In Aztec mythology, Xochiquetzal, also called Ichpochtli Classical Nahuatl: Ichpōchtli, meaning "maiden"), was a goddess associated with fertility, beauty, and love, serving as a protector of young mothers and a patroness of pregnancy, childbirth, and the crafts practiced by women such as weaving and embroidery. In pre-Hispanic Maya culture, a similar figure is Goddess I.

Chalchiuhtlicue is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalchiuhtlicue is associated with fertility, and she is the patroness of childbirth. Chalchiuhtlicue was highly revered in Aztec culture at the time of the Spanish conquest, and she was an important deity figure in the Postclassic Aztec realm of central Mexico. Chalchiuhtlicue belongs to a larger group of Aztec rain gods, and she is closely related to another Aztec water god called Chalchiuhtlatonal.

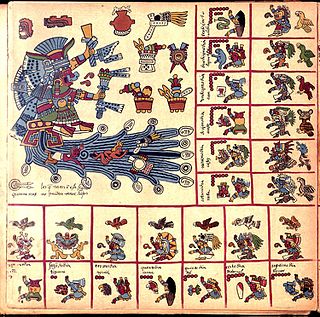

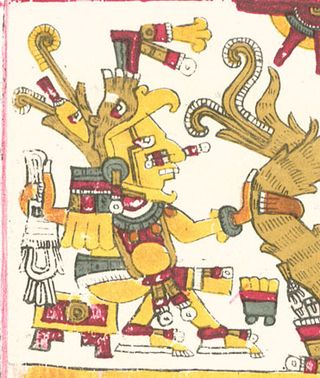

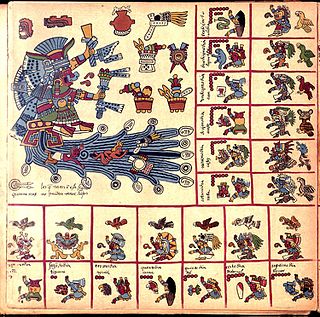

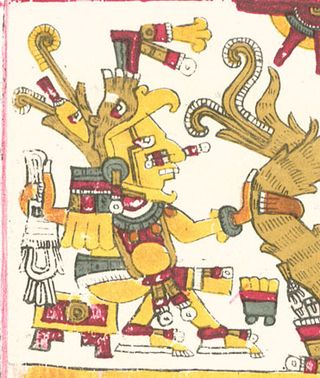

In Aztec mythology, Centeōtl is the maize deity. Cintli means "dried maize still on the cob" and teōtl means "deity". According to the Florentine Codex, Centeotl is the son of the earth goddess, Tlazolteotl and solar deity Piltzintecuhtli, the planet Mercury. He was born on the day-sign 1 Xochitl. Another myth claims him as the son of the goddess Xochiquetzal. The majority of evidence gathered on Centeotl suggests that he is usually portrayed as a young man, with yellow body colouration. Some specialists believe that Centeotl used to be the maize goddess Chicomecōātl. Centeotl was considered one of the most important deities of the Aztec era. There are many common features that are shown in depictions of Centeotl. For example, there often seems to be maize in his headdress. Another striking trait is the black line passing down his eyebrow, through his cheek and finishing at the bottom of his jaw line. These face markings are similarly and frequently used in the late post-classic depictions of the 'foliated' Maya maize god.

In comparative mythology, sky father is a term for a recurring concept in polytheistic religions of a sky god who is addressed as a "father", often the father of a pantheon and is often either a reigning or former King of the Gods. The concept of "sky father" may also be taken to include Sun gods with similar characteristics, such as Ra. The concept is complementary to an "earth mother".

The mythology of the ancient Basques largely did not survive the arrival of Christianity in the Basque Country between the 4th and 12th century AD. Most of what is known about elements of this original belief system is based on the analysis of legends, the study of place names and scant historical references to pagan rituals practised by the Basques.

Mother Nature is a personification of nature that focuses on the life-giving and nurturing aspects of nature by embodying it, in the form of a mother or mother goddess.

In Basque mythology, Basajaun is a huge, hairy hominid dwelling in the woods. They were thought to build megaliths, protect flocks of livestock, and teach skills such as agriculture and ironworking to humans.

Urtzi is an ancient Basque language term which is believed to either represent an old common noun for the sky, or to have been a name for a pre-Christian sky deity.

Tartaro, Tartalo, or Torto in Basque mythology, is an enormously strong one-eyed giant very similar to the Greek Cyclops that Odysseus faced in Homer's Odyssey. He is said to live in caves in the mountains and catches young people in order to eat them; in some accounts he eats sheep also.

Eki are the names of the Sun in the Basque language. In Basque mythology, Eki or Eguzki is seen as a child of Mother Earth to whom they return daily.

Ilargi, Ile or Ilazki was the Goddess of the Moon in Basque mythology.

Arantxa Urretabizkaia Bejarano is a contemporary Basque writer, screenwriter and actress. She was born in Donostia-San Sebastián, Guipúzcoa, País Vasco.

Andrés Ortiz-Osés was a Spanish philosopher. He was the founder of symbolic hermeneutics, a philosophical trend that gave a symbolic twist to north European hermeneutics.

Cantabrian mythology refers to the myths, teachings and legends of the Cantabri, a pre-Roman Celtic people of the north coastal region of Iberia (Spain). Over time, Cantabrian mythology was likely diluted by Celtic mythology and Roman mythology with some original meanings lost. Later, the ascendancy of Christendom absorbed or ended the pagan rites of Cantabrian, Celtic and Roman mythology leading to a syncretism. Some relics of Cantabrian mythology remain.

Juan Pérez de Lazarraga was a Basque writer, who was born and died in Larrea, Álava. Lazarraga, member of a family of the lower nobility originating in Oñati, was the Lord of Larrea.

Although the first instances of coherent Basque phrases and sentences go as far back as the San Millán glosses of around 950, the large-scale damage done by periods of great instability and warfare, such as the clan wars of the Middle Ages, the Carlist Wars and the Spanish Civil War, led to the scarcity of written material predating the 16th century.

Basque: Jose Miguel Barandiaran Aierbe, Spanish: José Miguel de Barandiarán y Ayerbe known as on Joxemiel Barandiaran and Aita Barandiaran, 'Father Barandiaran', was a Basque anthropologist, ethnographer, and priest.

Onésimo Díaz Hernández is a Spanish historian known for his publications regarding the history of Spain in the twentieth century.

Maritxu (María) Erlantz Guller, also known as the "sorgin ona" or white witch of Ulia, was a teacher, tarot reader and fortune teller who supposedly had paranormal powers.