Kolberg is a 1945 Nazi propaganda historical film written and directed by Veit Harlan. One of the last films of the Third Reich, it was intended to bolster the will of the German population to resist the Allies.

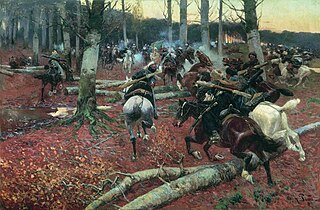

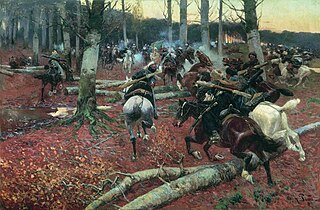

The Caucasian War or the Caucasus War was a 19th-century military conflict between the Russian Empire and various peoples of the North Caucasus who resisted subjugation during the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. It consisted of a series of military actions waged by the Russian Imperial Army and Cossack settlers against the native inhabitants such as the Adyghe, Abaza-Abkhazians, Ubykhs, Chechens, and Dagestanis as the Tsars sought to expand.

Barrier troops, blocking units, or anti-retreat forces are military units that are located in the rear or on the front line to maintain military discipline, prevent the flight of servicemen from the battlefield, capture spies, saboteurs and deserters, and return troops who flee from the battlefield or lag behind their units.

Vladimir Nevezhin is a Russian historian, is working as a professor in Moscow, chief scientific collaborator at the Institute of Russian History and member of the editorial board of the journal Отечественная история.

The Gestapo–NKVD conferences were a series of security police meetings organised in late 1939 and early 1940 by Germany and the Soviet Union, following the invasion of Poland in accordance with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The meetings enabled both parties to pursue specific goals and aims as outlined independently by Hitler and Stalin, with regard to the acquired, formerly Polish territories. The conferences were held by the Gestapo and the NKVD officials in several Polish cities. In spite of their differences on other issues, both Heinrich Himmler and Lavrentiy Beria had similar objectives as far as the fate of pre-war Poland was concerned. The objectives were agreed upon during signing of the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty on 28 September 1939.

Yaroslav Semenovych Stetsko was a Ukrainian politician, writer and ideologist who served as the leader of Stepan Bandera's faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B, from 1941 until his death. During the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, he was named the temporary head of an independent Ukrainian government which was declared in the act of restoration of the Ukrainian state. From 1942 to 1944, he was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. After World War II, Stetsko was the head of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations until his death in 1986.

The Bulgarian Resistance was part of the anti-Axis resistance during World War II. It consisted of armed and unarmed actions of resistance groups against the Wehrmacht forces in Bulgaria and the Tsardom of Bulgaria authorities. It was mainly communist and pro-Soviet Union. Participants in the armed resistance were called partizanin and yatak.

The 383rd 'Miners' Rifle Division was a formation of the Red Army, created during the Second World War. The division was officially created on 18 August 1941. It was given the name Shakhterskaya, as it was originally composed completely of miners from the Donets Basin, Ukrainian SSR. During the course of the war, its losses were continually replaced, and thus it began to consist not only of miners from Donbas.

The 8th Estonian Rifle Corps was a formation in the Red Army, created on 6 November 1942, during World War II.

Alexander Nikolayevich Samokhvalov was a Soviet Russian painter, watercolorist, graphic artist, illustrator, art teacher and Honored Arts Worker of the RSFSR, who lived and worked in Leningrad. He was a member of the Leningrad branch of Union of Artists of Russian Federation, and was regarded as one of the founders and brightest representatives of the Leningrad school of painting, most famous for his genre and portrait painting.

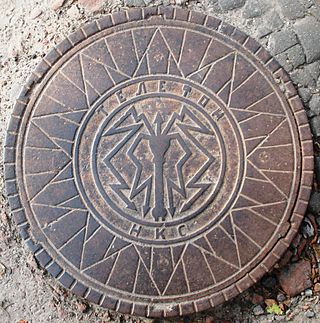

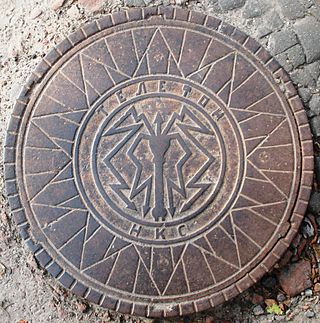

The Ministry of Communications of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (‹See Tfd›Russian: Министерство связи СССР) was the central state administration body on communications in the Soviet Union from 1923 to 1991. During its existence it had three names: People's Commissariat for Posts and Telegraphs (1923–32), People's Commissariat for Communications (1932–46) and Ministry of Communications (1946–1991). It had authority over the postal, telegraph and telephone communications as well as public radio, technical means of radio and television broadcasting, and the distribution of periodicals in the country.

Jasef Alexandrovich Serebriany was a Soviet painter and stage decorator, who lived and worked in Leningrad, a member of the Leningrad Union of Artists, People's Artist of the Russian Federation, professor of the Repin Institute of Arts, regarded as one of the leading representatives of the Leningrad school of painting, well known for his portrait paintings.

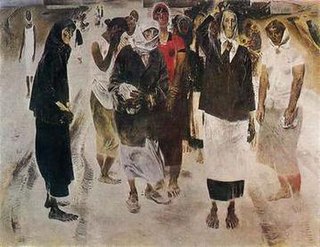

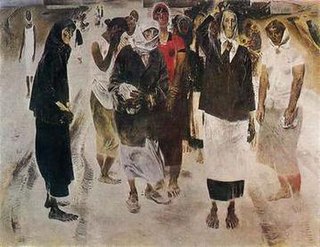

Mothers, Sisters is a 1967 painting by Russian artist Yevsey Moiseyenko (1916–1988).

The People's Commissariat for Communications of the USSR was the central state agency of the Soviet Union for communications in the period 1932 to 1946. The Commissariat administered the postal, telegraph and telephone services.

Yuriy Ivanovich Semenov was a Soviet and Russian historian, philosopher, ethnologist, anthropologist, expert on the history of philosophy, history of primitive society, and the theory of knowledge. He was also the original creator of the globally-formation (relay-stadial) concept of world history and is a Doctor of Philosophy, Doctor of Historical Sciences (1963), and Professor. He was Distinguished Professor at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology.

Fillip Alekseevich Parusinov was a Soviet army group commander. He fought in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I before going over to the Bolsheviks in the subsequent civil war. He was promoted to Polkovnik (colonel) in 1935, Kombrig in 1937, Komdiv in 1938 and Komkor in 1939. He fought in the wars against Finland, Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. He retired in 1956 at the age of 63.

Max Taitz was a Soviet scientist, engineer, and one of the founders of Gromov Flight Research Institute (1941). He was a doctor of engineering, a professor, and a recipient of the Stalin Prize, and the honorary title of Honoured Scientist of the RSFSR (1961).

Fedor Maksimovich Putintsev was a Soviet propagandist of atheism and a scientific worker in the study of problems of religion and atheism. He was also a journalist and writer.

Falsification of history in Azerbaijan is an evaluative definition, which, according to a number of authors, should characterize the historical research carried out in Azerbaijan with state support. The purpose of these studies, according to critics, is to exalt the Caucasian Albanians as the alleged ancestors of Azerbaijanis and to provide a historical basis for territorial disputes with Armenia. At the same time, the task is, firstly, to root Azerbaijanis in the territory of Azerbaijan, and secondly, to cleanse the latter of the Armenian heritage. In the sharpest and most detailed form, these accusations are presented by specialists from Armenia, but the same is said, for example, by Russian historians Victor Schnirelmann, Anatoly Yakobson, Vladimir Zakharov, Mikhail Meltyukhov and others, Iranian historian Hasan Javadi, American historians Philip L. Kohl and George Bournoutian.

The anti-Soviet resistance by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army was a guerrilla war waged by Ukrainian nationalist partisan formations against the Soviet Union in the western regions of the Ukrainian SSR and southwestern regions of the Byelorussian SSR, during and after World War II. With the Red Army forces successful counteroffensive against the Nazi Germany and their invasion into western Ukraine in July 1944, UPA resisted the Red Army's advancement with full-scale guerrilla war, holding up 200,000 Soviet soldiers, particularly in the countryside, and was supplying intelligence to the Nazi Sicherheitsdienst (SD) security service.