Tlaloc is the god of rain in Aztec religion. He was also a deity of earthly fertility and water, worshipped as a giver of life and sustenance. This came to be due to many rituals, and sacrifices that were held in his name. He was feared, but not maliciously, for his power over hail, thunder, lightning, and even rain. He is also associated with caves, springs, and mountains, most specifically the sacred mountain where he was believed to reside. Mount Tlaloc is very important in understanding how rituals surrounding this deity played out. His followers were one of the oldest and most universal in ancient Mexico.

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of the Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. According to legend, the various groups who were to become the Aztecs arrived from the north into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. The location of this valley and lake of destination is clear – it is the heart of modern Mexico City – but little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztec. There are different accounts of their origin. In the myth the ancestors of the Mexica/Aztec came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas to make the journey southward, hence their name "Azteca." Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, "the place of the seven caves", or at Tamoanchan.

Chalchiuhtlicue is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalchiuhtlicue is associated with fertility, and she is the patroness of childbirth. Chalchiuhtlicue was highly revered in Aztec culture at the time of the Spanish conquest, and she was an important deity figure in the Postclassic Aztec realm of central Mexico. Chalchiuhtlicue belongs to a larger group of Aztec rain gods, and she is closely related to another Aztec water god called Chalchiuhtlatonal.

Mictlan is the underworld of Aztec mythology. Most people who die would travel to Mictlan, although other possibilities exist. Mictlan consists of nine distinct levels.

Mictlāntēcutli or Mictlantecuhtli, in Aztec mythology, is a god of the dead and the king of Mictlan (Chicunauhmictlan), the lowest and northernmost section of the underworld. He is one of the principal gods of the Aztecs and is the most prominent of several gods and goddesses of death and the underworld. The worship of Mictlantecuhtli sometimes involved ritual cannibalism, with human flesh being consumed in and around the temple. Other names given to Mictlantecuhtli include Ixpuztec, Nextepehua, and Tzontemoc.

In Aztec mythology, Tonacatecuhtli was a creator and fertility god, worshipped for peopling the earth and making it fruitful. Most Colonial-era manuscripts equate him with Ōmetēcuhtli. His consort was Tonacacihuatl.

Tlaltecuhtli is a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican deity worshipped primarily by the Mexica (Aztec) people. Sometimes referred to as the "earth monster," Tlaltecuhtli's dismembered body was the basis for the world in the Aztec creation story of the fifth and final cosmos. In carvings, Tlaltecuhtli is often depicted as an anthropomorphic being with splayed arms and legs. Considered the source of all living things, he had to be kept sated by human sacrifices which would ensure the continued order of the world.

Tamoanchan is a mythical location of origin known to the Mesoamerican cultures of the central Mexican region in the Late Postclassic period. In the mythological traditions and creation accounts of Late Postclassic peoples such as the Aztec, Tamoanchan was conceived as a paradise where the gods created the first of the present human race out of sacrificed blood and ground human bones which had been stolen from the Underworld of Mictlan.

In creation myths, the term "Five Suns" refers to the belief of certain Nahua cultures and Aztec peoples that the world has gone through five distinct cycles of creation and destruction, with the current era being the fifth. It is primarily derived from a combination of myths, cosmologies, and eschatological beliefs that were originally held by pre-Columbian peoples in the Mesoamerican region, including central Mexico, and it is part of a larger mythology of Fifth World or Fifth Sun beliefs.

The Tzotzil are an indigenous Maya people of the central highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. As of 2000, they numbered about 298,000. The municipalities with the largest Tzotzil population are Chamula (48,500), San Cristóbal de las Casas (30,700), and Zinacantán (24,300), in the Mexican state of Chiapas.

The Huichol or Wixárika are an indigenous people of Mexico and the United States living in the Sierra Madre Occidental range in the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Zacatecas, and Durango, They are best known to the larger world as the Huichol, although they refer to themselves as Wixáritari in their native Huichol language. The adjectival form of Wixáritari and name for their own language is Wixárika.

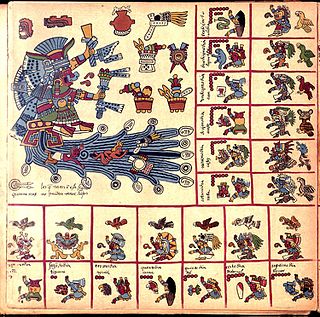

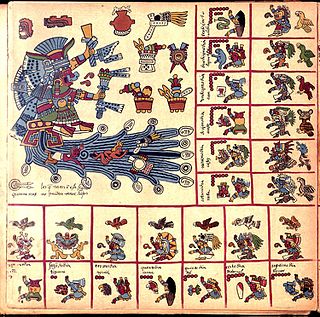

Snakes are a common occurrence in myths for a multitude of cultures. The Hopi people of North America viewed snakes as symbols of healing, transformation, and fertility. In other cultures snakes symbolized the umbilical cord, joining all humans to Mother Earth. The Great Goddess often had snakes as her familiars—sometimes twining around her sacred staff, as in ancient Crete—and they were worshipped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration. Although not entirely a snake, the plumed serpent, Quetzalcoatl, in Mesoamerican culture, particularly Mayan and Aztec, held a multitude of roles as a deity. He was viewed as a twin entity which embodied that of god and man and equally man and serpent, yet was closely associated with fertility. In ancient Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl was the son of the fertility earth goddess, Cihuacoatl, and cloud serpent and hunting god, Maxicoat. His roles took the form of everything from bringer of morning winds and bright daylight for healthy crops, to a sea god capable of bringing on great floods. As shown in the images there are images of the sky serpent with its tail in its mouth, it is believed to be a reverence to the sun, for which Quetzalcoatl was also closely linked.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

Chacala is a beach town set in small cove on the Pacific coast of Mexico in the State of Nayarit. It is located near pueblo Las Varas, about 100 kilometers (62 mi) north of Puerto Vallarta, and is part of the coastline known as the Riviera Nayarita. The name means "where there are shrimp" in Náhuatl. The population consists of approximately 300 full-time residents but can swell to over 1000 during Mexico's most popular vacation periods, such as Semana Santa and Christmas. Chacala is known for its physical beauty and unhurried lifestyle.

Tonalli plays a multiplicity of roles; acting as a day sign, body part, and a symbol of the sun's warmth. Ancient Nahua people believed that it was located in the hair and the fontanel area of one's skull, and that the tonalli provided the “vigor and energy for growth and development”. It often overlaps with the force of teyolía which was often considered both an animating force (soul) and the physical heart in various Mesoamerican cultures.

Plazuelas is a prehispanic archaeological site located just north of San Juan el Alto, some 2.7 kilometers (1.57 mi.) north of federal highway 90 (Pénjamo-Guadalajara), and about 11 kilometers (6.8 mi.) west of the city of Pénjamo in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. The site is open to the public; it is dominated by a large, rectangular plaza with several pyramidal structures and platforms, along with a massive ball court. To the north of the structures is a field of boulders with thousands of glyphs carved into them.

Mesoamerican religion is a group of indigenous religions of Mesoamerica that were prevalent in the pre-Columbian era. Two of the most widely known examples of Mesoamerican religion are the Aztec religion and the Mayan religion.

Cuahilama is a Hill and an archaeological site located south east of Santa Cruz Acalpixca, in the Cuahilama neighborhood, near the Xochimilco Archaeological Museum, in Mexico City. It was a ceremonial center, in the hill are prehispanic images engraved in basaltic rock.

El Teúl is an important archaeological Mesoamerican site located on a hill with the same name in the Teúl Municipality in the south of the Zacatecas State, Mexico, near the Jalisco State.

Huichol art broadly groups the most traditional and most recent innovations in the folk art and handcrafts produced by the Huichol people, who live in the states of Jalisco, Durango, Zacatecas and Nayarit in Mexico. The unifying factor of the work is the colorful decoration using symbols and designs which date back centuries. The most common and commercially successful products are "yarn paintings" and objects decorated with small commercially produced beads. Yarn paintings consist of commercial yarn pressed into boards coated with wax and resin and are derived from a ceremonial tablet called a neirika. The Huichol have a long history of beading, making the beads from clay, shells, corals, seeds and more and using them to make jewelry and to decorate bowls and other items. The "modern" beadwork usually consists of masks and wood sculptures covered in small, brightly colored commercial beads fastened with wax and resin.