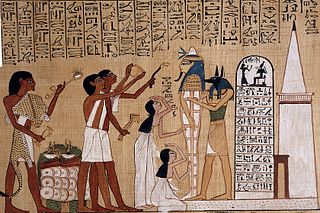

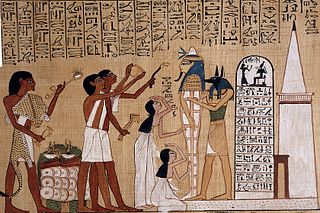

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect the dead, from interment, to various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in their honour. Customs vary between cultures and religious groups. Funerals have both normative and legal components. Common secular motivations for funerals include mourning the deceased, celebrating their life, and offering support and sympathy to the bereaved; additionally, funerals may have religious aspects that are intended to help the soul of the deceased reach the afterlife, resurrection or reincarnation.

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of the living. Some groups venerate their direct, familial ancestors. Certain religious groups, in particular the Eastern Orthodox Churches, Catholic Church and Anglican Church venerate saints as intercessors with God; the latter also believes in prayer for departed souls in Purgatory. Other religious groups, however, consider veneration of the dead to be idolatry and a sin.

The Day of the Dead is a holiday traditionally celebrated on November 1 and 2, though other days, such as October 31 or November 6, may be included depending on the locality. It is widely observed in Mexico, where it largely developed, and is also observed in other places, especially by people of Mexican heritage. The observance falls during the Christian period of Allhallowtide. Some argue that there are Indigenous Mexican or ancient Aztec influences that account for the custom, and it has become a way to remember those forebears of Mexican culture. The Day of the Dead is largely seen as having a festive characteristic. The multi-day holiday involves family and friends gathering to pay respects and to remember friends and family members who have died. These celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played since at least 1650 BC by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modernized version of the game, ulama, is still played by the indigenous populations in some places.

Papantla is a city and municipality located in the north of the Mexican state of Veracruz, in the Sierra Papanteca range and on the Gulf of Mexico. The city was founded in the 13th century by the Totonacs and has dominated the Totonacapan region of the state since then. The region is famed for vanilla, which occurs naturally in this region, the Danza de los Voladores and the El Tajín archeological site, which was named a World Heritage Site. Papantla still has strong communities of Totonacs who maintain the culture and language. The city contains a number of large scale murals and sculptures done by native artist Teodoro Cano García, which honor the Totonac culture. The name Papantla is from Nahuatl and most often interpreted to mean "place of the papanes". This meaning is reflected in the municipality's coat of arms.

Dziady is a term in Slavic folklore for the spirits of the ancestors and a collection of pre-Christian rites, rituals and customs that were dedicated to them. The essence of these rituals was the "communion of the living with the dead", namely, the establishment of relationships with the souls of the ancestors, periodically returning to their headquarters from the times of their lives. The aim of the ritual activities was to win the favor of the deceased, who were considered to be caretakers in the sphere of fertility. The name "dziady" was used in particular dialects mainly in Poland, Belarus, Polesia, Russia, and Ukraine, but under different other names there were very similar ritual practices, common among Slavs and Balts, and also in many European and even non-European cultures.

Preta, also known as hungry ghost, is the Sanskrit name for a type of supernatural being described in Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Chinese folk religion as undergoing suffering greater than that of humans, particularly an extreme level of hunger and thirst. They have their origins in Indian religions and have been adopted into East Asian religions via the spread of Buddhism. Preta is often translated into English as "hungry ghost" from the Chinese and East Asian adaptations. In early sources such as the Petavatthu, they are much more varied. The descriptions below apply mainly in this narrower context. The development of the concept of the preta started with just thinking that it was the soul and ghost of a person once they died, but later the concept developed into a transient state between death and obtaining karmic reincarnation in accordance with the person's fate. In order to pass into the cycle of karmic reincarnation, the deceased's family must engage in a variety of rituals and offerings to guide the suffering spirit into its next life. If the family does not engage in these funerary rites, which last for one year, the soul could remain suffering as a preta for the rest of eternity.

San Andres Míxquic is a community located in the southeast of the Distrito Federal in the borough of Tláhuac. The community was founded by the 11th century on what was a small island in Lake Chalco. “Míxquic” means “in mesquite” but the community's culture for most of its history was based on chinampas, gardens floating on the lake's waters and tied to the island. Drainage of Lake Chalco in the 19th and 20th century eventually destroyed the chinampas but the community is still agricultural in nature, despite being officially in the territory of Mexico City.

All Souls Day, or All Souls Day: Dia de los Muertos, is a 2005 American zombie film written by Mark A. Altman and directed by Jeremy Kasten. It premiered at the 2005 Slamdance Film Festival, and the Sci Fi Channel played it on June 11, 2005. There is also an uncut version on DVD.

Pan de muerto is a type of pan dulce traditionally baked in Mexico and the Mexican diaspora during the weeks leading up to the Día de los Muertos, which is celebrated from November 1 to November 2.

A death anniversary is the anniversary of the death of a person. It is the opposite of birthday. It is a custom in several Asian cultures, including Azerbaijan, Armenia, Cambodia, China, Georgia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, India, Myanmar, Iran, Israel, Japan, Bangladesh, Korea, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Russia, Sri Lanka and Vietnam, as well as in other places with significant overseas Chinese, Japanese, Jewish, Korean, and Vietnamese populations, to observe the anniversary on which a family member or other significant individual died. There are also similar memorial services that are held at different intervals, such as every week.

The Nahua of La Huasteca is an indigenous ethnic group of Mexico and one of the Nahua peoples. They live in the mountainous area called La Huasteca which is located in north eastern Mexico and contains parts of the states of Hidalgo, Veracruz and Puebla. They speak one of the Huasteca Nahuatl dialects: western, central or eastern Huasteca Nahuatl.

Festival of the Dead or Feast of Ancestors is held by many cultures throughout the world in honor or recognition of deceased members of the community, generally occurring after the harvest in August, September, October, or November.

Dogs have occupied a powerful place in Mesoamerican folklore and myth since at least the Classic Period right through to modern times. A common belief across the Mesoamerican region is that a dog carries the newly deceased across a body of water in the afterlife. Dogs appear in underworld scenes painted on Maya pottery dating to the Classic Period and even earlier than this, in the Preclassic, the people of Chupícuaro buried dogs with the dead. In the great Classic Period metropolis of Teotihuacan, 14 human bodies were deposited in a cave, most of them children, together with the bodies of three dogs to guide them on their path to the underworld.

Halloween is a celebration observed on October 31, the day before the feast of All Hallows, also known as Hallowmas or All Saint's Day. The celebrations and observances of this day occur primarily in regions of the Western world, albeit with some traditions varying significantly between geographical areas.

There are extensive and varied beliefs in ghosts in Mexican culture. In Mexico, the beliefs of the Maya, Nahua, Purépecha; and other indigenous groups in a supernatural world has survived and evolved, combined with the Catholic beliefs of the Spanish. The Day of the Dead incorporates pre-Columbian beliefs with Christian elements. Mexican literature and cinema include many stories of ghosts interacting with the living.

Ancient Greek funerary practices are attested widely in literature, the archaeological record, and in ancient Greek art. Finds associated with burials are an important source for ancient Greek culture, though Greek funerals are not as well documented as those of the ancient Romans.

An ofrenda is the offering placed in a home altar during the annual and traditionally Mexican Día de los Muertos celebration. An ofrenda, which may be quite large and elaborate, is usually created by the family members of a person who has died and is intended to welcome the deceased to the altar setting.

Cizin is a Maya god of death and earthquakes. He is the most important Maya death god in the Maya culture. Scholars call him God A.

Formerly in Spain, the pan de ánimas, pan de difunto or pan de muerto were breads that were prepared, blessed and offered to deceased loved ones during All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day.