Related Research Articles

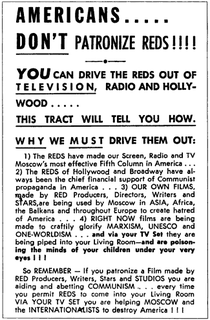

McCarthyism is the practice of making accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to communism and socialism. The term originally referred to the controversial practices and policies of U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin), and has its origins in the period in the United States known as the Second Red Scare, lasting from the late 1940s through the 1950s. It was characterized by heightened political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals, and a campaign spreading fear of alleged communist and socialist influence on American institutions and of espionage by Soviet agents. After the mid-1950s, McCarthyism began to decline, mainly due to Joseph McCarthy's gradual loss of public popularity and credibility after several of his accusations were found to be false, and sustained opposition from the U.S. Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren on human rights grounds. The Warren Court made a series of rulings on civil and political rights that overturned several McCarthyist laws and directives, and helped bring an end to McCarthyism.

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. It is often characterized as political propaganda. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which are referred to by this name. The First Red Scare, which occurred immediately after World War I, revolved around a perceived threat from the American labor movement, anarchist revolution, and political radicalism. The Second Red Scare, which occurred immediately after World War II, was preoccupied with the perception that national or foreign communists were infiltrating or subverting U.S. society and the federal government. The name refers to the red flag as a common symbol of communism.

The World Peace Council (WPC) is an international communist front organization that advocates universal disarmament, sovereignty and independence and peaceful co-existence, and campaigns against imperialism, weapons of mass destruction and all forms of discrimination. It was founded in 1950, emerging from the policy of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to promote peace campaigns around the world in order to oppose "warmongering" by the United States. Throughout the Cold War, it was largely funded and controlled by the Soviet Union, and refrained from criticizing or even defended the Soviet Union's involvement in numerous conflicts. These factors led to the decline of its influence over the peace movement in non-Communist countries. Its first president was the French physicist and activist Frédéric Joliot-Curie. It was based in Helsinki, Finland from 1968 to 1999, and since in Athens, Greece.

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties, and the National Negro Congress, serving as a defense organization. Beginning about 1948, it became involved in representing African Americans sentenced to death and other highly prominent cases, in part to highlight racial injustice in the United States. After Rosa Lee Ingram and her two teenage sons were sentenced in Georgia, the CRC conducted a national appeals campaign on their behalf, their first for African Americans.

Alice Prentice Barrows was a secretary of Dr. William A. Wirt, who headed the U.S. Office of Education in the early days of the New Deal of President Franklin Roosevelt. Barrows had been a member of the Communist party since 1919, the same year she began working for the Office of Education. During World War II Barrows was the executive secretary of the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship.

The Subversive Activities Control Board (SACB) was a United States government committee to investigate Communist infiltration of American society during the 1950s Red Scare. It was the subject of a landmark United States Supreme Court decision of the Warren Court, Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Control Board, 351 U.S. 115 (1956), that would lead to later decisions that rendered the Board powerless.

The "lavender scare" was a moral panic during the mid-20th century about homosexual people in the United States government and their mass dismissal from government service. It contributed to and paralleled the anti-communist campaign known as McCarthyism and the Second Red Scare. Gay men and lesbians were said to be national security risks and communist sympathizers, which led to the call to remove them from state employment. It was thought that gay people were more susceptible to being manipulated, which could pose a threat to the country.

The Russian Soviet Government Bureau (1919-1921), sometimes known as the "Soviet Bureau," was an unofficial diplomatic organization established by the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in the United States during the Russian Civil War. The Soviet Bureau primarily functioned as a trade and information agency of the Soviet government. Suspected of engaging in political subversion, the Soviet Bureau was raided by law enforcement authorities at the behest of the Lusk Committee of the New York State legislature in 1919. The Bureau was terminated early in 1921.

The Overman Committee was a special subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary chaired by North Carolina Democrat Lee Slater Overman. Between September 1918 and June 1919, it investigated German and Bolshevik elements in the United States. It was an early forerunner of the better known House Un-American Activities Committee, and represented the first congressional committee investigation of communism.

During the Cold War (1947–1991), when the Soviet Union and the United States were engaged in an arms race, the Soviet Union promoted its foreign policy through the World Peace Council and other front organizations. Some writers have claimed that it also influenced non-aligned peace groups in the West, although the CIA and MI5 have doubted the extent of Soviet influence.

The Soviet Peace Committee was a state-sponsored organization responsible for coordinating peace movements active in the Soviet Union. It was founded in 1949 and existed until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having either fascist or communist ties. It became a standing (permanent) committee in 1945, and from 1969 onwards it was known as the House Committee on Internal Security. When the House abolished the committee in 1975, its functions were transferred to the House Judiciary Committee.

During the ten decades since its establishment in 1919, the Communist Party USA produced or inspired a vast array of newspapers and magazines in the English language.

Guide to Subversive Organizations and Publications was a report published by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HCUA) during the Cold War. Originally published as a handbook in December 1948, it was revised and expanded in 1951, 1957, and 1961. The report listed organizations and publications cited as Communist fronts or "outright Communist enterprises" by federal, state, and municipal government agencies. In its original edition, 563 organizations and 190 publications were declared as subversive. Both private sector blacklisters and the FBI relied on the guide.

Herbert "Herb" Romerstein was an American ex-communist and historian who became a writer specializing in anticommunism and was appointed Director of the U.S. Information Agency’s Office to Counter Soviet Disinformation and Active Measures. As an author he is best known for his book The Venona Secrets.

A communist front is a political organization identified as a front organization under the effective control of a communist party, the Communist International or other communist organizations. They attracted politicized individuals who were not party members but who often followed the party line and were called fellow travellers.

The Workers World Party (WWP) is a revolutionary Marxist–Leninist political party in the United States founded in 1959 by a group led by Sam Marcy of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). Marcy and his followers split from the SWP in 1958 over a series of long-standing differences, among them their support for Henry A. Wallace's Progressive Party in 1948, the positive view they held of the Chinese Revolution led by Mao Zedong and their defense of the 1956 Soviet intervention in Hungary, all of which the SWP opposed.

Pacifism has manifested in the United States in a variety of forms, and in myriad contexts. In general, it exists in contrast to an acceptance of the necessity of war for national defense.

Counterattack was a weekly subscription-based, anti-communist, mimeographed newsletter, which ran from 1947 to 1955 and was published by a "private, independent organization" of the same name and started by three ex-Federal Bureau of Investigation agents.

References

- 1 2 Robbie Lieberman (2000). The Strangest Dream Communism, Anticommunism, and the U.S. Peace Movement, 1945-1963 (PB). Syracuse University Press (republished in 2010 by Information Age Publishing) (published 2010). pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-1-61735-054-2 . Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Martin J. Manning; Herbert Romerstein (2004). Historical dictionary of American propaganda. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-313-29605-5 . Retrieved 29 February 2012.

...Communist propaganda among prisoners of war in Korea, including front organizations, such as the American Peace Crusade...

- 1 2 Mike Forrest Keen (2004). Stalking sociologists: J. Edgar Hoover's FBI surveillance of American sociology. Transaction Publishers. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7658-0563-8 . Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 Lawrence S. Wittner (1997). Resisting the bomb: a history of the world nuclear disarmament movement, 1954-1970. Stanford University Press. pp. 324–25. ISBN 978-0-8047-2918-5 . Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- 1 2 Marian Mollin (12 September 2006). Radical pacifism in modern America: egalitarianism and protest. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8122-3952-2 . Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ Lieberman (2010) [2000], p. 101.

- 1 2 James Smallwood (31 March 2008). Reform, Red Scare, and Ruin. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 129–31. ISBN 978-1-4257-3202-8 . Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Lieberman (2010) [2000], p. 106.