Related Research Articles

The philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual data, in particular how they relate to beliefs about, or knowledge of, the world. Any explicit account of perception requires a commitment to one of a variety of ontological or metaphysical views. Philosophers distinguish internalist accounts, which assume that perceptions of objects, and knowledge or beliefs about them, are aspects of an individual's mind, and externalist accounts, which state that they constitute real aspects of the world external to the individual. The position of naïve realism—the 'everyday' impression of physical objects constituting what is perceived—is to some extent contradicted by the occurrence of perceptual illusions and hallucinations and the relativity of perceptual experience as well as certain insights in science. Realist conceptions include phenomenalism and direct and indirect realism. Anti-realist conceptions include idealism and skepticism. Recent philosophical work have expanded on the philosophical features of perception by going beyond the single paradigm of vision.

Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, which in turn result from physical or chemical stimulation of the sensory system. Vision involves light striking the retina of the eye; smell is mediated by odor molecules; and hearing involves pressure waves.

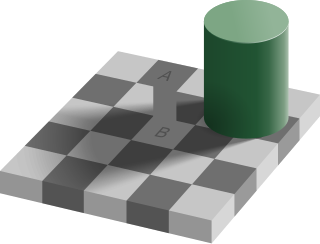

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

In visual perception, an optical illusion is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; their categorization is difficult because the underlying cause is often not clear but a classification proposed by Richard Gregory is useful as an orientation. According to that, there are three main classes: physical, physiological, and cognitive illusions, and in each class there are four kinds: Ambiguities, distortions, paradoxes, and fictions. A classical example for a physical distortion would be the apparent bending of a stick half immerged in water; an example for a physiological paradox is the motion aftereffect. An example for a physiological fiction is an afterimage. Three typical cognitive distortions are the Ponzo, Poggendorff, and Müller-Lyer illusion. Physical illusions are caused by the physical environment, e.g. by the optical properties of water. Physiological illusions arise in the eye or the visual pathway, e.g. from the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific receptor type. Cognitive visual illusions are the result of unconscious inferences and are perhaps those most widely known.

The Necker cube is an optical illusion that was first published as a Rhomboid in 1832 by Swiss crystallographer Louis Albert Necker. It is a simple wire-frame, two dimensional drawing of a cube with no visual cues as to its orientation, so it can be interpreted to have either the lower-left or the upper-right square as its front side.

Depth perception is the ability to perceive distance to objects in the world using the visual system and visual perception. It is a major factor in perceiving the world in three dimensions. Depth perception happens primarily due to stereopsis and accommodation of the eye.

In psychology, affordance is what the environment offers the individual. In design, affordance has a narrower meaning, it refers to possible actions that an actor can readily perceive.

Optical flow or optic flow is the pattern of apparent motion of objects, surfaces, and edges in a visual scene caused by the relative motion between an observer and a scene. Optical flow can also be defined as the distribution of apparent velocities of movement of brightness pattern in an image.

A sensorium (/sɛnˈsɔːrɪəm/) is the apparatus of an organism's perception considered as a whole, the "seat of sensation" where it experiences, perceives and interprets the environments within which it lives. The term originally entered English from the Late Latin in the mid-17th century, from the stem sens- ("sense"). In earlier use it referred, in a broader sense, to the brain as the mind's organ. In medical, psychological, and physiological discourse it has come to refer to the total character of the unique and changing sensory environments perceived by individuals. These include the sensation, perception, and interpretation of information about the world around us by using faculties of the mind such as senses, phenomenal and psychological perception, cognition, and intelligence.

Situated cognition is a theory that posits that knowing is inseparable from doing by arguing that all knowledge is situated in activity bound to social, cultural and physical contexts.

James Jerome Gibson was an American psychologist and is considered to be one of the most important contributors to the field of visual perception. Gibson challenged the idea that the nervous system actively constructs conscious visual perception, and instead promoted ecological psychology, in which the mind directly perceives environmental stimuli without additional cognitive construction or processing. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked him as the 88th most cited psychologist of the 20th century, tied with John Garcia, David Rumelhart, Louis Leon Thurstone, Margaret Floy Washburn, and Robert S. Woodworth.

Ecological psychology is the scientific study of perception-action from a direct realist approach. Ecological psychology is a school of psychology that follows much of the writings of Roger Barker and James J. Gibson. Those in the field of Ecological Psychology reject the mainstream explanations of perception laid out by cognitive psychology. The ecological psychology can be broken into a few sub categories: perception, action, and dynamical systems. As a clarification, many in this field would reject the separation of perception and action, stating that perception and action are inseparable. These perceptions are shaped by an individual's ability to engage with their emotional experiences in relation to the environment and reflect on and process these. This capacity for emotional engagement leads to action, collective processing, social capital, and pro environmental behaviour.

Multistable perception is a perceptual phenomenon in which an observer experiences an unpredictable sequence of spontaneous subjective changes. While usually associated with visual perception, multistable perception can also be experienced with auditory and olfactory percepts.

Subjective constancy or perceptual constancy is the perception of an object or quality as constant even though our sensation of the object changes. While the physical characteristics of an object may not change, in an attempt to deal with the external world, the human perceptual system has mechanisms that adjust to the stimulus.

A sensory cue is a statistic or signal that can be extracted from the sensory input by a perceiver, that indicates the state of some property of the world that the perceiver is interested in perceiving.

In psychology and cognitive neuroscience, pattern recognition describes a cognitive process that matches information from a stimulus with information retrieved from memory.

Scene statistics is a discipline within the field of perception. It is concerned with the statistical regularities related to scenes. It is based on the premise that a perceptual system is designed to interpret scenes.

Geometrical-optical illusions are visual illusions, also optical illusions, in which the geometrical properties of what is seen differ from those of the corresponding objects in the visual field.

The Gibsonian ecological theory of development is a theory of development that was created by American psychologist Eleanor J. Gibson during the 1960s and 1970s. Gibson emphasized the importance of environment and context in learning and, together with husband and fellow psychologist James J. Gibson, argued that perception was crucial as it allowed humans to adapt to their environments. Gibson stated that "children learn to detect information that specifies objects, events, and layouts in the world that they can use for their daily activities". Thus, humans learn out of necessity. Children are information "hunter–gatherers", gathering information in order to survive and navigate in the world.

Active perception is the selecting of behaviors to increase information from the flow of data those behaviors produce in a particular environment. In other words, to understand the world, we move around and explore it—sampling the world through our senses to construct an understanding (perception) of the environment on the basis of that behavior (action). Within the construct of active perception, interpretation of sensory data is inherently inseparable from the behaviors required to capture that data. Action and perception are tightly coupled. This has been developed most comprehensively with respect to vision where an agent changes position to improve the view of a specific object, or where an agent uses movement to perceive the environment.

References

- ↑ "Terms Used in Ecological Optics". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- 1 2 3 Noë, A. (2004). 3.9 Gibson, Affordences and the Ambient Optic Array. Action In Perception (pp. 103-106). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- 1 2 Gibson, J. J. (1986). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale (N.J.): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

- ↑ Reed, E. (1996). 4. Encountering the World: Toward An Ecological Psychology (pp. 48-49). New York: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Braisby, N., & Cellatly, A. (2012). 3.3 Flow in the ambient optic array. Cognitive Psychology (2nd ed., pp. 78-79). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Visual Perception Theory

- ↑ "The perceptual cycle". Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- ↑ Noë, A., & Thompson, E. (2002). 11: Selections from Vision. Vision and mind: Selected Readings in the Philosophy of Perception (pp. 264-265). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.