Charles of Orléans was Duke of Orléans from 1407, following the murder of his father, Louis I, Duke of Orléans. He was also Duke of Valois, Count of Beaumont-sur-Oise and of Blois, Lord of Coucy, and the inheritor of Asti in Italy via his mother Valentina Visconti.

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, was a French Prince of the Blood who supported the French Revolution, in the course of which he was executed.

MonsieurGaston, Duke of Orléans, was the third son of King Henry IV of France and his second wife, Marie de' Medici. As a son of the king, he was born a Fils de France. He later acquired the title Duke of Orléans, by which he was generally known during his adulthood. As the eldest surviving brother of King Louis XIII, he was known at court by the traditional honorific Monsieur.

Duke of Orléans was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives, or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King Philip VI for his younger son Philip, the title was recreated by King Charles VI for his younger brother Louis, who passed the title on to his son and then to his grandson, the latter becoming King Louis XII. The title was created and recreated six times in total, until 1661, when Louis XIV bestowed it upon his younger brother Philippe, who passed it on to his male descendants, who became known as the "Orléans branch" of the Bourbons.

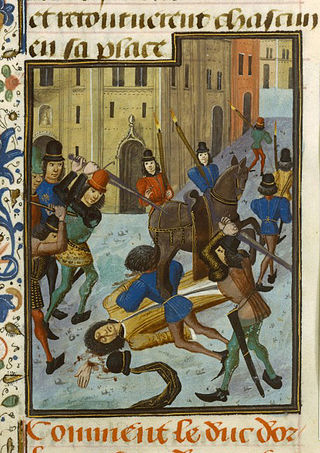

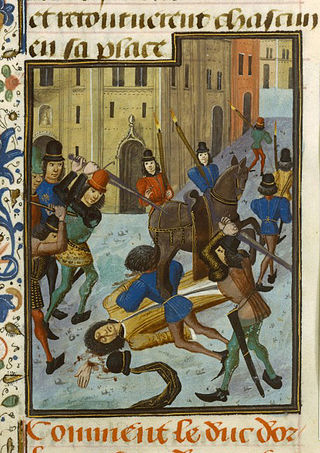

John I was a scion of the French royal family who ruled the Burgundian State from 1404 until his assassination in 1419. He played a key role in French national affairs during the early 15th century, particularly in the struggles to rule the country for the mentally ill King Charles VI, his cousin, and the Hundred Years' War with England. A rash, ruthless and unscrupulous politician, John murdered the King's brother, the Duke of Orléans, in an attempt to gain control of the government, which led to the eruption of the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War in France and in turn culminated in his own assassination in 1419.

Louis I of Orléans was Duke of Orléans from 1392 to his death. He was also Duke of Touraine (1386–1392), Count of Valois (1386?–1406) Blois (1397–1407), Angoulême (1404–1407), Périgord (1400–1407) and Soissons (1404–07).

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison is a 1975 book by French philosopher Michel Foucault. It is an analysis of the social and theoretical mechanisms behind the changes that occurred in Western penal systems during the modern age based on historical documents from France. Foucault argues that prison did not become the principal form of punishment just because of the humanitarian concerns of reformists. He traces the cultural shifts that led to the predominance of prison via the body and power. Prison is used by the "disciplines" – new technological powers that can also be found, according to Foucault, in places such as schools, hospitals, and military barracks.

Duke of Nemours was a title in the Peerage of France. The name refers to Nemours in the Île-de-France region of north-central France.

Charles Philippe Marie Louis d'Orléans is a member of the House of Orléans. He is the elder of two sons of Prince Michel d'Orléans and his former wife Béatrice Pasquier de Franclieu. His paternal grandfather was Prince Henri d'Orléans, the Orléanist pretender to the French throne. As such, Charles-Philippe takes the traditional royal rank of petit-fils de France with the style of Royal Highness.

Amable Guillaume Prosper Brugière, baron de Barante was a French statesman and historian. Associated with the center-left, he was described in France as the first man to call himself, "without any embarrassment or restriction, a Liberal."

The Anti-Sacrilege Act (1825–1830) was a French law against blasphemy and sacrilege passed in April 1825 under King Charles X. The death penalty provision of the law was never applied, but a man named François Bourquin was sentenced to perpetual forced labour for sacrilegial burglary; the law was later revoked at the beginning of the July Monarchy under King Louis-Philippe.

Jean Petit was a French theologian and professor in the University of Paris. He is known for his public defence of a political killing as tyrannicide.

Juvenile law pertains to those who are deemed to be below the age of majority, which varies by country and culture. Usually, minors are treated differently under the law. However, even minors may be prosecuted as adults.

Tanneguy III du Châtel was a Breton knight who fought in the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War and the Hundred Years' War. A member of the Armagnac party, he became a leading adviser of King Charles VII of France, and was one of the murderers of Duke John the Fearless of Burgundy in 1419.

The Bal des Ardents or the Bal des Sauvages, was a masquerade ball held on 28 January 1393 in Paris at which Charles VI of France performed in a dance with five members of the French nobility. Four of the dancers were killed in a fire caused by a torch brought in by Charles's brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans.

Marguerite of Lorraine, Duchess of Orléans, was the wife of Gaston, younger brother of Louis XIII of France. As Gaston had married her in secret in defiance of the King, Louis had their marriage nullified when it became known. On his deathbed, Louis permitted them to marry. After their remarriage, Marguerite and Gaston had five children. She was the stepmother of La Grande Mademoiselle.

The assassination of Louis I, Duke of Orléans took place on November 23, 1407 in Paris, France. The assassination occurred during the power struggles between two factions attempting to control the regency of France during the reign of Charles VI, who was seen as unfit to rule due to his mental illness. One faction was led by Louis, the king's younger brother, and Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, Charles' wife. They attempted to seize control of the country from the House of Burgundy after the death of the powerful Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold, in 1404.

Criminal justice in New France was integral to the successful establishment of a French colonial system in North America. New France was no stranger to criminal activity from its very roots. In 1608, shortly after the founding of Quebec, Samuel de Champlain executed Jean Duvel for allegedly leading a conspiracy against him. By 1636, the citizens of Québec began to be charged for crimes such as blasphemy, drunkenness and failing to attend Mass. As New France progressed, its legal institutions became more advanced. Promulgated across the France and the French Empire in 1670, the Criminal Ordinance of 1670 provided a foundation for New France's criminal procedures and punishments.

Louis d'Orléans Showing Off His Mistress is an 1825–1826 painting produced by the French artist Eugène Delacroix, now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. It shows Louis I, Duke of Orléans, his chamberlain Albert Le Flamenc and Mariette d'Enghien, who was both Le Flamenc's wife and the Duke's mistress. It draws on an episode recounted in both Prosper de Barante's Histoire des ducs de Bourgogne de la maison de Valois and Brantôme's Vie des dames galantes. It shows strong influence from Rubens and Titian as well as from Richard Parkes Bonington, a British artist with whom he actively swapped ideas and sketches between 1825 and 1828.

French criminal law is "the set of legal rules that govern the State's response to offenses and offenders". It is one of the branches of the juridical system of the French Republic. The field of criminal law is defined as a sector of French law, and is a combination of public and private law, insofar as it punishes private behavior on behalf of society as a whole. Its function is to define, categorize, prevent, and punish criminal offenses committed by a person, whether a natural person or a legal person. In this sense it is of a punitive nature, as opposed to civil law in France, which settles disputes between individuals, or administrative law which deals with issues between individuals and government.