was considered to be a proper ambassadorial demeanor and mode of social interaction made professional diplomats scornful of him. He came to share pre-eminent army strategist Wedemeyer's view that the Chinese Communists could be defeated and America ought to commit to doing so even if it meant backing the Kuomintang and Chiang Kai-shek to the hilt. Frustrated, Hurley resigned as Ambassador to the Republic of China in 1945, publicised his concerns about high-ranking members of the State Department, and alleged they believed that the Chinese Communists were not totalitarians and that America's priority was to avoid allying with a losing side in the civil war.

The Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) was an international NGO established in 1925 to provide a forum for discussion of problems and relations between nations of the Pacific Rim. The International Secretariat, the center of most IPR activity over the years, consisted of professional staff members who recommended policy to the Pacific Council and administered the international program. The various national councils were responsible for national, regional and local programming. Most participants were members of the business and academic communities in their respective countries. Funding came largely from businesses and philanthropies, especially the Rockefeller Foundation. IPR international headquarters were in Honolulu until the early 1930s when they were moved to New York and the American Council emerged as the dominant national council.

John Paton Davies Jr. was an American diplomat and Medal of Freedom recipient. He was one of the China Hands, whose careers in the Foreign Service were ended by McCarthyism and the reaction to the loss of China.

The Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact was signed in Nanjing on August 21, 1937, between the Republic of China and the Soviet Union during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The pact went into effect on the day that it was signed and was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on September 8, 1937.

Frederick Vanderbilt Field was an American leftist political activist, political writer and a great-great-grandson of railroad tycoon Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt, disinherited by his wealthy relatives for his radical political views. Field became a specialist on Asia and was a prime staff member and supporter of the Institute of Pacific Relations. He also supported Henry Wallace's Progressive Party and so many openly Communist organizations that he was accused of being a member of the Communist Party. He was a top target of the American government during the peak of 1950s McCarthyism. Field denied ever having been a party member but admitted in his memoirs, "I suppose I was what the Party called a 'member at large.'"

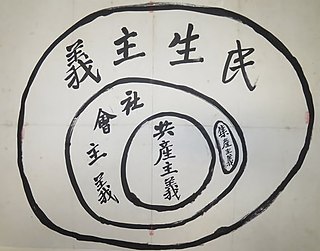

The historical Kuomintang socialist ideology is a form of socialist thought developed in mainland China during the early Republic of China. The Tongmenghui revolutionary organization led by Sun Yat-sen was the first to promote socialism in China.

The Zhucheng Campaign (诸城战役) was a campaign fought in Shandong, and it was a clash between the communists and the former nationalists turned Japanese puppet regime force who rejoined the nationalists after World War II. The battle was one of the Chinese Civil War in the immediate post World War II era, and resulted in communist victory.

In American political discourse, the "loss of China" is the unexpected Chinese Communist Party coming to power in mainland China from the U.S.-backed Nationalist Chinese Kuomintang government in 1949 and therefore the "loss of China to communism."

Lawrence Kaelter Rosinger was an American specialist on modern East Asia, focusing on China and India.

Philip Jacob Jaffe was a communist American businessman, editor and author. He was born in Ukraine and moved to New York City as a child. He became the owner of a profitable greeting card company. In the 1930s Jaffe became interested in Communism and edited two journals associated with the Communist Party USA. He is known for the 1945 Amerasia affair, in which the FBI found classified documents in the offices of his Amerasia magazine that had been given to him by State Department employee John S. Service. He received a minimal sentence due to OSS/FBI bungling of the investigation, but there were continued reviews of the affair by Congress into the 1950s. He later wrote about the rise and decline of the Communist Party in the USA.

Thomas Arthur Bisson, who wrote as T. A. Bisson was an American political writer, journalist, and government official who specialized in East Asian politics and economics.

The Joint Committee Against Communism, also known as the Joint Committee Against Communism in New York, was an anti-communist organization during the 1950s.

The American China Policy Association (ACPA) was an anti-communist organization that supported the government of Republic of China, now commonly referred to as Taiwan, under Chiang Kai-shek.

Joseph C. Keeley (1907–1994) was an American public relations expert who became editor of American Legion magazine (1949-1963) and wrote a biography of Alfred Kohlberg called The China Lobby Man in 1969.

References

- ↑ Herzstein, Robert E. (2006-06-01). "Alfred Kohlberg: Counter-Subversion in the Global Struggle against Communism, 1944-1960" (PDF). Globalization, Empire, and Imperialism in Historical Perspective. University of North Carolina. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ↑ Diamond, Sigmund (1992). Compromised Campus: The Collaboration of Universities with the Intelligence Community, 1945-1955. Oxford University Press. pp. 170, 328 (fn17). ISBN 9780195053821 . Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ↑ Leahy, Stephen M. (3 September 2018). "Alfred J. Kohlberg and the Chaoshan embroidered handkerchief industry, 1922-1957". Social Transformations in Chinese Societies. 14 (2): 45–59. doi:10.1108/STICS-04-2018-0006. S2CID 158677023 . Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Keeley, Joseph C. (1969). "The China lobby Man: The Story of Alfred Kohlberg". Arlington House Publishers. pp. ix (neighbors), xxv (ACPA 1946.07.17, Plain Talk 1946.10), xvi (1951.06.25), 1 (Mandel), 3 (Lattimore, Jessup), 54-71 (ABMAC), 77-93 (IPR), 166-208 (IPR), 233-234 (ACPA vs. IPR), 235 (Clare Booth Luce), 253-253 (SISS testimony), 257 (Mason), 313 (offices), 314 (dozen years). Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ↑ Reynolds, Colin E. (2016). The Not-So-Far Right: Radical Right-Wing Politics in the United States, 1941-1977. Atlanta, GA: Emory University (Ph.D. dissertation).

- ↑ McCarran Committee testimony, April 16, 1952

- ↑ Waskey, Jack (2010). "American China Policy Association". In Song, Yuwu (ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese-American Relations. McFarland. p. 21. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ↑ "Register of the Alfred Kohlberg papers". OAC CDLIB. 1998. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ↑ Krause, Allen (2010). "Rabbi Benjamin Schultz and the American Jewish League Against Communism: From McCarthy to Mississippi". Southern Jewish History. Southern Jewish Historical Society: 167 (quote), 208 (fn25 on founding). Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ↑ Doorey, Marie. "Lawrence Kohlberg: American Psychologist". Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ↑ "A Ifred Kohlberg, Importer, Dies; Fighter Against Communism, 73; Called 'Head of China Lobby'; Led the American Jewish League Against Reds". April 8, 1960. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ↑ "Mrs. Alfred Kohlberg Dies at 71; Widow of 'China Lobby's' Head". The New York Times. February 12, 1968. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ↑ 臺北榮民總醫院院史廳 (2019-05-13). "1963成立柯柏醫學科學研究紀念館". 臺北榮民總醫院院史廳. Retrieved 2024-08-10.